Rethinking the 100bn target: What the target actually should be.

When the National Farmers’ Federation (NFF) unveiled its ambitious-sounding target to grow Australian agriculture to $100 billion in farm-gate output by 2030, it captured widespread attention across the sector. It provided a clear, simple, and rallying headline for industry and policymakers alike. Yet with a few years left before 2030, it’s worth asking whether this target was ever the right one or even particularly ambitious.

This week, Julie Collins talked in parliament about the most recent ABARES forecasts for Agricultural production hitting 95bn, backed by strong collaboration from the Albanese government.

Later this month, the NFF conference will review the A$100bn by 2030 target in a panel session. The conversation will discuss how close we are to achieving this ‘ambitious’ target, with 5 years left to fill the gap. This year, the forecast is for 95bn in output, so should our advocacy bodies and government pat themselves on the back? Is the $100 billion goal even the right target?

The reality is that a significant portion of the increase in agricultural output in recent years has resulted from factors beyond the control of our advocacy bodies or the government. The weather and commodity prices have driven a significant portion of the increase in output, and as an industry, we have very little control over these factors.

The most important factor, though, is that the $100bn target doesn’t represent profits, and that is where the focus should be.

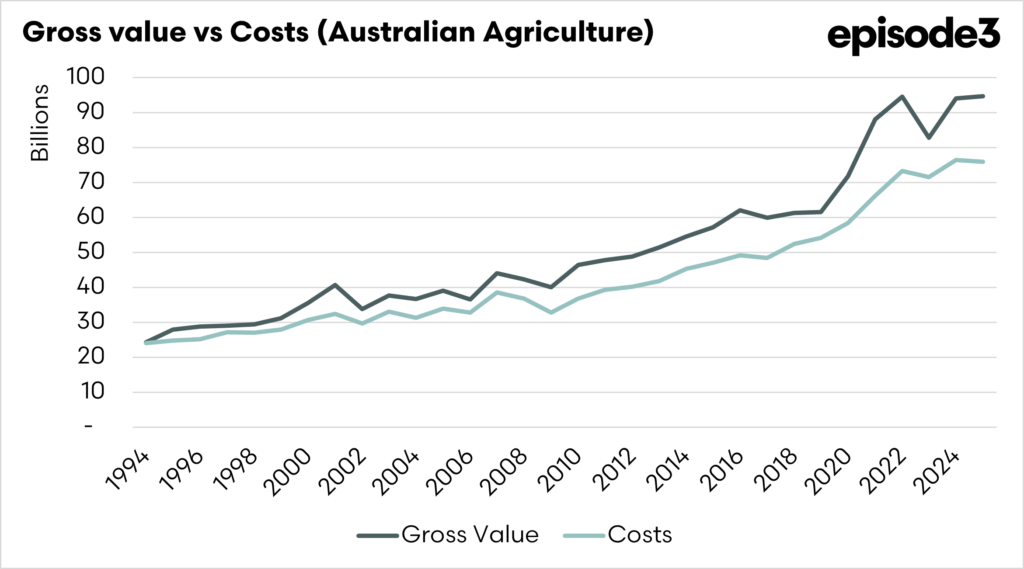

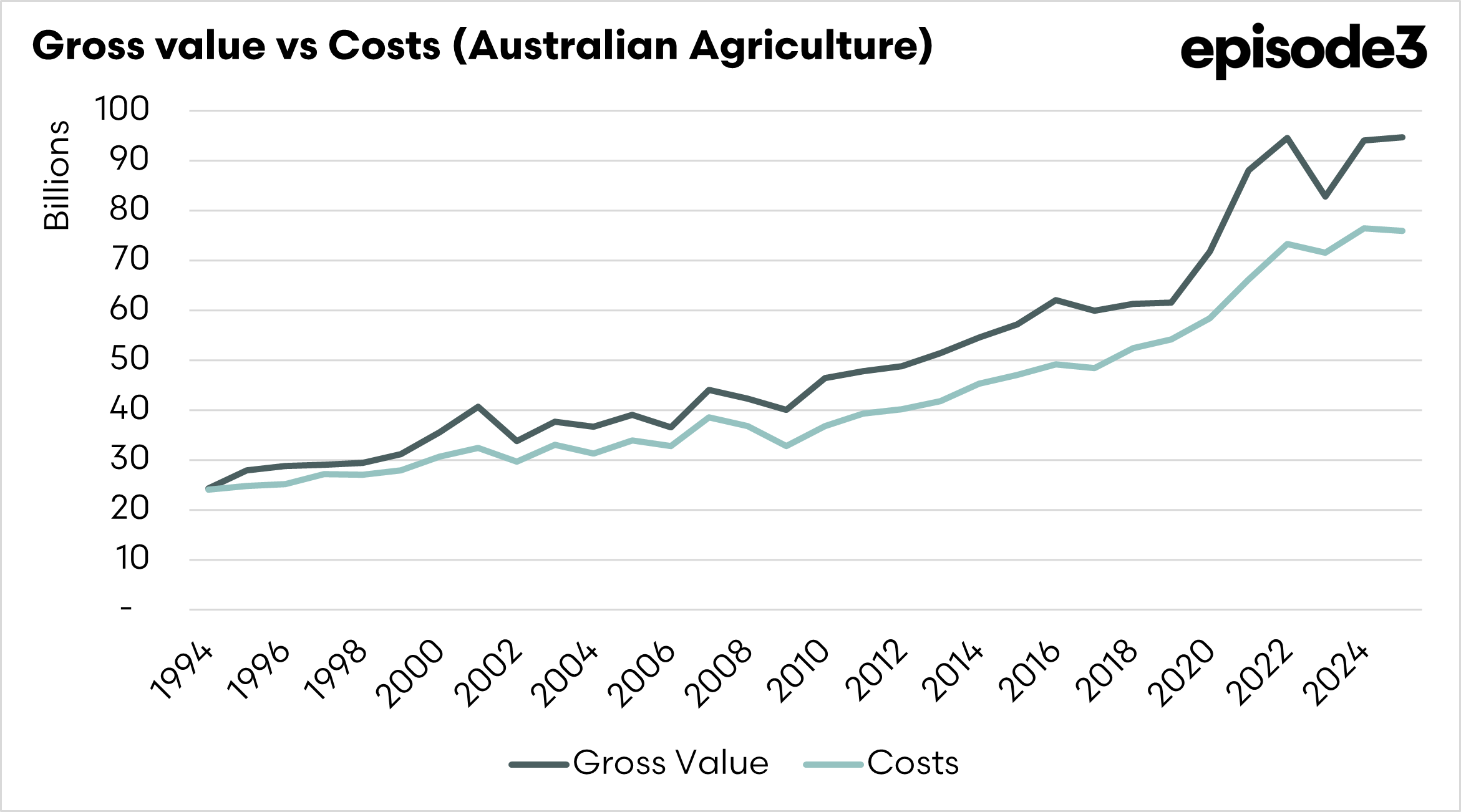

At its core, the $100 billion figure represents the gross value of production. It represents the total market value of agricultural goods produced at the farm gate, before subtracting the costs of production. As such, it reflects the size of the sector, but not the profitability, sustainability, or resilience of the businesses within it. Gross value is often helpful in assessing trade volumes, food security planning, and supply chain scale. However, when it comes to evaluating how well farmers are performing, how much income they retain, the viability of their operations, or whether they’re building wealth, gross value falls short. Would you rather sell something for $100, which costs you $10 to produce, or sell for $200 something that costs $150 to make?

