Why canola won’t hit A$1000 soon.

The Snapshot

The Detail

The canola market has been a great story of success for Australian agriculture. We are producing more, with larger areas going into the ground, but we have also experienced very strong pricing levels.

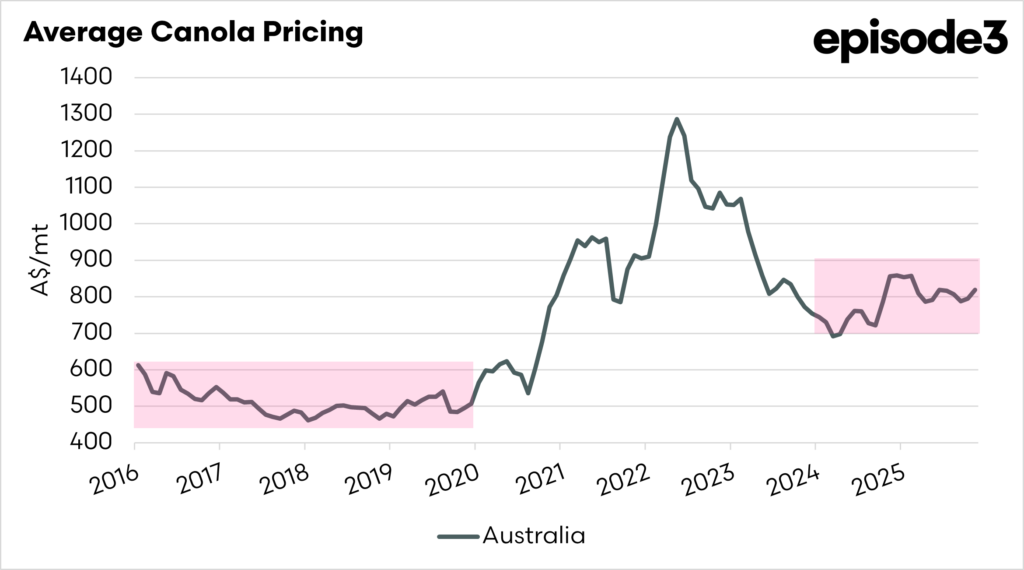

Everyone seems to fixate on the 2020-2023 period when canola prices rose well above A$1000/t, and the most common question we get about canola is: why aren’t we getting A$1000+ this year? We will take a look at that, but also why these ‘lower’ prices are still good.

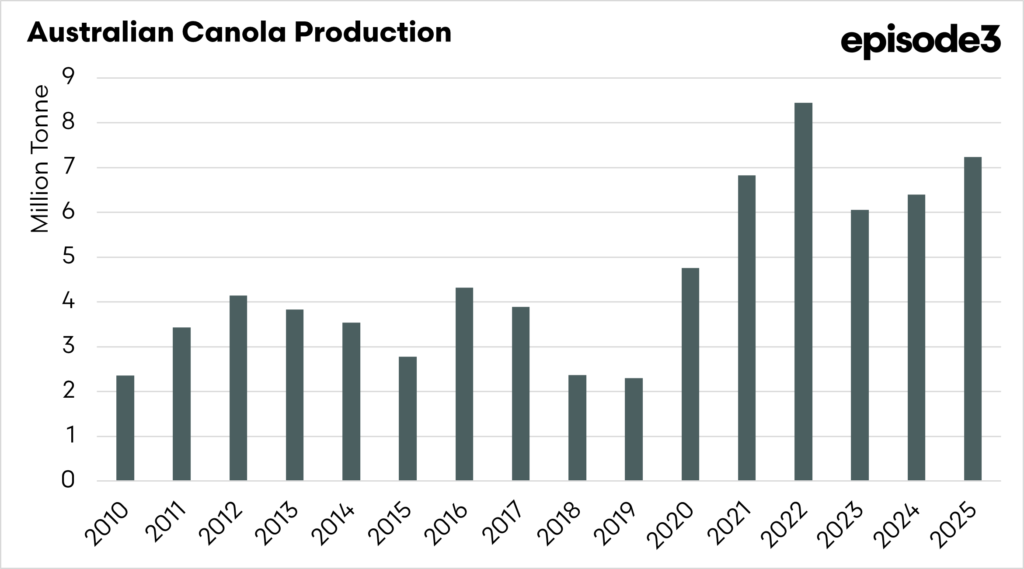

If we ignore the peak period, and look at the time 2016-2020, we can see that pricing tended to average A$534, with peaks around A$600. The period since the end of 2023 has averaged A$784; it’s well off the peak, but a strong price and a pricing banding that has stayed quite consistent.

