Looking a little fragile

Market Morsel

The live sheep export trade from Australia has undergone a dramatic and prolonged decline, culminating in record-low volumes and a shrinking list of destination markets. Once a robust and highly profitable pillar of Australia’s livestock sector, the trade has become increasingly constrained by shifting market dynamics, policy interventions, and growing animal welfare concerns.

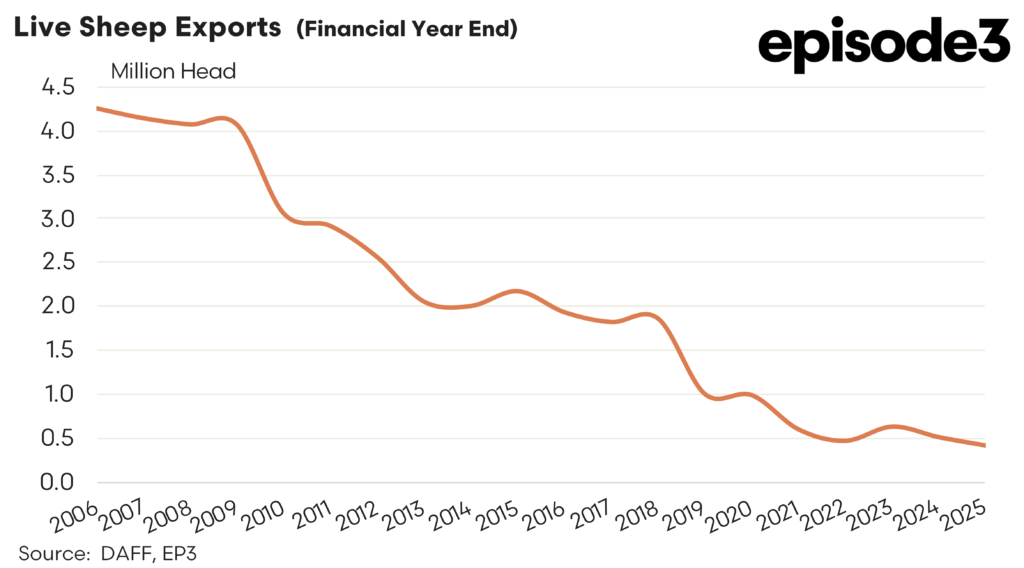

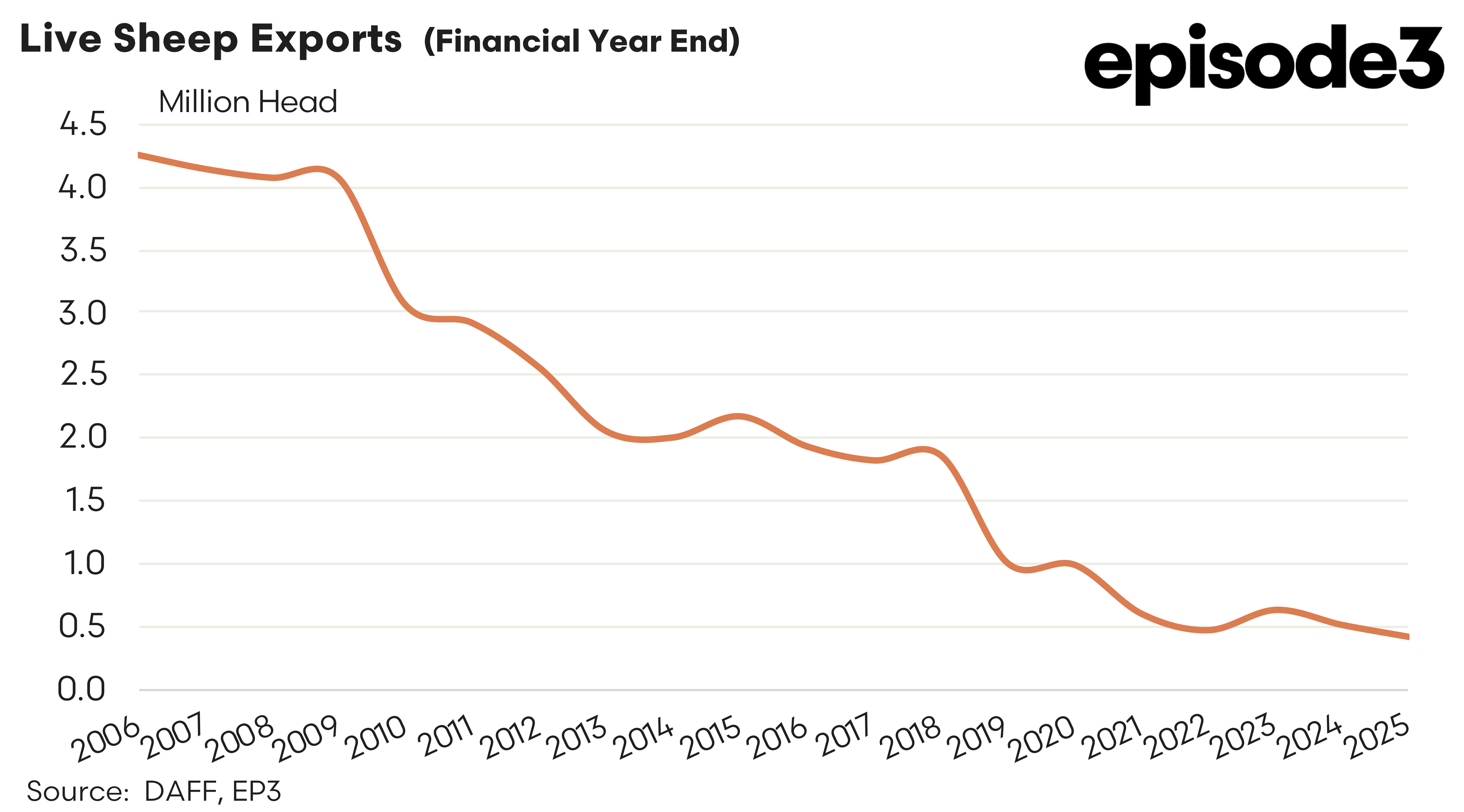

As of the 2024/25 financial year, live sheep exports have fallen to their lowest levels on record, with just 424,660 head shipped. This represents a staggering collapse from the 4.25 million head exported in 2005/06, and an even more dramatic decline when compared to the trade’s early 2000s peak. On a calendar year basis, the volume for 2024 also set a new low, with just 433,078 head exported. These figures highlight the accelerated unravelling of the trade, particularly over the last decade.

The tipping point for the modern phase of decline arguably began in 2018, following the Awassi Express incident. That episode, in which whistle blower footage exposed horrific conditions aboard a live export vessel, generated public outrage and brought the issue of animal welfare in the live trade into sharp national focus. The fallout from this event led to a range of regulatory changes and the introduction of a voluntary industry-led moratorium on shipping during the northern summer. While these measures were framed as reform efforts, and eventually became a mandated closure by the LNP government who were in charge at the time, they also had the effect of depressing volumes and disrupting the industry.

Despite these signals and the broader societal shift against live animal exports, the peak industry body representing exporters, ALEC, appeared to pursue a strategy almost entirely dependent on the prospect of a future change in government to reverse the policy direction. The Labor government’s commitment to phasing out live sheep exports by sea by mid-2028 was met not with a diversified or adaptive response, but with a politically focused campaign, centred around supporting pro live export trade candidates and leaning on grass roots groups like Keep the Sheep to help influence voter behaviours.

This approach has now been thoroughly defeated. The current government remains firm in its intent, has legislated the phase-out date, and appears unmoved by the industry’s campaign. With the failure of this strategy, ALEC appears to be left without a viable alternative, and the broader industry has lost valuable time that could have been used to plan for transition.

Beyond ALEC, serious questions must also be asked of other representative organisations such as Sheep Producers Australia and the National Farmers Federation. While ALEC’s role was more direct, these broader peak bodies appear to have been largely absent from any meaningful public leadership on the issue.