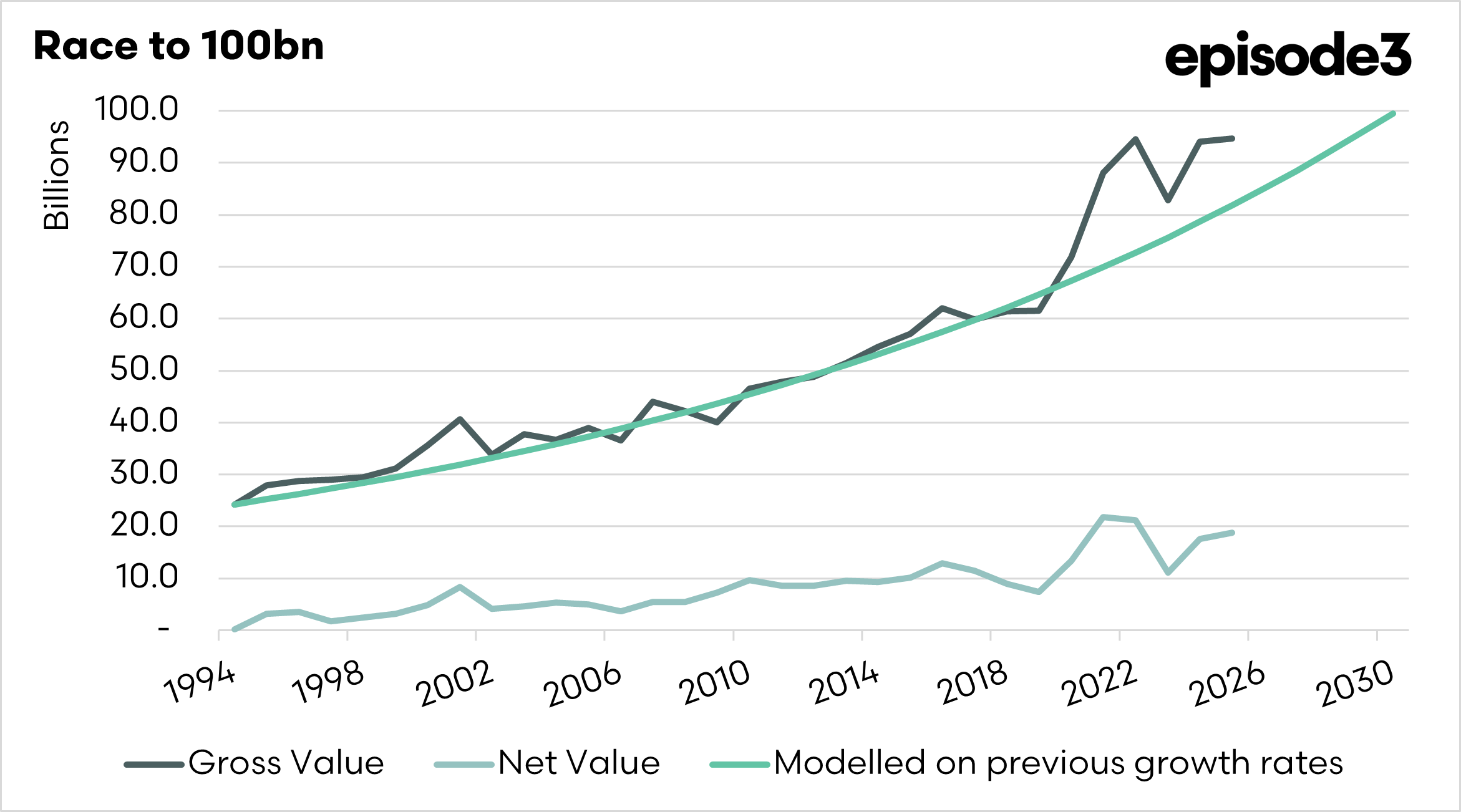

This becomes especially clear when you examine net value, the amount of income remaining after accounting for inputs such as fertiliser, fuel, labour, water, interest, freight, and maintenance. Net value gives us a clearer indication of what is actually returned to the farmer. Between 2018 and 2025, gross agricultural value increased from approximately $61.1 billion to $90.7 billion, delivering a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.79%. Meanwhile, net value over the same period increased from $8.7 billion to $15.8 billion, growing at a faster CAGR of 8.90%. So there is a good story to tell, but it’s not the gross value; it is the net value.

At first glance, the strong net value growth seems encouraging, perhaps even suggesting that farmers are capturing more of the value they generate. But it also reflects volatility, with sharp swings tied to drought years, global commodity cycles, and input cost spikes. The picture is uneven, and the gains aren’t uniformly distributed across the industry. Moreover, while net value is a better indicator than gross, it still fails to account for the distribution of income, debt levels, farm succession challenges, or resource degradation, all of which are critical to long-term prosperity.