There were multiple reasons for the pricing peaking a few years ago. Firstly, Canada, the world’s most important exporter of canola, has a terrible production year (more on that later). Secondly we also had the early stages of war in Ukraine, which added instability to a region responsible for the export of approximately 20% of the worlds canola. Thirdly, the cost of energy rose dramatically, which flows through to canola.

So the chances of canola prices above A$1000 are unlikely at the moment, so holding out for that might require holding your breath for a long time (and costing a lot in financing).

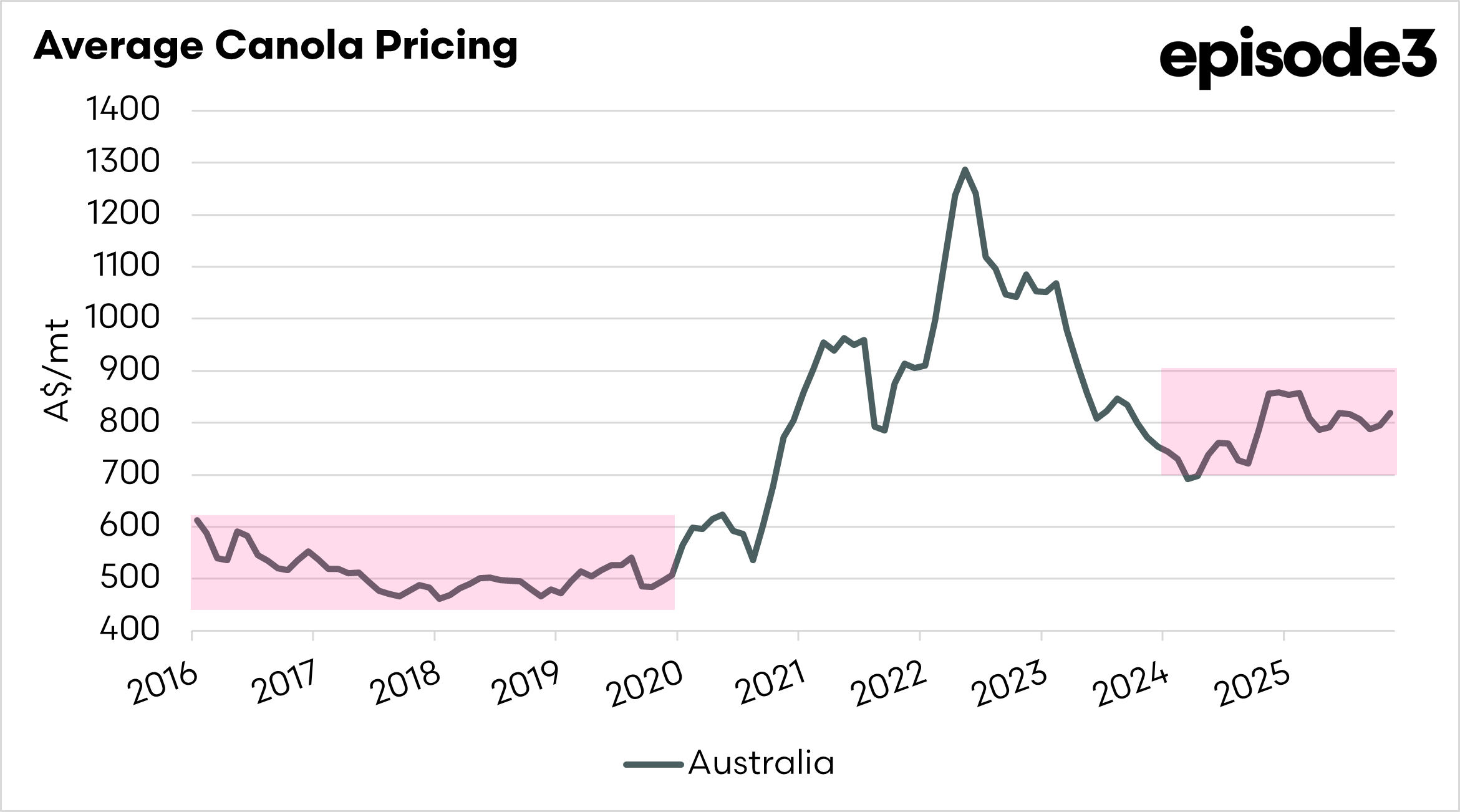

So let’s look at Canada. Last week, Statscan released their recent update on the Canadian canola production, and they are set to hit a record production of 21.8mmt. To put this in perspective, when we had those peaks, they had just come off a production of 14.2mmt.

