Farm Aid: America’s FAFO Moment

American farmers voted overwhelmingly for the trade and anti-immigration policies of Trump; they are now finding that it is impacting their bottom line. American farmers have lost their biggest export market, China, during the current trade war. The American agricultural industry, which has been heavily assisted by illegal migrants, has now lost many of its workers.

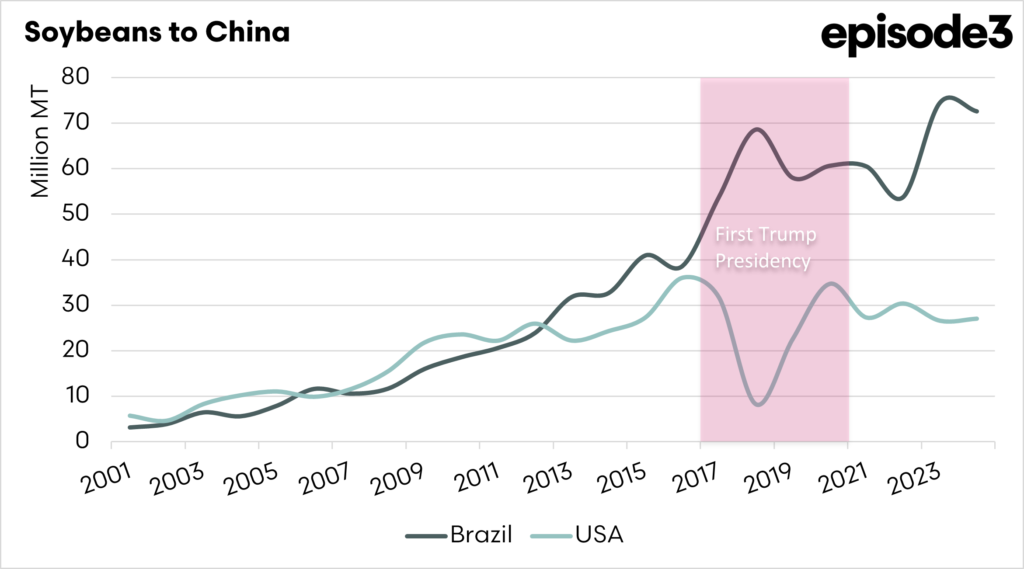

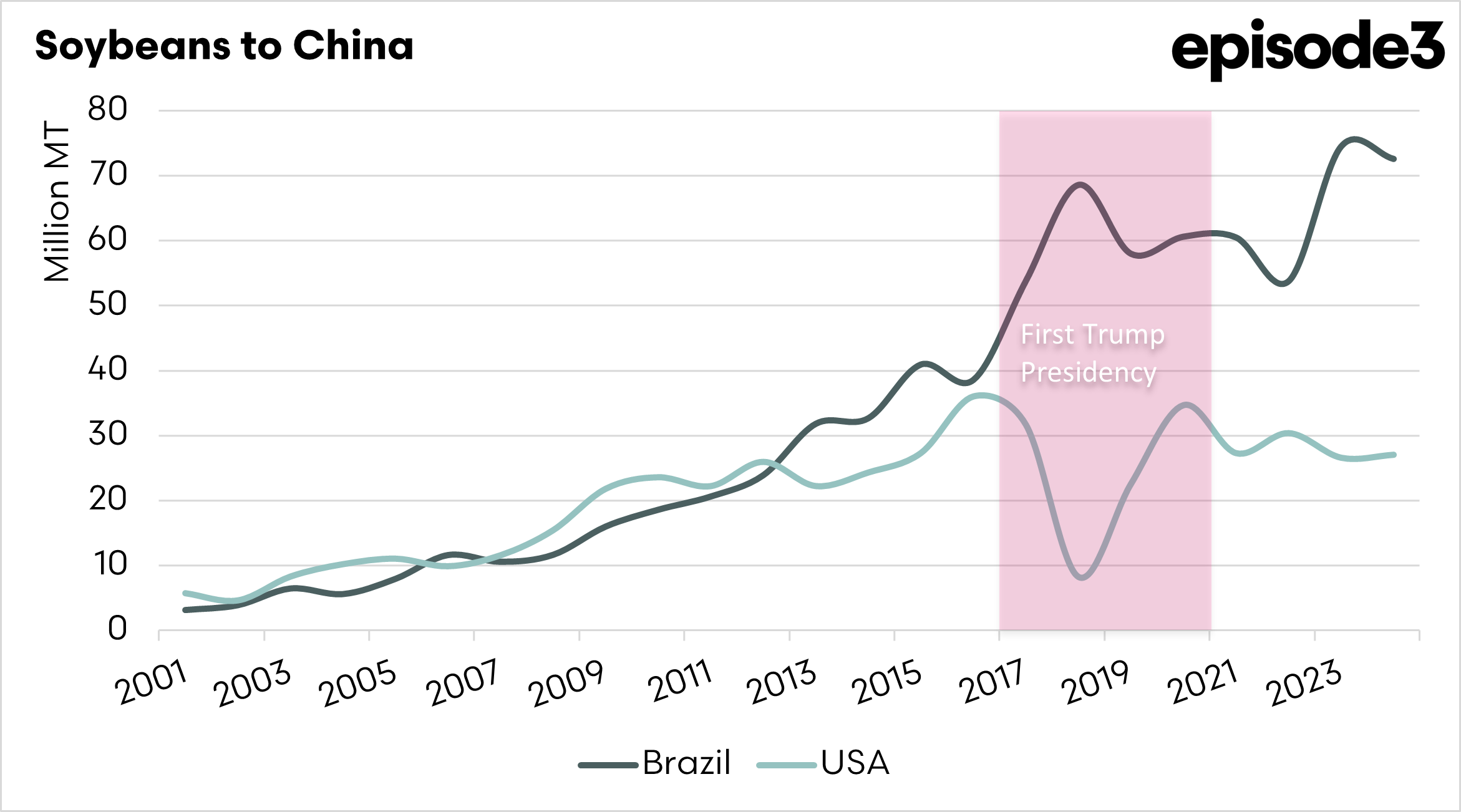

For decades, Chinese demand had underpinned the Midwest economy, taking roughly a third of US production. Then came the Trump Trade wars. The response by the US government will be to release billions of dollars in aid taxpayer-funded compensation for the losses created by its own policies.

Many of the same rural communities that voted enthusiastically for the Trump administration’s protectionist and anti-immigration platform have since discovered that policy choices have real-world costs. The “get tough on China” stance that played well at rallies effectively dismantled one of America’s most important trade relationships. China didn’t simply absorb the blow it pivoted fast, locking in long-term supply deals with Brazil and expanding its crushing and logistics capacity. The result is a trade shift that will possibly be permanent.

Tighter border controls and the crackdown on undocumented workers have made life harder for American farmers. Across the industry, farmers now struggle to find enough workers. The reality is that much of American agriculture relies on migrant labour a fact often ignored.

