Indonesia placating Trump could be negative for our wheat business

The Snapshot

- Trump-era trade dynamics remain relevant, with indirect effects on Australian agriculture through shifting trade flows and preferential US deals rather than direct tariffs.

- The 2020 Phase One deal between the US and China prioritised US agricultural exports, displacing Australian commodities like beef, barley, wine, lobster, and wood due to politically driven purchasing commitments.

- Indonesia has now agreed to double US wheat imports to 1 million tonnes annually from 2026, as part of efforts to strengthen trade relations and avoid US tariffs.

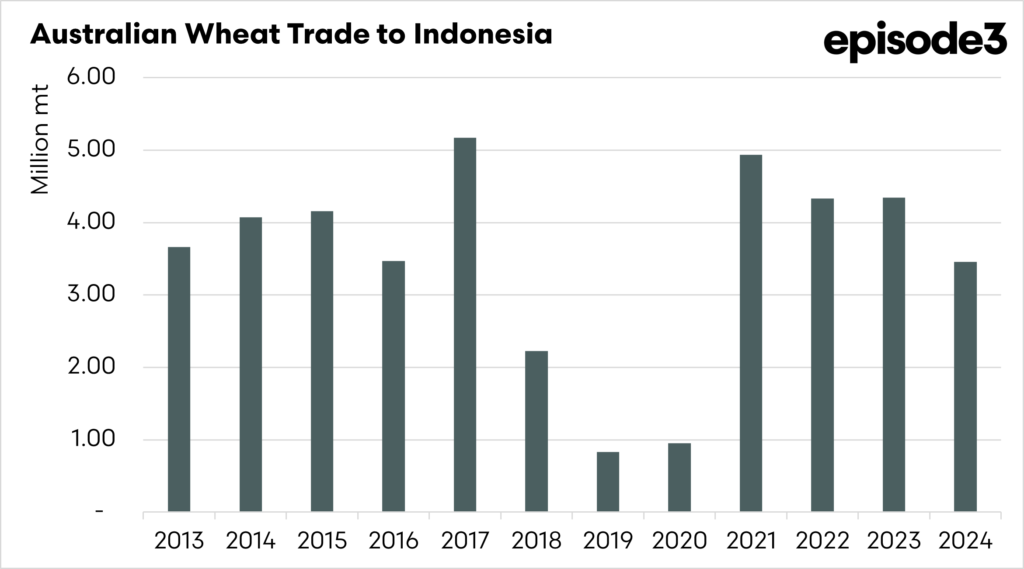

- Australia currently supplies Indonesia with an average of 4.2 million tonnes of wheat annually, meaning the new US deal could significantly erode Australia’s share of this key market.

- There’s a risk that more Asian nations may adopt similar US-favouring trade strategies, resulting in broader indirect damage to Australian agricultural export opportunities.

The Detail

Tariff talks continue to be a large part of the global landscape for grains. Australia does not have a significant direct impact of the tariffs introduced by Donald Trump, but we have the potential to be indirectly impacted, through trade agreements, which could incentivise purchases of US commodities.

We can look back at the past Trump administration and the phase one deal to learn about how this can impact our commodities.

The Phase One trade deal, signed in January 2020, aimed to ease tensions following two years of escalating tariffs between the US and China. The trade war began in 2018 when the Trump administration accused China of engaging in unfair practices, including forced technology transfers and intellectual property theft. In response, the US imposed tariffs on Chinese goods, and China retaliated with its own tariffs, including on major US agricultural exports such as soybeans, corn, and pork. This severely affected American farmers, especially in key electoral states, putting pressure on the White House to find a resolution.

One of its most prominent features was China’s pledge to increase purchases of US goods, particularly agricultural products, massively. Over two years, China committed to purchasing at least US$80 billion worth of US farm goods, effectively giving them preferential treatment over other suppliers. This redirection of trade was driven more by politics than economics, and it displaced competing nations, such as Australia.

In 2020, EP3 analysts identified nine key commodities at risk, five of which ultimately received negative attention from the Chinese government: beef, barley, wine, lobster, and wood.

This indirect trade flow issue may be seen in our trade with Indonesia. Indonesia has reached a new agreement, which will see them double their wheat purchases from the United States.

Indonesia has signed an agreement to double its imports of US wheat to 1 million tonnes annually from 2026 to 2030, valued at US$ 1.25 billion. The deal, led by the Indonesian Flour Mills Association and US Wheat Associates, is part of broader efforts to strengthen trade ties with the US and potentially avoid new tariffs on Indonesian exports.

As one of the world’s largest wheat importers, Indonesia relies entirely on foreign supply, with demand driven by population growth and a robust milling sector. The US currently holds around 9% of Indonesia’s wheat market, and this move is expected to support both domestic food security and US export interests.