This record production in Canada also comes at a time when they have constrained markets due to the inability to access China.

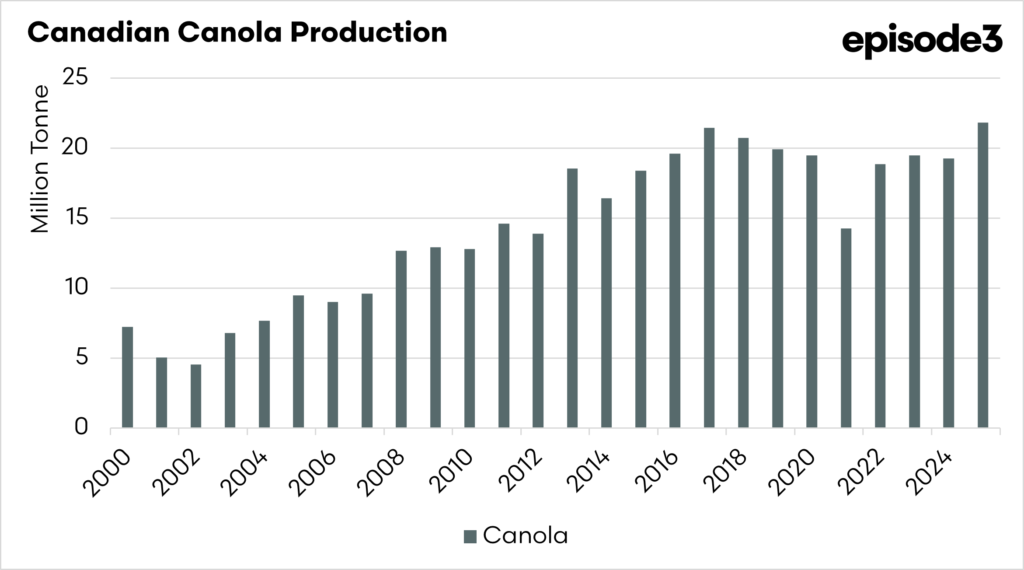

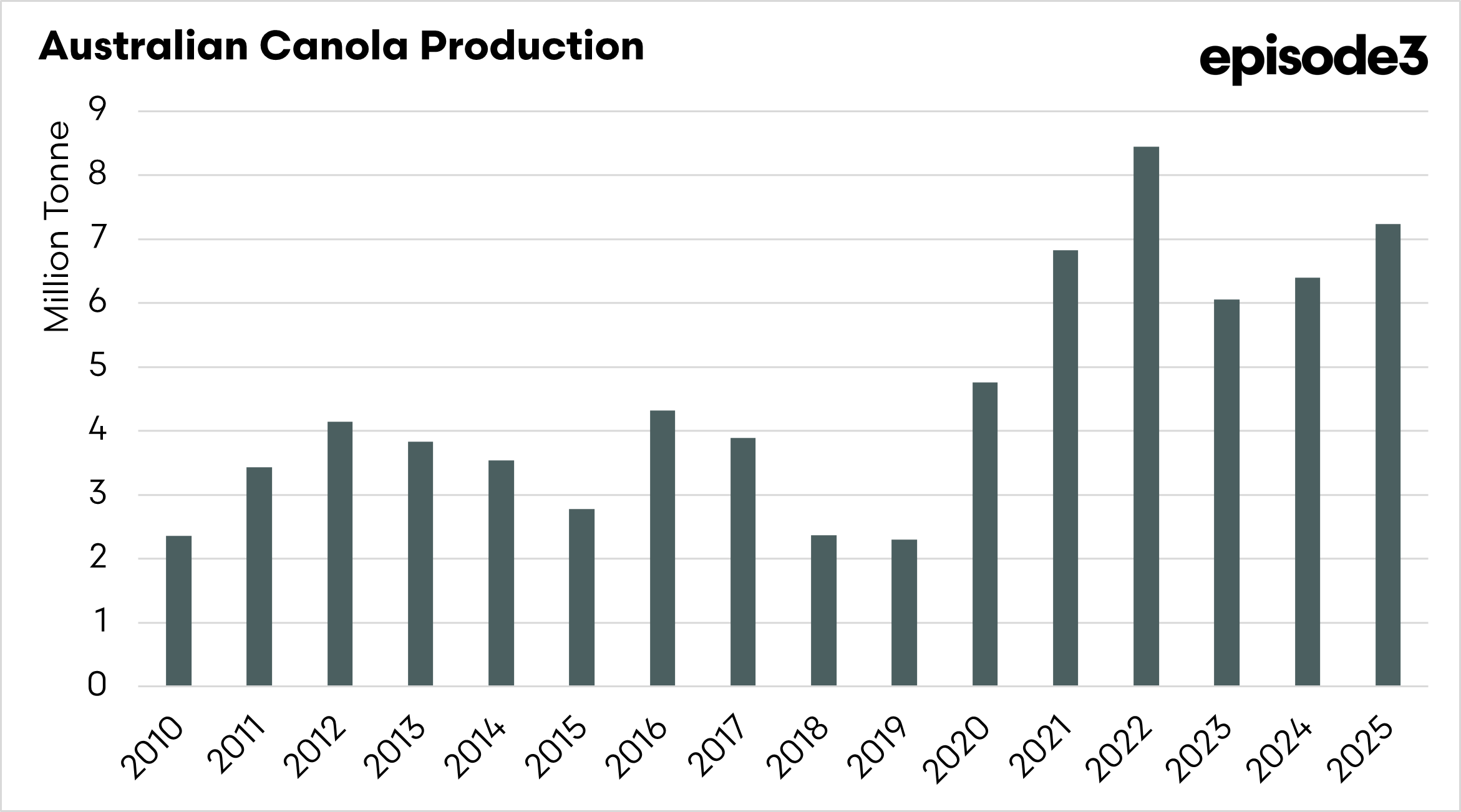

The same week Statscan released its figures, ABARES also released its end-of-year update.

This year, production is expected to achieve the silver medal, with the second-highest production on record, at 7.2mmt. This more than fulfils all of our domestic demand with plenty of seed for the export market.

This just adds more supply to the global market, alongside that huge Canadian crop.

You can listen to our podcast with abares below:

