Foot and Mouth Disease – A personal and trade perspective.

The Snapshot

- Foot and Mouth disease is gaining a lot more traction in the press.

- This is due to the disease being detected in Indonesia.

- FMD has been detected in numerous countries in recent years, but we have a huge number of Australians heading to Indonesia on a monthly basis (avg 103k or 12% of travellers)

- ABARES estimated in 2013 that the cost would be $50bn for a full-blown outbreak. In all likelihood, this cost would be far higher in 2022.

- Exports of meat from the UK took a long time to recover after the 2001 outbreak.

- The Australian sheep and beef industry is reliant on exports, a closure of our export pathway would be disastrous.

- It doesn’t just impact animal welfare or the economy. An FMD outbreak would have long term social and psychological impacts on rural communities.

- EID tags at A$1.30 seem like cheap insurance.

The Detail

I want to start this piece by saying that I am not an expert in livestock diseases by any stretch of the imagination. However, I have a little bit of personal experience with foot and mouth disease (FMD).

During my teenage years, what feels like many moons ago, I lived in Dumfries and Galloway. The 2001 outbreak of FMD had a huge impact on our region and one that took a long time to recover from; I spoke about this experience recently on the ABC. In addition, I was lucky to be picked to conduct ‘real time training in FMD’ in Nepal through Wool Producers Australia.

My hometown was largely closed down during 2001, with soldiers on the streets, checkpoints at farm entrances and the popping sounds of animals being culled. I couldn’t visit a girl I was courting at the time. The summer of 2001 for a teenage boy was a sorry affair.

The smell of burning meat didn’t leave town for what felt like an entire summer. You get tired of that quickly.

Why the sudden concern?

Why are we so concerned with the infection in Indonesia? Well, firstly, it is relatively close to Australia.

Indonesia is close on a global scale, but it is still hundreds of kilometres from the mainland. In reality, it’s not going to float over the water. If it arrives from Indonesia, it will likely come via plane or boat.