Anecdotal discussion with stakeholders suggests a common view that some of these representative organisations failed to proactively engage in transition planning, advocate for alternative market development, or provide support to affected producers. The inference is that this reflects a broader malaise in current agricultural advocacy where reactive politics has trumped constructive policy engagement. At a time when a united and forward-looking response was most needed, the sector seems to have clung to a singular, and ultimately futile, political hope.

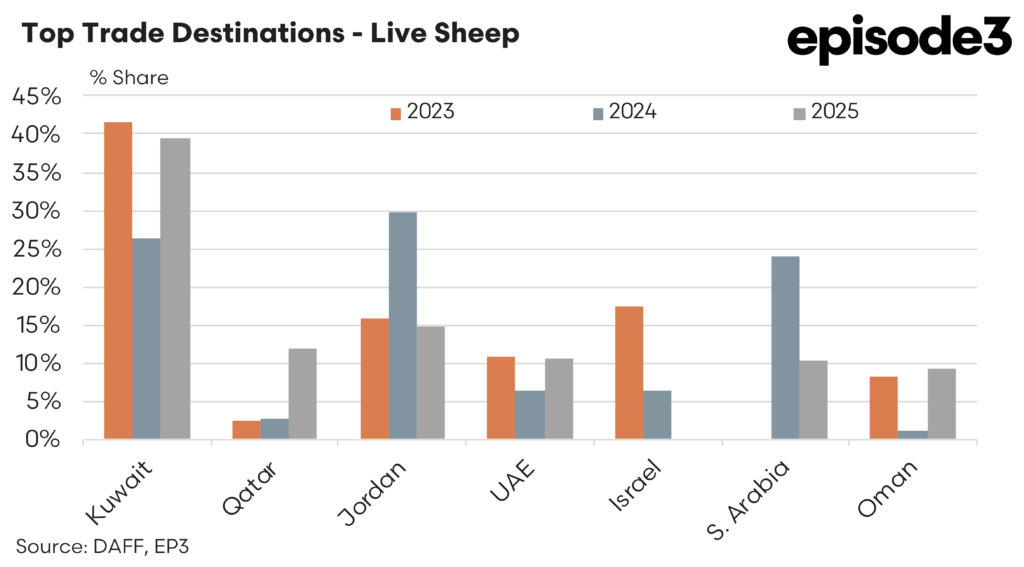

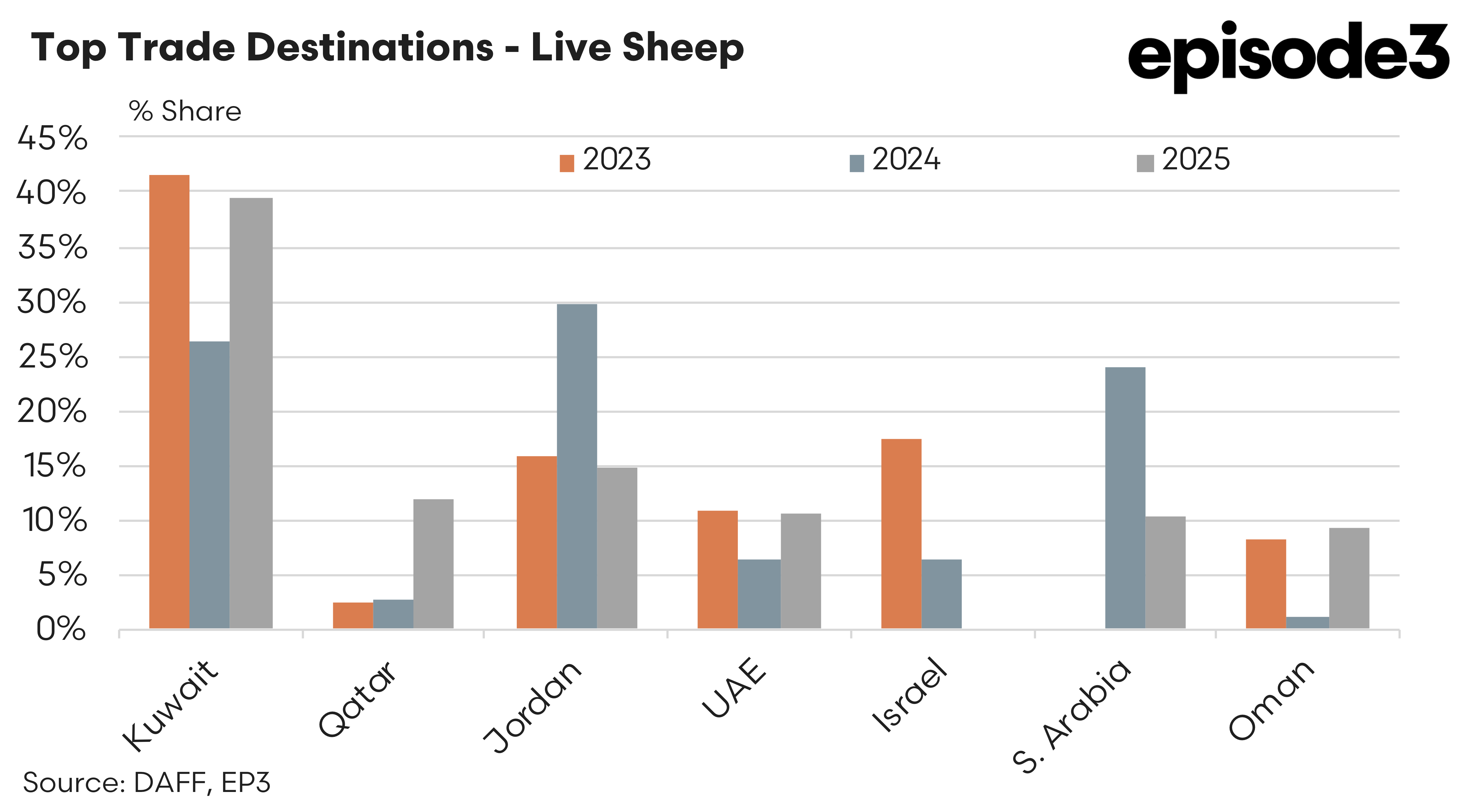

Compounding the problem has been the volatility and contraction in destination markets. Recent data shows that the market is dominated by a handful of countries, with Kuwait, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia accounting for the vast majority of trade presently. Even within this narrow field, market shares have fluctuated wildly in recent years.

Kuwait, the long-standing anchor of the trade, dropped from 42 percent share in 2023 to 26 percent in 2024, before rebounding to 40 percent in 2025. Jordan jumped from 16 percent in 2023 to 30 percent in 2024, only to fall back to 15 percent a year later. Saudi Arabia, which had no recorded trade in 2023 due to a decade long absence of sourcing from Australia, surged to 24 percent in 2024 and then declined to 10 percent in 2025. Israel, once a growth destination, completely withdrew from the trade by 2025, citing animal welfare concerns and growing domestic/nearby tensions causing shipping concerns.

These abrupt shifts in market share reflect both the fragility of demand and the transactional nature of trade agreements in the twilight of the industry. Rather than seeing sustained growth in new markets or stable long-term demand from existing ones, Australia’s live sheep sector has had to navigate a landscape of short-term purchases, abrupt halts, and unpredictable government interventions. With fewer markets and more concentrated exposure to a volatile region, the trade is not only smaller but increasingly precarious.

The collapse of Australia’s live sheep export trade has been shaped by both external pressures and internal failures. Regulatory and social forces have certainly played a major role, but the industry’s inability to respond with foresight and flexibility has hastened its downfall. By relying almost entirely on a change of government as its strategy, ALEC and its supporters ignored the structural headwinds and left the sector dangerously exposed. The failure of broader peak bodies to assert themselves and develop alternative strategies has only deepened the sense of missed opportunity. As the trade enters its final years, the sector faces not only the loss of a market but also the potential erosion of public trust in the institutions meant to represent it.