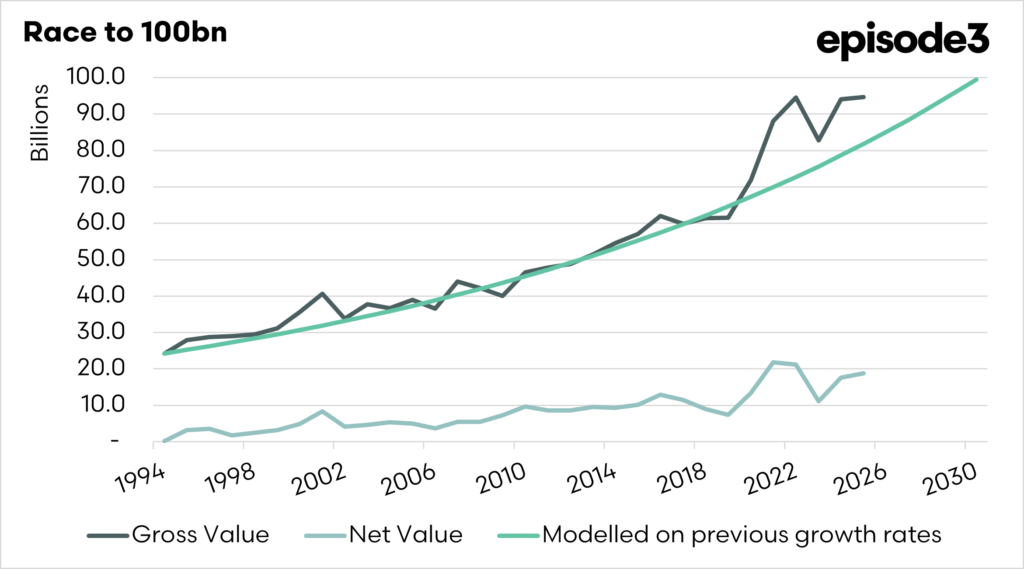

Where the conversation really needs to shift, however, is on the question of ambition. When the $100 billion target was announced in 2018, the gross value of Australian agriculture stood at about $61 billion. The headline made it sound like a significant leap forward, a near doubling of value over 12 years. However, when we examine the numbers more closely, the picture changes. If we project forward from 2018 using the long-run average growth in the sector, agriculture would naturally reach around $97 billion by 2030 even without any major structural reforms or productivity breakthroughs.

In other words, the $100 billion target was essentially a continuation of the existing trend. It wasn’t truly ambitious; it was moderately optimistic at best. The target’s appeal lay more in its round number and simplicity than in its transformational vision.

This raises serious questions about the role of consultants and strategic advisors in setting that target. KPMG, which worked with the NFF to develop the 2030 Roadmap, focused its modelling and narrative around gross output. But suppose the real goal was to ensure greater prosperity for farmers. In that case, the metric should have been net value to farm businesses or better yet, a basket of indicators capturing net income, input efficiency, risk resilience and profitability. By choosing a gross value metric, the Roadmap encouraged volume-focused thinking, rather than value-focused or resilience-based strategies.

Furthermore, pursuing a high gross output target can have perverse consequences. It may incentivise more intensive production systems, larger corporate farm models, or export dependency, potentially sidelining smaller producers and increasing exposure to global market volatility. Without matching investment in regional infrastructure, research, and on-farm risk management, the headline growth can become disconnected from actual farmer wellbeing.

In hindsight, the $100 billion target, while helpful for uniting the industry around a shared vision, was the wrong anchor for policy. It does not capture the nuance of the challenges facing Australian agriculture and sets a bar that could likely be reached without any bold intervention.

As 2030 approaches, the sector should shift its focus. The new benchmark should not be simply “how much we grow,” but how well we grow. Targets should prioritise net returns, resource efficiency, climate adaptation, and farmer wellbeing. Only then will we know whether Australian agriculture is truly thriving, not just bigger, but better.

I’d personally go for a 30bn (net value) by 2030 as the target, but it’s not quite as sexy.