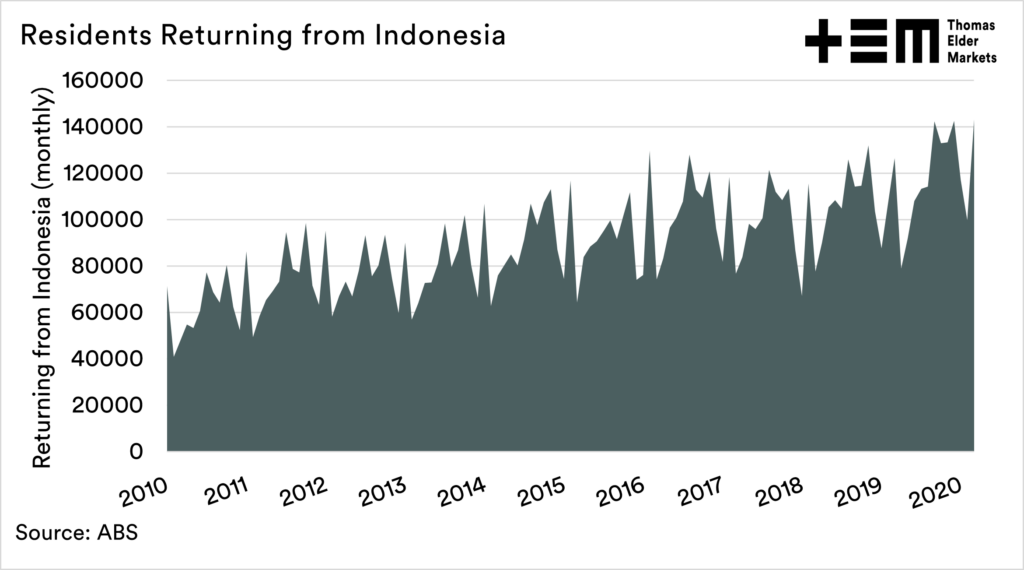

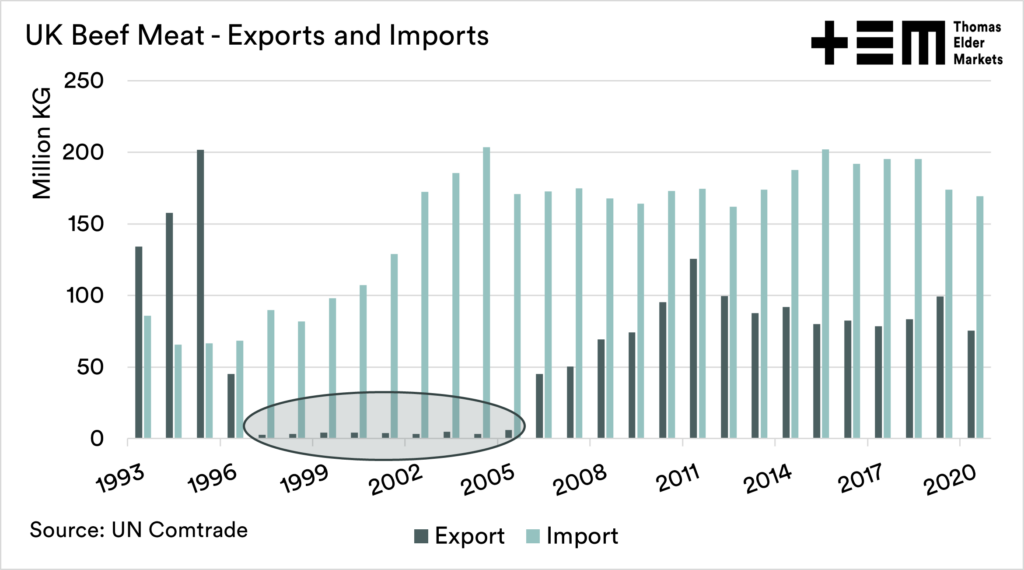

That is where the risk comes arises. I haven’t been to Indonesia, but Australians seem to love it. The chart below shows the number of arrivals back into Australia from Indonesia each month.

On average, between 2015 and 2020, 103k travellers were arriving back from Indonesia every month or about 12% of all overseas travellers.

The sheer volume of people arriving from Indonesia is a huge concern. After spending the week imbibing bintangs or whatever other concoctions, they may not have biosecurity front of mind.

Hasn’t it always been a risk?