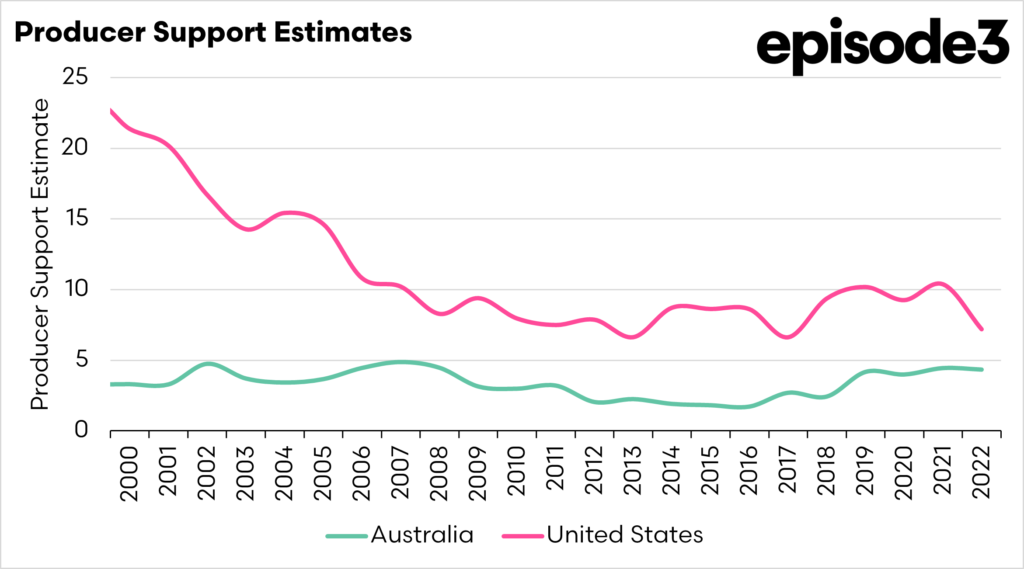

Faced with weaker demand and higher costs, Washington’s answer will be to open the chequebook. Billions in aid will be redistributed to farmers to offset the losses created by government policy. Strip away the rhetoric, and that is socialism in practice the state transferring public money to sustain private enterprise. It’s redistribution, not competition, that keeps the lights on. Taxpayer-funded intervention to shield an industry from the consequences of market forces and government policy.

The problem is that the challenges run deeper than lost trade. While grain and oilseed prices have come under pressure, the cost of farming has risen sharply. Machinery, fertiliser, fuel and insurance all cost more than they did a few years ago, leaving producers squeezed between lower prices and higher inputs. This cost–price squeeze is now the defining feature of modern agriculture. Even when yields are good, margins remain tight. Government support might ease the pressure, but it can’t erase it.

Futures markets reflect this dynamic clearly. When the government cushions producers from losses, it dulls the incentive to reduce output or diversify. Farmers keep planting soybeans even when demand is weak, sustaining oversupply and keeping prices capped. Subsidies stabilise incomes but can prolong market weakness. In the long run, that risks turning emergency support into dependency.

