Grains/Oilseeds: Three Factors to watch in 2026.

Opportunities – if something goes wrong.

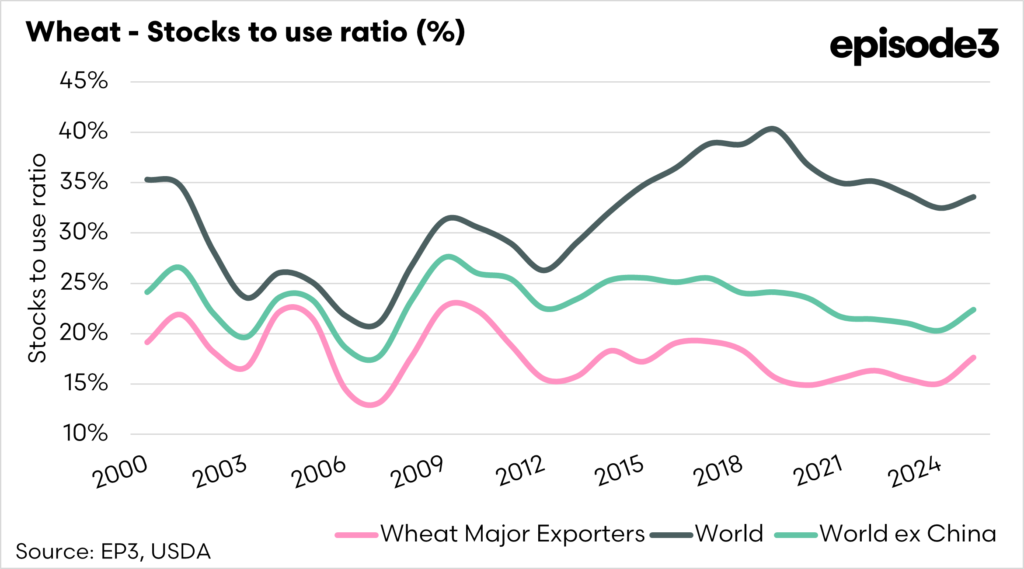

As the global wheat market moves into 2026, the stocks-to-use ratio remains one of the most important indicators of underlying price risk and market resilience. At first glance, headline global stock market indices suggest an adequately supplied system, particularly when compared with long-term averages. However, this apparent comfort conceals a more fragile underlying structure, in which the distribution and accessibility of stocks matter far more than the aggregate total.

China continues to hold an exceptionally large share of global wheat stocks, and its inclusion materially inflates the global stocks-to-use ratio. Once China is removed from the equation, the buffer available to the rest of the world tightens sharply. This is not a trivial adjustment. Chinese wheat stocks are largely policy-driven, domestically managed, and effectively insulated from global trade flows. In practical terms, they do little to cushion supply shocks elsewhere, meaning that the “rest of world” balance sheet is the one that actually matters for price formation.

The situation becomes even more acute when the focus narrows to the major exporting nations. While the exporters’ stocks-to-use ratio has lifted somewhat over the past year, it remains structurally lower and significantly more volatile than the global headline figure. These countries are the marginal suppliers to the world market and therefore the true price setters. Their tighter balance sheets mean that relatively modest disruptions can have outsized effects on prices, particularly during periods of heightened uncertainty.

This creates a market dynamic in which wheat is not globally scarce in aggregate, but tradable supply is sufficiently thin that confidence can be shaken quickly. Weather events across multiple major exporting regions, logistical disruptions, or geopolitical shocks would be sufficient to expose this vulnerability. The market does not need a catastrophic failure everywhere. It requires two or more key exporters to underperform simultaneously. Preferably, of course, not Australia.

In that sense, the global wheat market entering 2026 looks less like one constrained by outright shortage and more like one balanced on a narrow margin of error. Prices may appear subdued at times, but sensitivity remains high, and the potential for sharp repricing persists should disruptions occur on the supply side.

Energy markets and grain

Less than a week into 2026, global energy markets have already been shaken by significant geopolitical developments, including the capture and arrest of Venezuela’s president Nicolás Maduro and renewed civil unrest in Iran. These two countries rank among the largest holders of extractable crude oil reserves globally, giving them disproportionate strategic importance to energy markets.

While Venezuela’s oil resources are predominantly extra-heavy and lower quality, requiring significant upgrading and specialised refining capacity, they still represent a vast volume of supply. Iran, by contrast, holds large reserves of more conventional crude that are easier to bring to market. Despite differences in quality and commercial flexibility, disruption in either country can shift global energy price expectations.

