The WA sheep exodus unleashing a grain surge.

The Snapshot

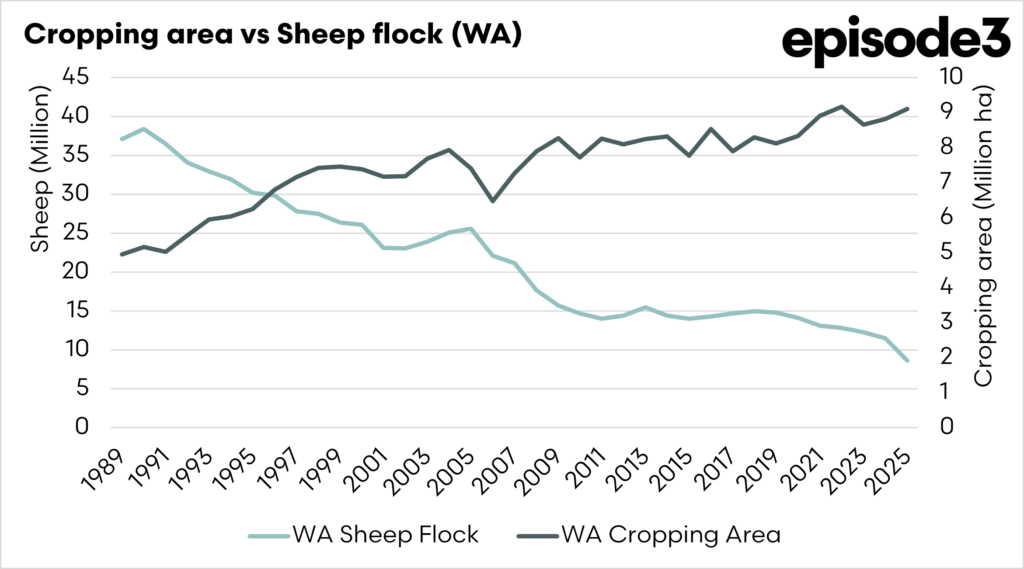

- Cropping area in Western Australia has expanded from around 5 million hectares in the late 1980s to more than 9 million hectares today, while the sheep flock has fallen from roughly 37 million head to an estimated 8.6 million in 2025.

- Live sheep exports have declined by close to 90 per cent from their late-2000s peak, and now account for only about 4 per cent of the state’s flock, limiting their influence on overall sheep numbers.

- The 2024–2025 flock reduction equates to approximately 2.9 million DSE, representing around 800,000 hectares of grazing capacity under a 3.5 DSE per hectare assumption.

- A hypothetical full conversion of that grazing capacity to cropping suggests between 700,000 and 1 million hectares could be added to grain production, equating to roughly 1.5–2.0 million tonnes of additional wheat in an average season.

- This additional production number is a very conservative estimate, and could be significantly higher.

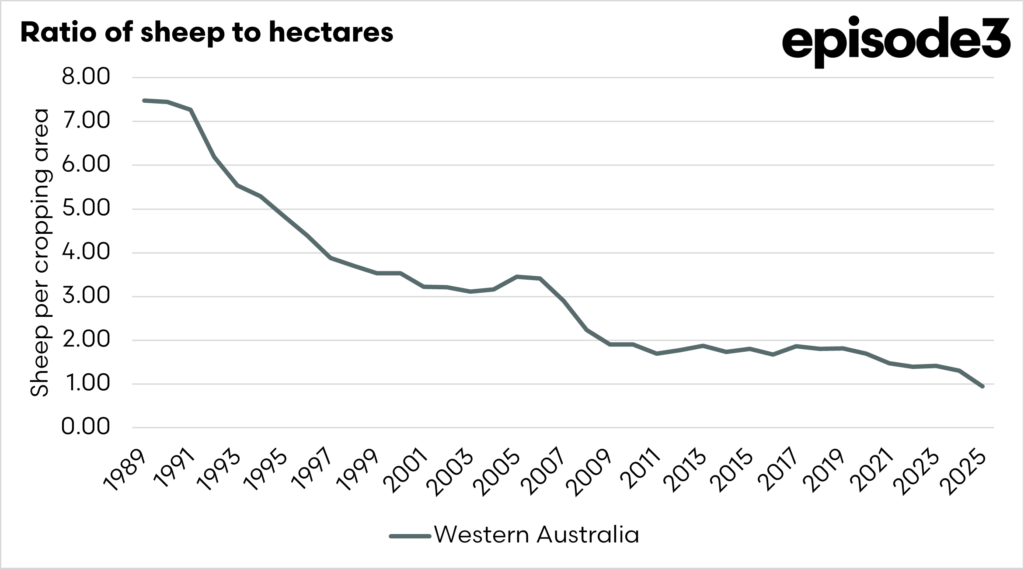

- As sheep numbers approach parity with cropped hectares, WA’s farming system continues shifting toward grain dominance, with further pressure on export logistics and infrastructure.

Western Australia’s broadacre farming system has been shifting toward cropping since the end of the reserve price scheme in the 90s, and the latest sheep and live export figures suggest that transition is entering another phase. Cropped area has expanded from roughly five million hectares in the late 1980s to more than nine million hectares today, while the state’s sheep flock has fallen from around 37 million head to an estimated 8.6 million in 2025. That change has fundamentally altered the structure of mixed farming across the wheatbelt. Sheep once dominated enterprise mix and land use, but cropping now drives the majority of revenue and investment decisions across the farming fraternity. The phase-out of live sheep export didn’t create this shift; it merely accelerated the trend and sped up land-use change.