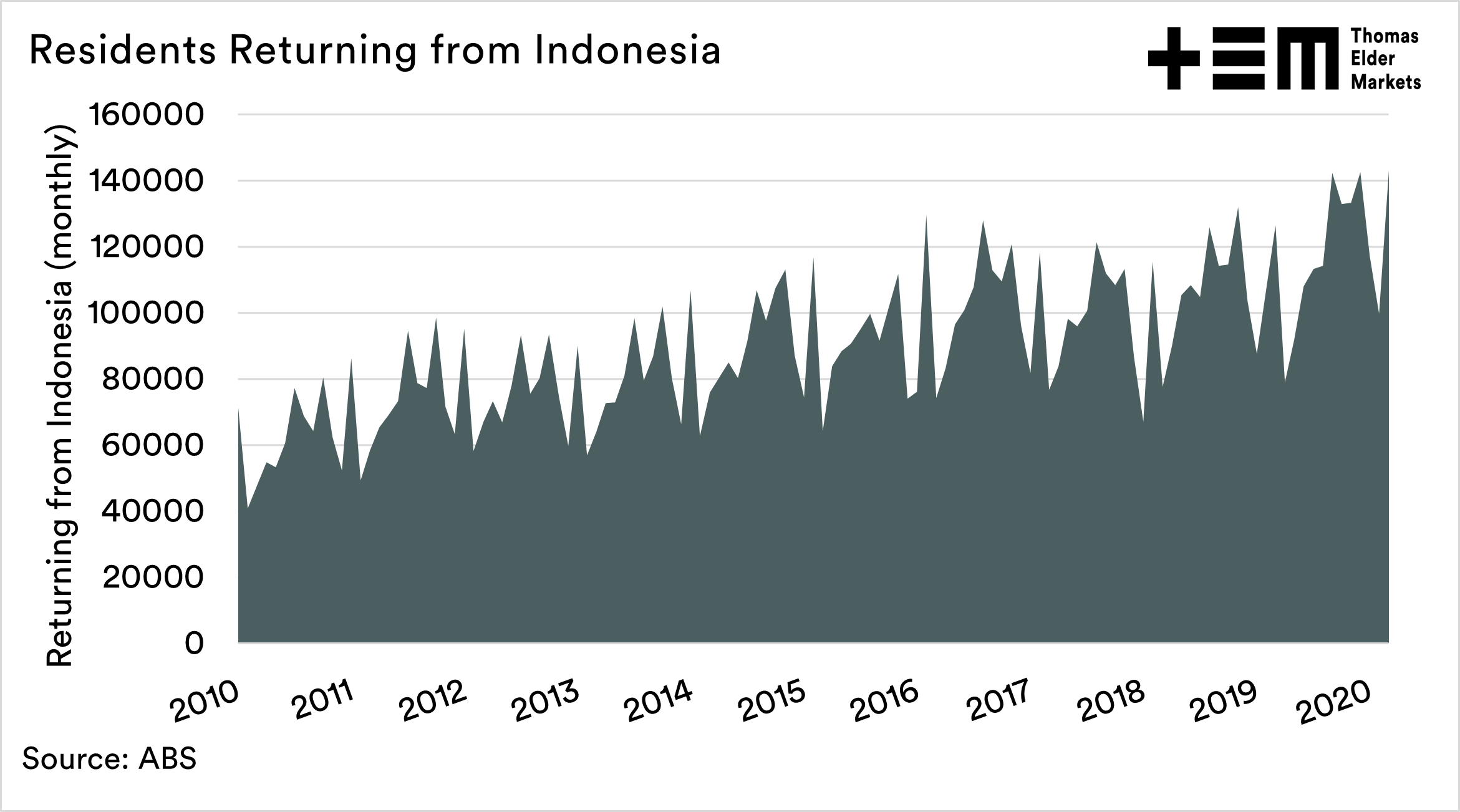

FMD has always been a significant risk; the map below shows the countries worldwide that have reported cases within the past five years. Many have travelled from these countries to Australia during this period (excluding the COVID times).

The risk of an FMD outbreak in Australia has been given a probability of 9% (1%/19%), and this will be examined this week, and in all likelihood, will be increased.

We should not have waited until FMD, or any disease was close to get the required attention. We have risks from FMD, African Swine Fever and Lumpy Skin Disease.

Luckily it has been front and centre of a number of organisations within agriculture, including but not limited to Sheep Producers Australia, Wool Producers Australia, and Australian Pork Limited.

What would the impact be?

We focus on short articles designed to give quick insights on the EP3 website. Our private work is a lot more in-depth (see here).

To find out the impact of an FMD, we recommend reading the ABARES report written in 2013 (see here) and the summary (see here). In the event of a large scale outbreak, the cost would be 50bn over ten years. I would expect the cost to be higher in 2022 than the estimates produced in 2013.