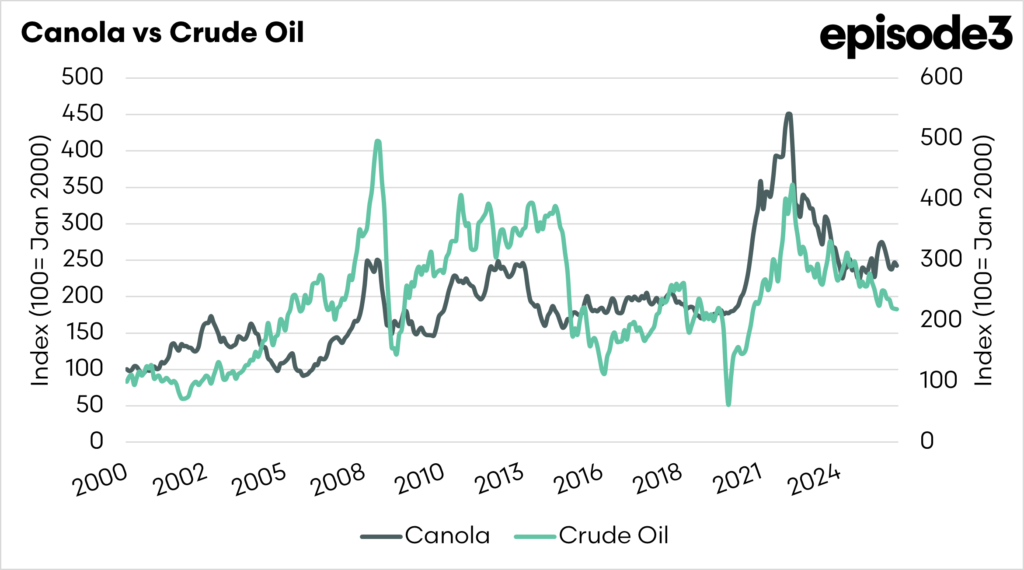

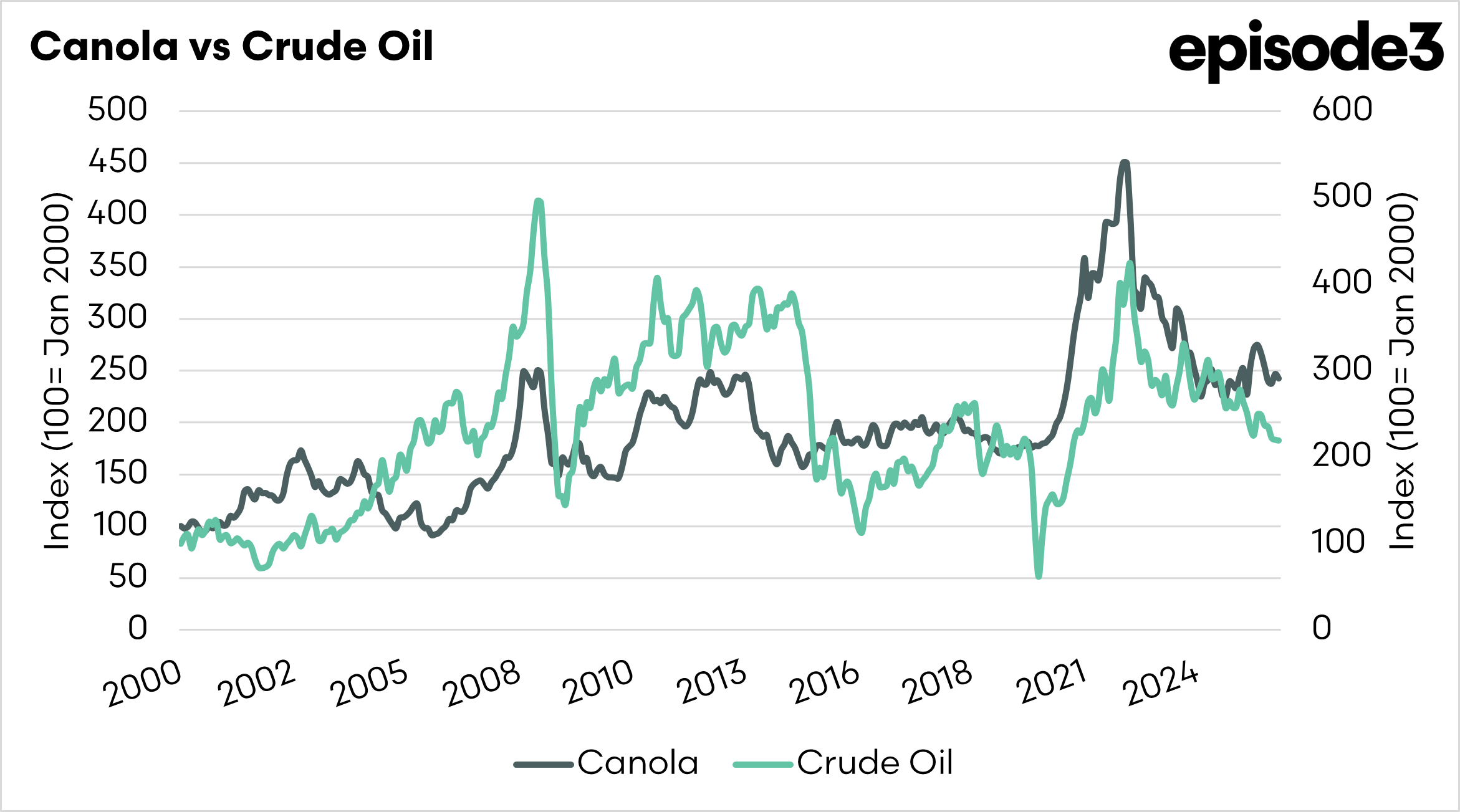

Let’s now look at energy and canola. We regularly track energy markets, because they have such an strong impact on our grain and oilseed markets.

Canola and other oilseeds tend to track the energy market because a large share of global demand for these crops is now tied to biofuel production, which links their pricing to the cost of crude oil and diesel. When energy prices rise, biodiesel becomes more competitive and profitable to produce, increasing demand for feedstocks such as canola, soy and palm oil. Conversely, when crude prices fall, biofuel margins tighten and demand for vegetable oils can soften, pulling oilseed prices lower.

The last few weeks have seen energy prices falling, as concerns mount of slowing global growth along with expectations of high surpluses in 2026.

So at a fundamental level, we have pretty good production in the world’s two most important exporters, the war in Ukraine is tentatively moving towards peace (won’t hold me breath on that), and energy prices are declining.

We have also seen an increase in farmer selling, which places pressure on pricing, which we can see in the next chart, which shows pricing levels falling under pressure, especially in the more domestically focused East Coast.