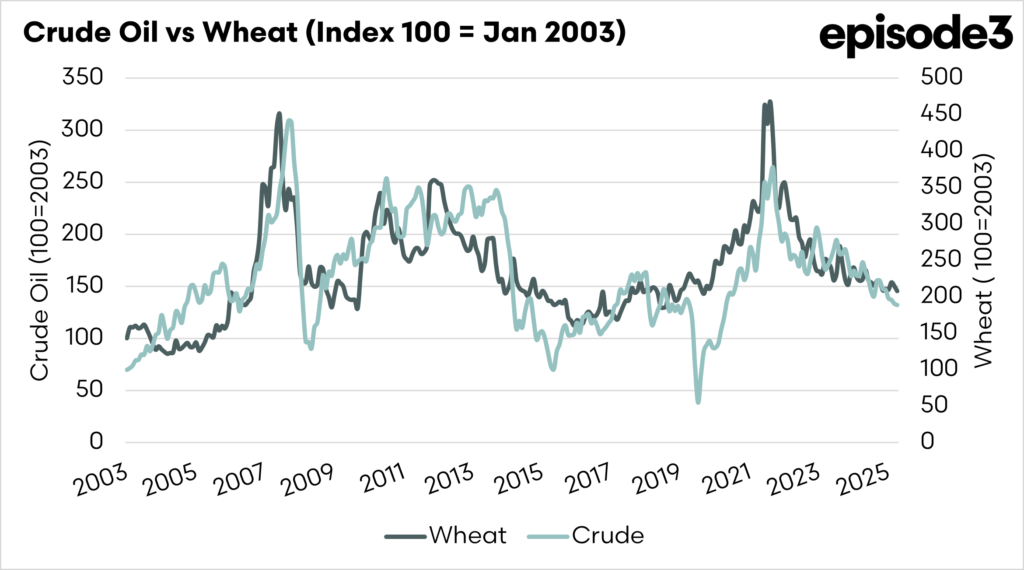

Energy prices matter for grain markets through multiple channels. Fuel costs influence freight, fertiliser production, and on-farm input expenses, while oil prices also shape broader macroeconomic sentiment and speculative flows into commodities. Historically, movements in energy markets have often coincided with increased volatility in grain prices, particularly during periods of geopolitical stress.

As 2026 unfolds, energy prices will continue to play a prominent role in shaping grain market dynamics. Whether prices rise due to supply disruptions or fall on expectations of resolution, the transmission into grain markets will remain an essential factor to monitor.

Peace in Ukraine

The war between Russia and Ukraine has also continued to defy early expectations. What was widely assumed to be a short-lived conflict has now entered its fourth year, with roots dating back to 2014. The human cost has been immense, and the geopolitical consequences continue to reverberate well beyond the region.