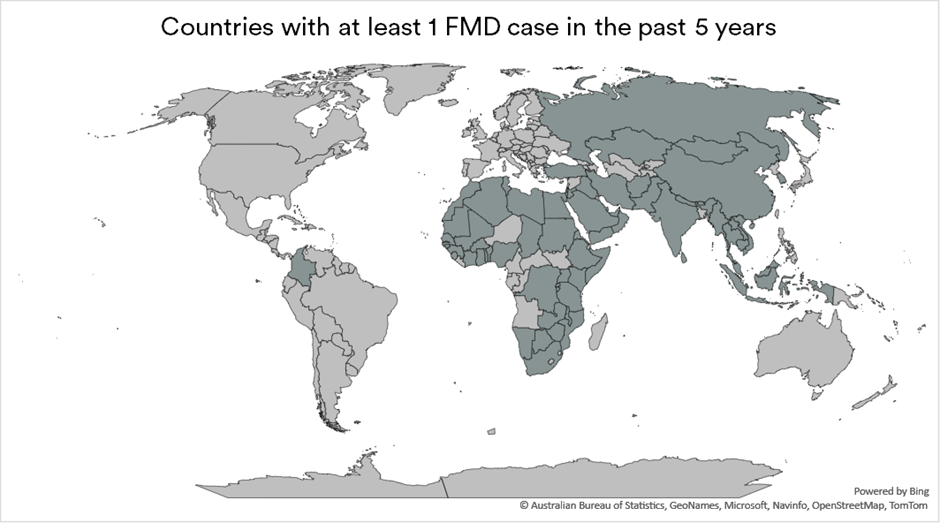

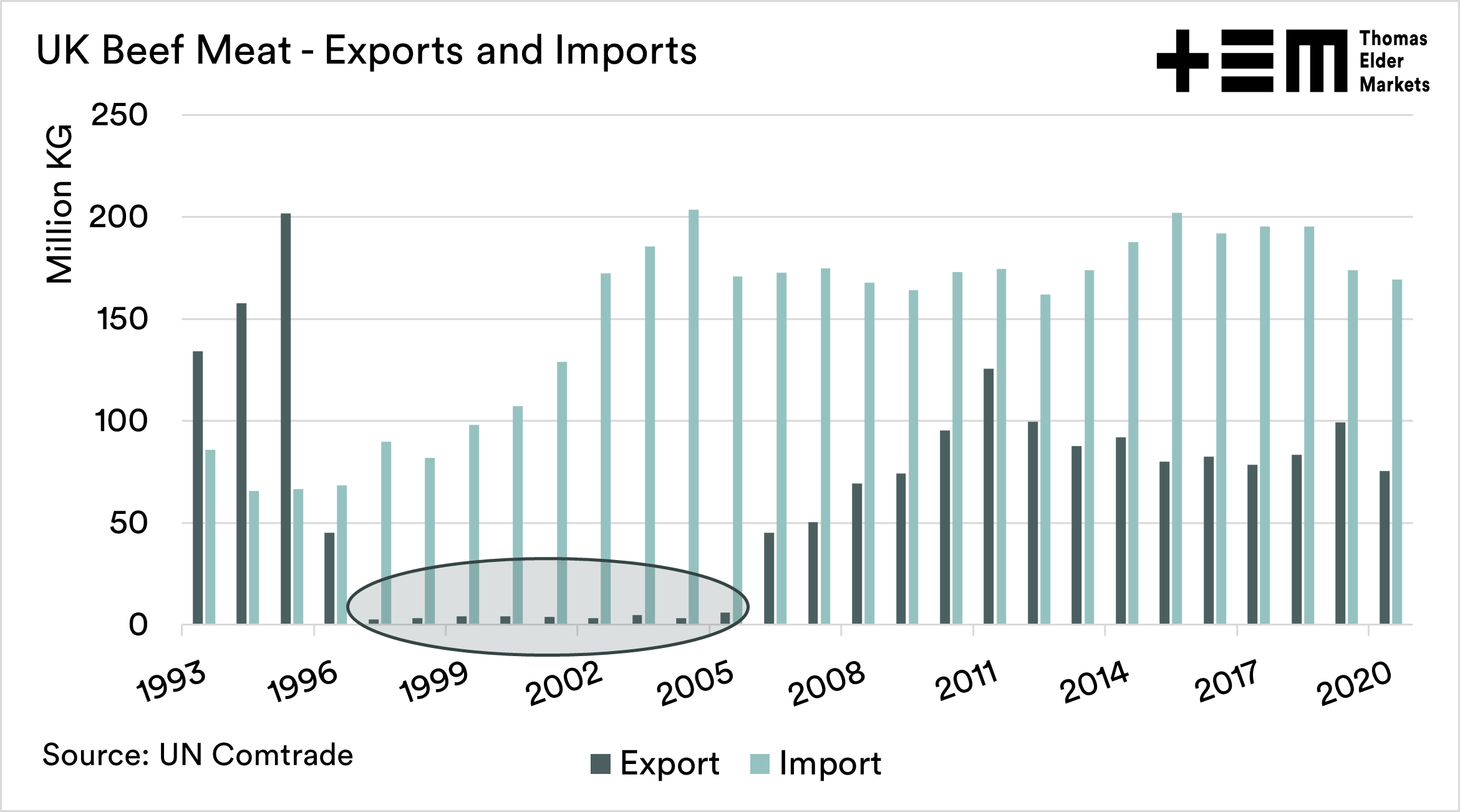

However, I wanted to highlight something that I think is important. The impact on export volumes during the 2001 FMD outbreak in the UK.