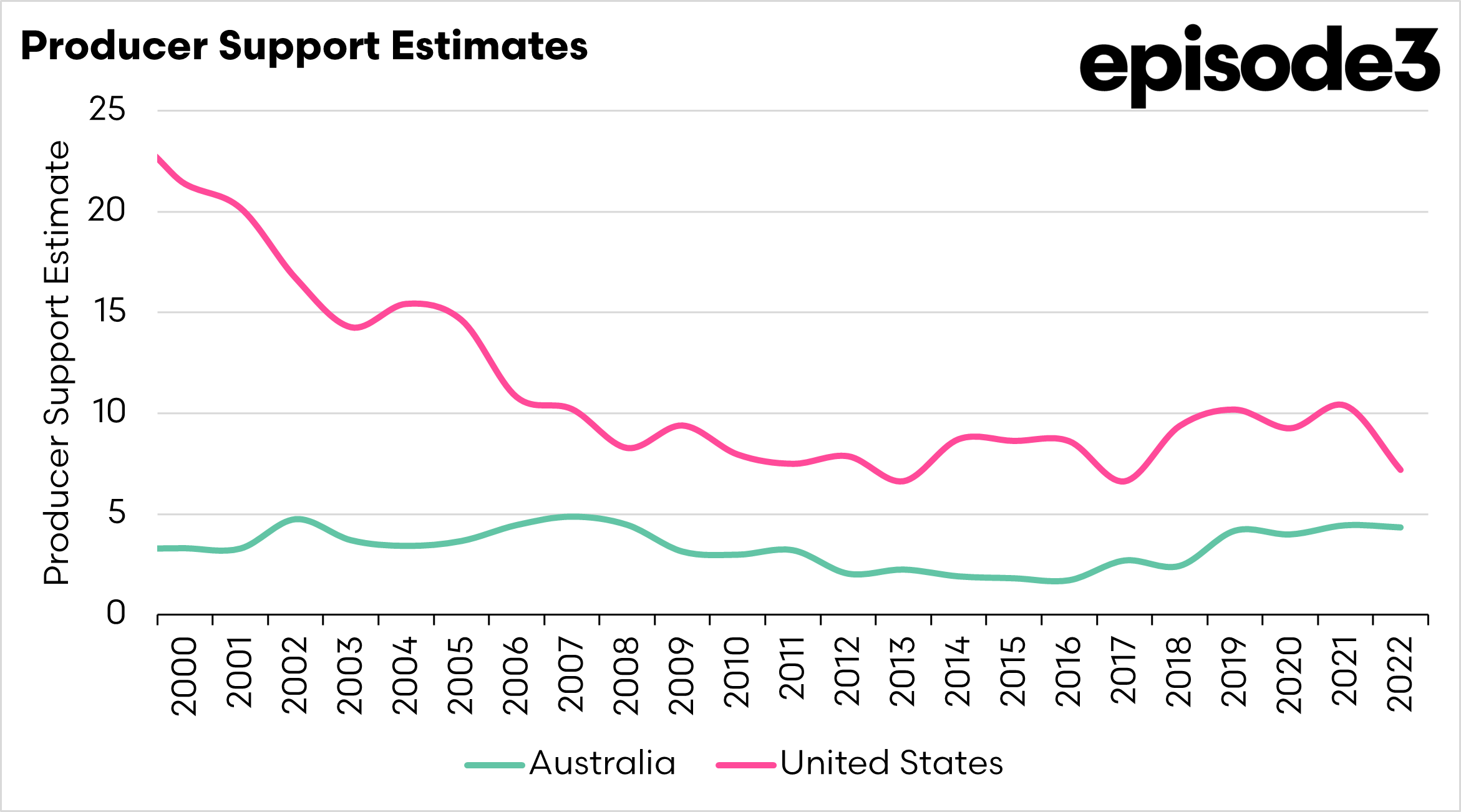

Australian farmers are already among the least subsidised in the world, whilst US farmers already receive a significant amount of income from subsidies. Australian farmers have gone it alone for most of the past few decades.

Many farmers supported policies aimed at protecting American jobs and industries, but those same policies have made them more reliant on government assistance. Trade retaliation hurt exports; immigration controls tightened labour supply; and now taxpayers are footing the bill to plug the gap. It’s not a failure of capitalism so much as a lesson in how interconnected markets really are and how quickly political rhetoric collides with economic reality.

None of this means support for farmers is wrong. Agriculture is strategic; food security matters, and the sector faces unique volatility from weather, global supply chains and geopolitics. There’s a legitimate case for safety nets when those forces collide. But pretending that trade wars and labour shortages come without a price is delusional. You can’t choke off demand and workers and expect supply chains to hum along unaffected.

This is the American farmers FAFO moment. Farmers are learning, painfully, that the global economy can’t be walled off or bullied into submission. Markets respond, competitors adapt, and once customers shift their supply lines, they rarely come back quickly. The lesson is clear: policy built on slogans has a habit of hitting hardest at those it was meant to protect.

So, yes, government aid may keep farms afloat for now. But it’s not independence; it’s insurance an expensive reminder that in agriculture, as in politics, actions have consequences. And this time, the bill for finding out comes straight from the public purse.

From a market perspective, the aid acts as both a safety net and a ceiling. When farmers know that the government will provide a safety net, it removes some of the production risk that normally constrains supply. Rather than cutting area or switching crops, they keep planting soybeans, confident that support will bridge any gap between cost and price. That prevents a deeper short-term slump in rural incomes but it also keeps more grain flowing into an already saturated market.

Futures markets see this clearly. Subsidy programs don’t usually spark rallies; if anything, they anchor prices lower by signalling that production will stay high despite weak demand. Traders read those payments as a form of artificial supply support a reason to discount the potential for natural correction. When this aid is finally announced, the market might react negatively to the news.

In the end, government support will prop up their farmers, but it has to be removed at some point, and that is when it really hurts. We have our own example in Australia with the removal of the wool price reserve scheme.