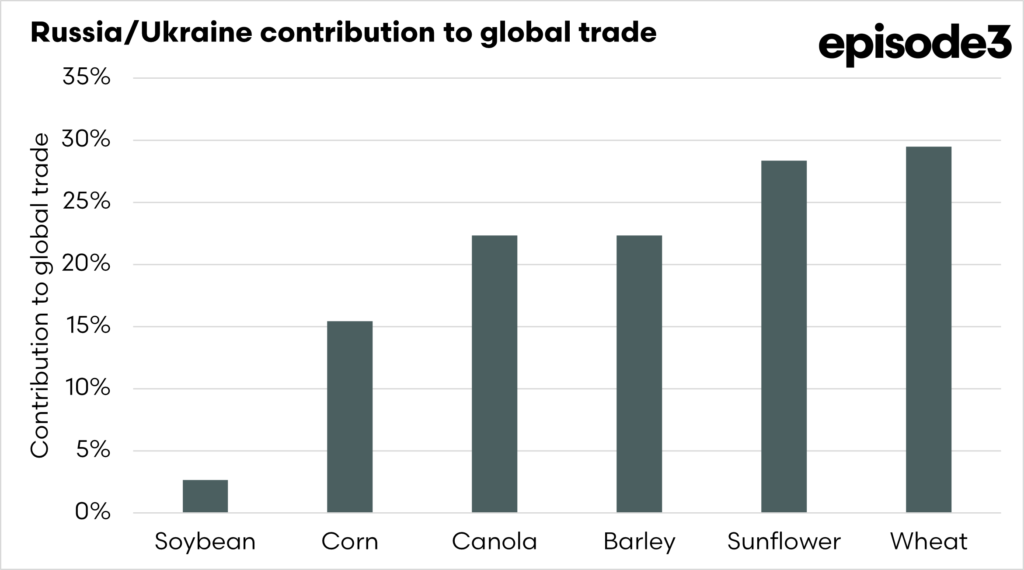

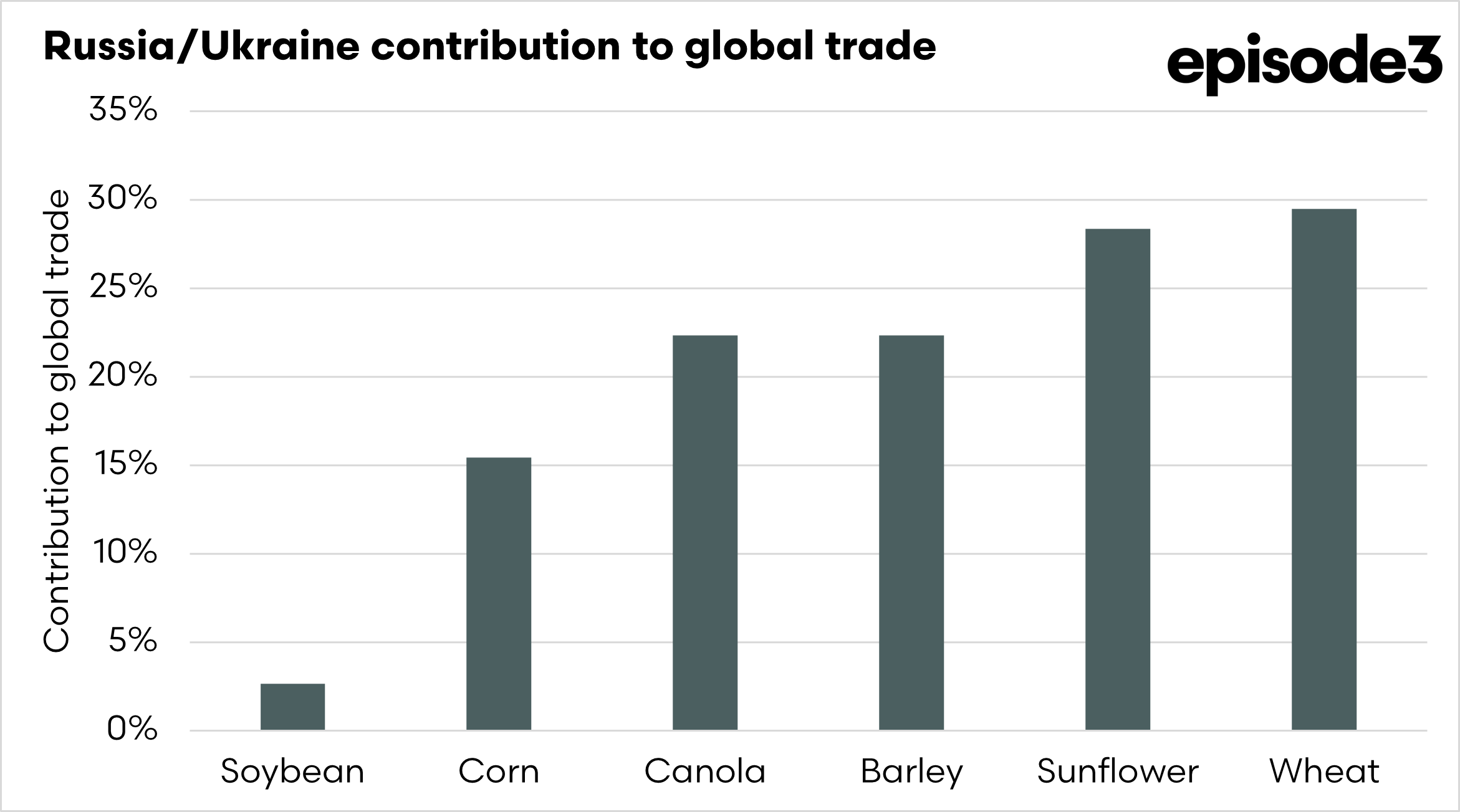

From a grain perspective, the importance of this conflict cannot be overstated. Russia and Ukraine together account for a significant share of global grain and oilseed trade. At the outset of the invasion, there were serious concerns that exports would be severely curtailed. While flows were disrupted in the early months, alternative logistics and trade arrangements were eventually established, allowing grain to move with fewer constraints than initially feared.

Remarkably, combined exports from Russia and Ukraine during the conflict years have, in some cases, exceeded pre-war levels. This resilience has helped stabilise global grain supply and prevent the extreme shortages that were once anticipated. However, it has also meant that a persistent risk premium has been embedded in prices, reflecting the ongoing uncertainty around shipping routes, infrastructure, and political stability.

At present, the prospect of peace appears closer than at any point over the past four years. Should a resolution emerge in the coming weeks, it would likely reduce the geopolitical risk premium currently priced into grain markets from the Black Sea region. A sustained easing of tensions could also place downward pressure on energy prices, reinforcing the link between geopolitics, oil, and agricultural commodities.

Taken together, these factors indicate that the global grain market will enter 2026 finely balanced. Stocks may look sufficient at first glance, but the system remains highly exposed to geopolitical and energy-driven shocks. In such an environment, price sensitivity remains elevated, and complacency is a luxury the market cannot afford.