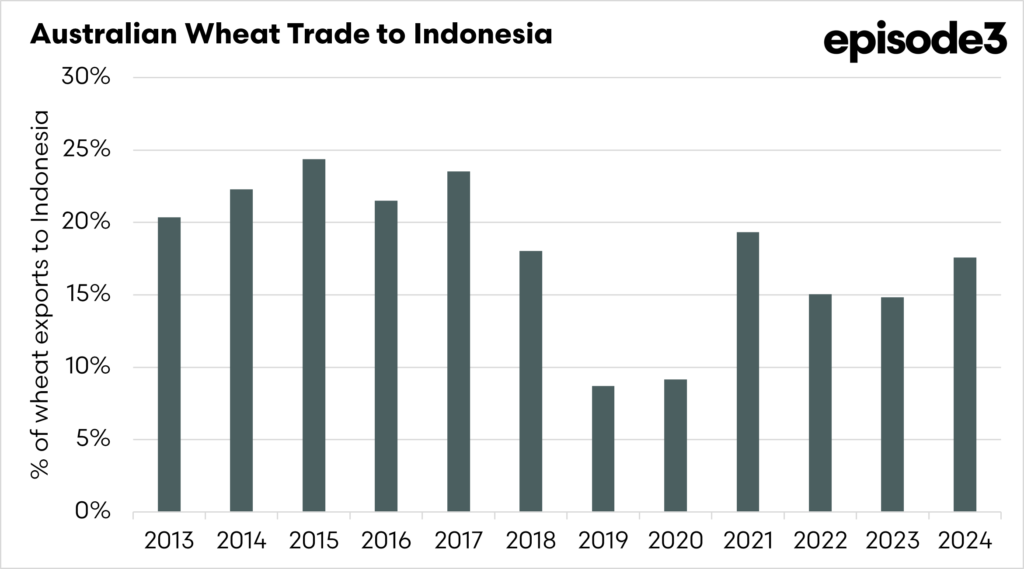

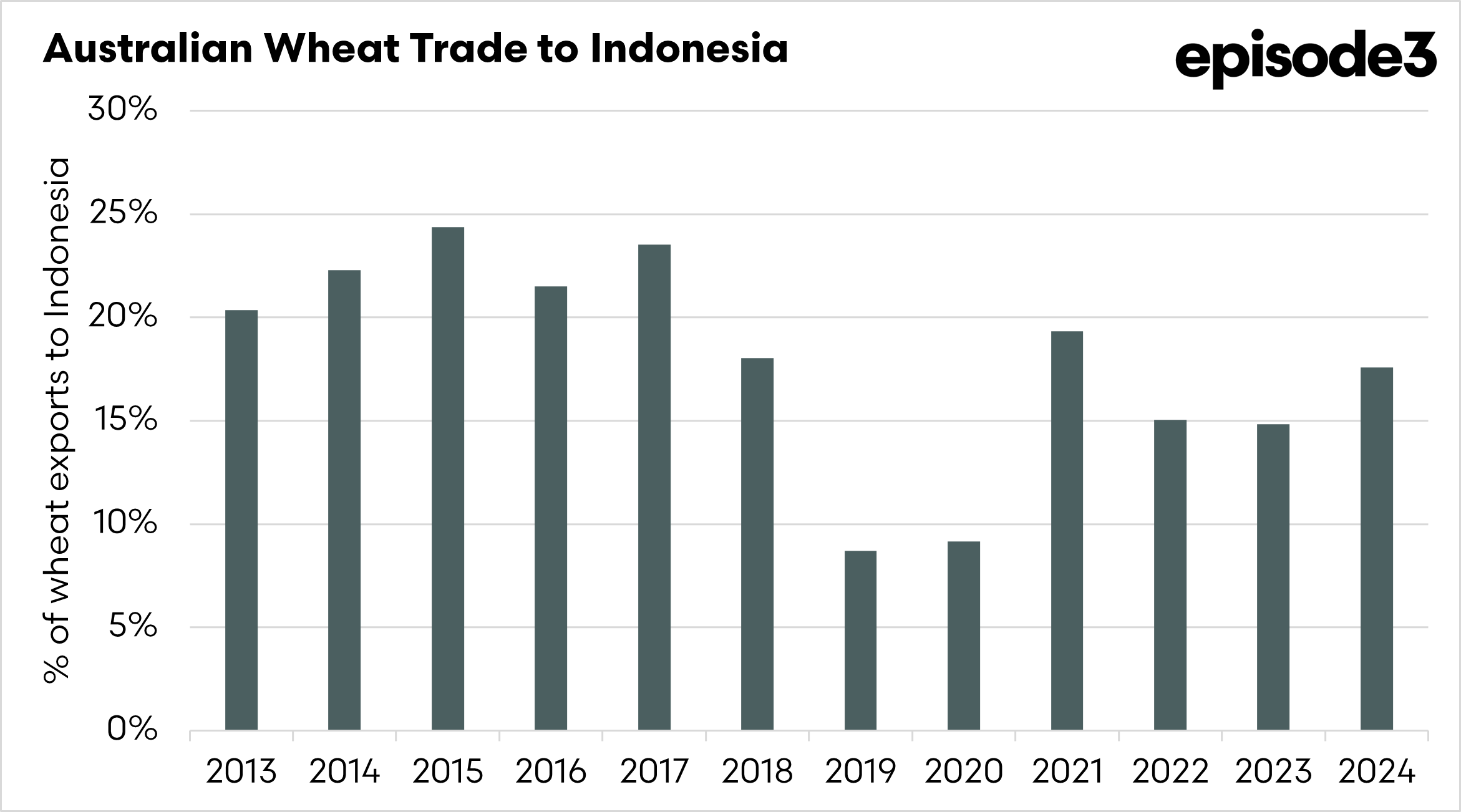

Indonesia purchases a significant quantity of wheat from Australia, including, on average, 4.2 million tonnes per year over the past four years, and has purchased at least 15% of our wheat exports on average, excluding our major drought years.

The move to placate the Trump administration will mean that Indonesia will have 1 million tons, which they will have to purchase from the USA, reducing our access to this market.

The concern is that other Asian nations may follow suit, and we end up with a series of trade agreements that prefer US agricultural commodities.

The key point is that while the trade tariffs will not have a major direct impact on Australian agriculture, their indirect impact can be felt just as heavily.