Live sheep shipments from Western Australia exceeded four million head in the late 2000s and averaged more than two million through much of the 2010s. Since then, volumes have declined sharply. By 2024, exports were down to around 430,000 head and are estimated at roughly 330,000 head in 2025. This represents a fall of close to 90 per cent from peak levels. More importantly, live export now accounts for only a small share of the remaining flock. In the late 2000s, live export volumes represented roughly 10 to 15 per cent of Western Australia’s sheep population. Today, that share is closer to 4 per cent. The trade remains important for specific supply chains and regions, but it is no longer large enough to anchor the state’s overall flock size. The flock has already been adjusting downward for many years in response to relative enterprise returns, labour availability and the expansion of cropping.

To understand how further declines in sheep numbers could influence cropping area, the most practical approach is to translate the reduction in the flock into grazing demand using dry sheep equivalents. Assuming one sheep equals one DSE, the fall from around 11.5 million head in 2024 to about 8.6 million in 2025 implies a reduction of roughly 2.9 million DSE in a single year. That figure represents grazing pressure removed from the system rather than land area, but it provides a bridge to estimating how much land is no longer required to support sheep at previous stocking levels. Across Western Australia’s mixed wheatbelt, a reasonable whole-of-system carrying capacity is around 3 to 4 DSE per hectare. Using a central assumption of 3.5 DSE per hectare, the reduction in the flock equates to approximately 800,000 hectares of grazing capacity.

Treating this entire area as if it were converted into cropping provides a useful hypothetical upper bound. It does not suggest that all of this land will become cropping country in practice, but it illustrates the scale of land use change that is theoretically possible if the sheep flock continues to contract. Under a full conversion scenario, the decline in grazing demand implied by the 2025 flock estimate would be equivalent to between roughly 700,000 and one million hectares of additional cropping land, depending on the carrying capacity assumed. A central estimate of around 800,000 hectares sits comfortably within that range. Set against a cropping base already exceeding nine million hectares, this represents a substantial potential shift in the state’s land use balance.

Western Australia’s wheat yields provide a way to translate that hypothetical land area into grain production capacity. Over the past decade, state wheat yields have averaged a little above 2.2 tonnes per hectare, with weaker seasons closer to 1.5 tonnes and stronger seasons above 3 tonnes. Applying an average yield of around 2.3 tonnes per hectare to the hypothetical 800,000 hectares suggests that converting all grazing capacity to cropping could yield roughly 1.8 million tonnes of additional wheat production in an average season. In weaker seasons, the figure would be closer to 1.3 million tonnes, while in favourable seasons it could exceed 2.4 million tonnes. It is important to note that this average yield is representative of the state, but many areas moving out of sheep in the southern regions may have higher yields, but it is also important to take into account that yields have been trending higher in recent seasons.

The purpose of this 100 per cent conversion scenario is not to predict that all grazing land released by a smaller flock will become cropping. In reality, land use adjustments are more gradual and uneven. Some areas will remain in pasture but run at lower stocking rates. In lower rainfall districts and on lighter soils, cropping risk may limit expansion even if sheep numbers fall. Some producers will retain livestock as part of a mixed system to manage risk or for rotational benefits. However, in the central and southern wheatbelt, where cropping already dominates farm income, the removal of sheep from rotations increases the incentive to crop more frequently and across a larger share of the farm. The hypothetical conversion simply provides an upper bound for understanding how changes in the sheep flock translate into potential cropping capacity.

Western Australia is also approaching a structural tipping point in which the number of sheep in the state is roughly equal to the number of cropped hectares. Thirty years ago there were several sheep for every hectare of crop. Today, the ratio is close to 1:1. As the flock contracts further, the role of sheep in supporting pasture phases, labour allocation and risk management diminishes. This does not mean sheep disappear from the system, but it does mean that cropping increasingly determines the structure of farm businesses. Once sheep numbers fall below the level required to justify dedicated pasture phases across large areas of the wheatbelt, land use decisions become more closely aligned with cropping economics.

The grain production associated with that land is also not fixed. Yield improvements over time will influence how much grain flows from any additional cropped area. Western Australia’s wheat yields have trended higher over the long term as varieties, agronomy and seasonal management have improved. An expansion of this scale in cropping areas would also affect Western Australia’s grain export logistics. The state already produces a large exportable surplus and relies heavily on an efficient network of receival sites, storage facilities, rail lines and port terminals to move grain from paddock to vessel. Sustained increases in production capacity would place additional pressure on this infrastructure during strong seasons. While the system has demonstrated flexibility in handling large harvests, further growth in cropped area would reinforce the importance of ongoing investment in supply chain efficiency and export capacity. Any structural shift toward more cropping, therefore, has implications not only for farmers but also for the broader grain-handling and export network.

Taken together, the live export, flock and cropping data tell a consistent story. Western Australia’s agricultural system has been moving toward a cropping-dominant structure for many years. The decline in live sheep exports reflects that transition rather than initiating it. If the sheep flock continues to contract from current levels, the amount of land theoretically available for cropping will increase. A hypothetical full conversion of the grazing capacity associated with the 2025 flock decline suggests that between 700,000 and one million hectares could be in play, equivalent to roughly 1.5 to 2.0 million tonnes of additional wheat production capacity in an average season.

The direction is clear, and has been before the live export ban; the trend has just been sped up. Western Australia is increasingly a grain-focused production system, with sheep moving further towards being a niche industry.