The first chart below shows the imports and exports of beef meat from 1993 to 2020. The beef industry in the UK, around the time of the 2001 FMD outbreak, was recovering from the BSE outbreak. The export of beef was effectively banned between 1996 and late 1999; the FMD outbreak caused exports to say lower for longer.

In reality, beef exports were poor from 1996 to the late 2000s due to FMD and BSE.

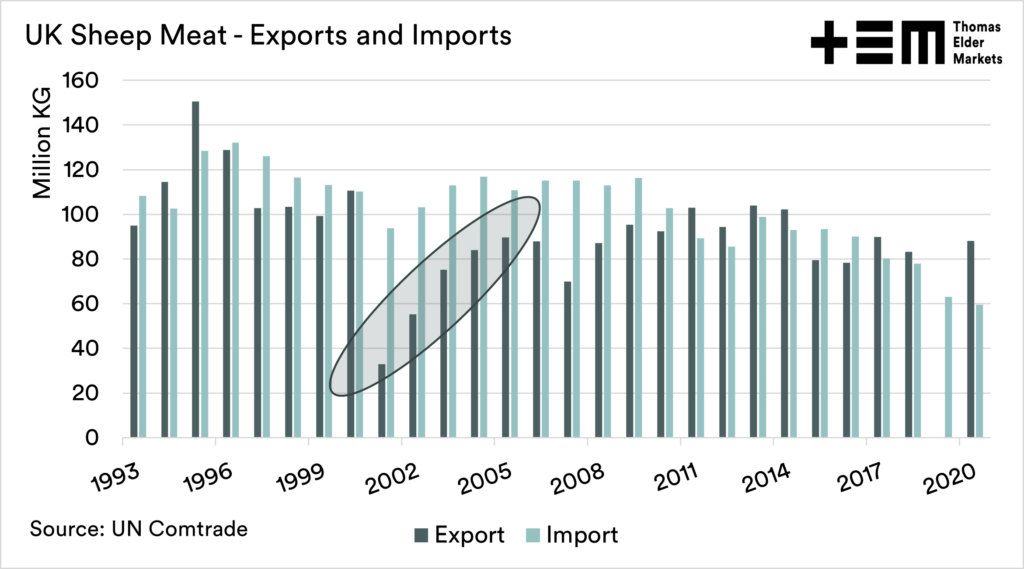

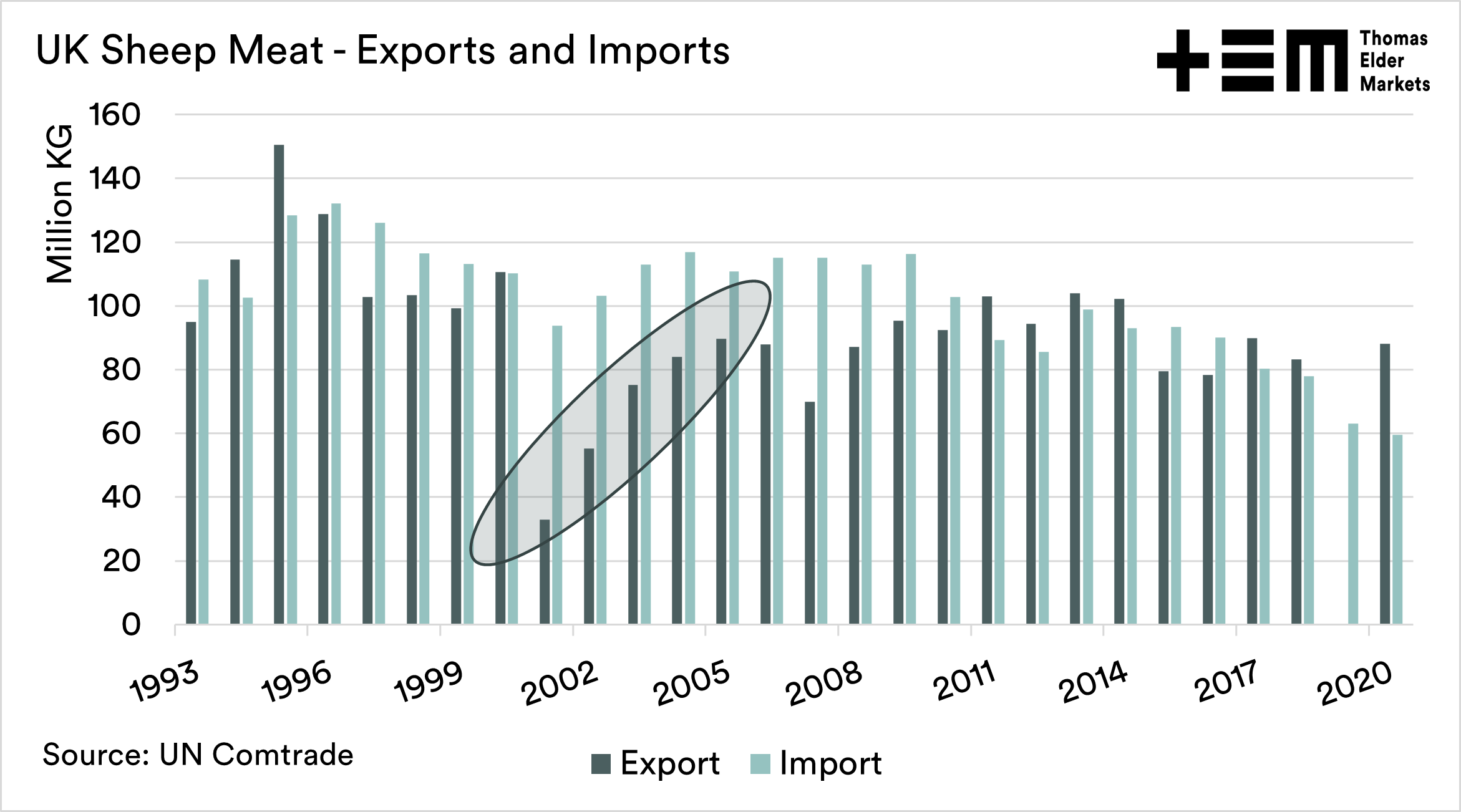

In sheep, the situation was quite distinct. Sheep weren’t affected by an existing ban. The effect was, therefore, far more immediate.

During 2001 there was a 70% drop in sheepmeat exports. It took the UK another five years to get export numbers back even close to previous export levels.

In Australia, we rely heavily on exports for our beef and sheep meat, with only 30% and 28% consumed domestically (see here).

We need to ensure that we do not damage our reputation and standing in the meat trade world.

My final thoughts on biosecurity

We must consider biosecurity and the impact that a failure can have. On-farm, it may seem like some far off policy issue for the brains of our representative bodies, but it has a significant effect.

I saw first-hand the impact that FMD had on my community. The economic impacts, through the lack of tourism and businesses shutting down. However, these pale to the psycho-social effects of the depression and suicides which followed in the wake of FMD.

I don’t want to see that here; it leaves a lingering stain on the soul of rural communities. Think of FMD as a drought that lasts a very long time.

The priorities

Firstly, keep it out. That is obvious. We have a new government, and we need the new agricultural minister to place biosecurity front and centre.

However, the mantra that I like to repeat ad infinitum comes to the fore.

Plan for the worst, hope for the best.

Therefore the second priority is containment. If the FMD or another disease gets into the community, how do we track it down and contain it, to limit the spread? Limiting the spread reduces the length of time that any export ban will be in place.

Many are against EID tags due to the cost. I can assure you that $1.30 on a tag is money well spent. It is cheap insurance, provided all the systems are in place.

If you are a livestock farmer, please ensure that you are informed about the issues related to foot and mouth disease. Read these resources; it might save your business.

- Dept of Agriculture – Full guide on FMD

- ABARES – The impact on the industry of an FMD outbreak

- Vic Dept of Agriculture – Useful descriptions

- EU Commission – Lots of resources

Support EP3

Remember to sign up to make sure you don’t miss any of our updates, these are free to access. If you want to support this service, remember to share with your network.