A battle ahead for barley

The Snapshot

- In May 2020, China applied tariffs to Australian barley of 80.5%.

- It is unlikely that these tariffs were introduced in response to requests for investigations into CV-19 by the Australian government.

- In early 2020, China agreed to the phase 1 deal with the USA. This effectively requires China to purchase American agricultural products. This likely would have lead to substitution of barley with other products where possible.

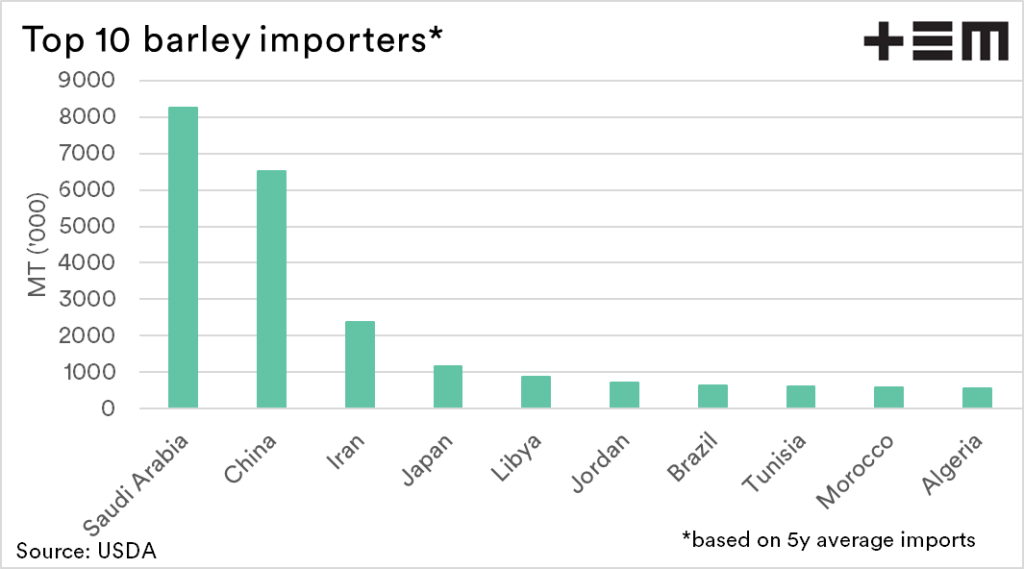

- Filling the whole left by China will be difficult. They are currently the 2nd largest importer of barley behind Saudi Arabia.

- In recent years Saudi Arabia has purchased from alternate origins, and there are now other short term competitors.

The Detail

The last few years have seen unprecedented changes to the fabric of geopolitics. We have Brexit, the war of words between the United States and China and in recent times, COVID-19. One of the first casualties of the machinations of global superpowers was Australian barley. In May 2020, China applied a tariff to Australian barley of 80.5%.

What really happened to barley, were we punished? And where will our barley go?

The story of the battle for barley starts before the recent droughts. In 2016 the weather gods were amenable, resulting in a record barley crop of 13.5mmt. To put this in perspective during the previous ten years the country had averaged 7.7mmt.

As anyone with even a rudimentary grasp of economics will understand, if you have an abundant supply of a commodity, and demand which is relatively stable, then you end up with lower prices.

As the country exported our humongous surplus, large volumes of barley were shipped to China at prices that were at decade lows. In this case, usually, the customer is happy as they receive cheap produce. Generally, the farmer isn’t that happy with the price but has the volume to somewhat make up for the discount, so overall their revenue situation is still pretty healthy.

However, in late 2018 the Chinese government launched an investigation into allegations of anti-competitive dumping. This shocked most producers, as all of them, would have been more than willing to sell their barley at higher prices to China.

This investigation was due to be completed in late 2019; however, an extension was granted unitl May 2020. As expected, China enforced a hefty tariff of 73.6% as an anti-dumping duty and 6.9% as a countervailing duty.

Many commentators from outside of agriculture assumed that the introduction of a tariff was in retaliation for Australian comments regarding investigations into CV-19.

However, a likely more significant cause was the trade deal between the US and China. In early 2020 China signed the ‘phase 1’ trade deal with the USA to purchase a target of US$40bn in agricultural produce during 2020, to bring a stalemate to the festering trade scuffle between the two giants. This target was an astronomical task considering that in 2017, US exports to China only reached US$23.8bn. If China was to achieve the objectives set, then US produce would have to be prioritised.

It is far more likely that China enacted duties to ensure that American agricultural products such as corn and soybeans were imported.

The combined duties of 80.5% have made Australian barley uncompetitive into China. As Australia recovers from drought and all going well, a sizeable exportable surplus is likely to be available. What are we going to do with it all?

During the past decade, the world has exported around 24mmt of barley, 21% of which has originated in Australia. China has been a home for 6.5mmt during the past five years, a substantial destination which is now effectively closed unless heavily discounted.

The world’s top ten importers constitute close to 90% of the overall customer base for barley. The largest buyer is Saudi Arabia at 8.2mmt. As a dry nation, this barley is used to feed sheep rather than produce beer or sprits.

Historically, Saudi Arabia had been the largest customer for Australian barley. However, was usurped by China more recently. Saudi Arabia has not been waiting patiently for Australia to return as a significant supplier. To meet their demand, they have been purchasing from former Soviet bloc nations, along with Europe.

When we remove Saudi Arabia and China, the rest of the importing nations for Australian barley drop in importance quite rapidly. Our barley will need to be competitive to get a foothold back into Saudi Arabia, a task made more difficult by our appreciating Australian dollar.

Furthermore, to make matters worse, there are potentially two new entrants to the barley export market. The first being the United Kingdom with an exportable surplus of >1mmt., The UK face potential tariffs of €93/mt for exports to the EU in 2021 as Brexit is finalised. They will then be forced to sell to countries outside of Europe. The obvious choice for their shipments is the north African nations and the middle east.

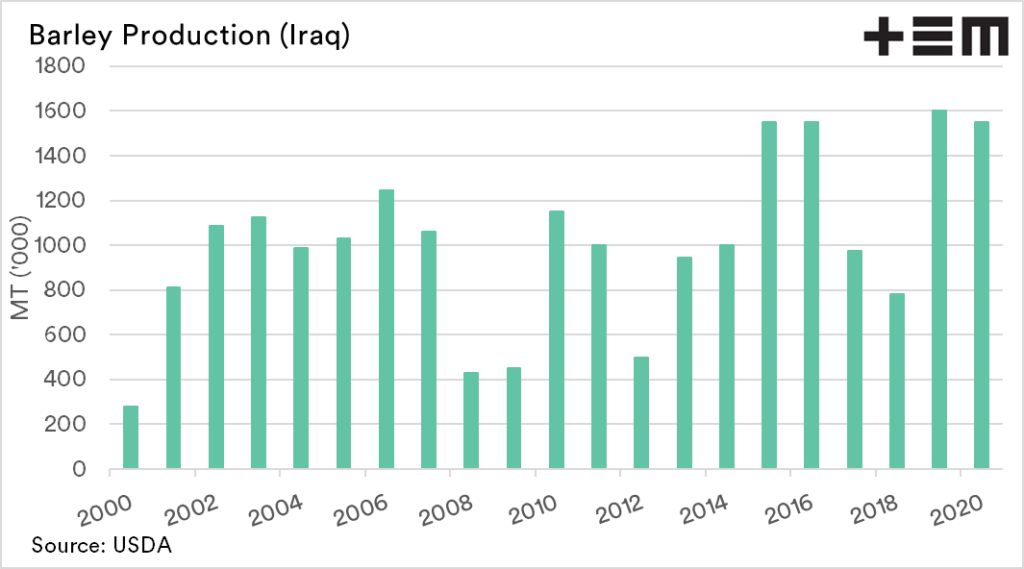

The next new entrant, and perhaps more surprisingly, is Iraq. In recent years they have built up enough stockpiles of barley to commence exports, with the government announcing >800kmt of barley to be marketed in the coming year.

Australia will be able to find a home for its barley. However, it will have to price it competitively to win sales in a well-supported market with new competitors emerging.