Afghanistan: A looming food crisis?

The Snapshot

- Afghanistan has been in almost constant conflict since 1979.

- In the past twenty years, the population has boomed from 20.7m to 37.2m.

- The same period has also seen undernourishment fall, from 50% to 26% of the population.

- Production, imports and yields of wheat have all increased dramatically.

- Kazakhstan is the largest supplier, mainly of flour.

- There are risks that traders will not trade with the new Afghan risk due to counterparty risk.

- The larger population in Afghanistan will make it harder for the new Taliban government to feed if they are shut off from the world.

- Lack of access to food has been shown to cause destabilisation around the world.

- Large volumes of wheat/flour may be rediverted to other buyers, potentially our customers.

The Detail

Afghanistan is a nation with a turbulent history, not just in the past twenty years but since the middle of the 1800s. Afghanistan has been in a state of almost constant war since 1979, with Russia, the allies, and civil wars.

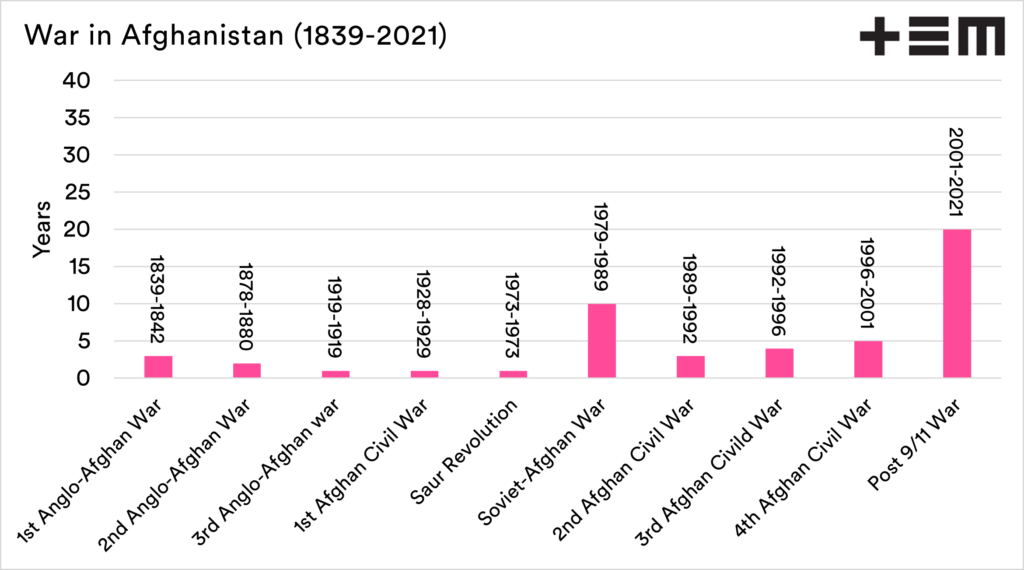

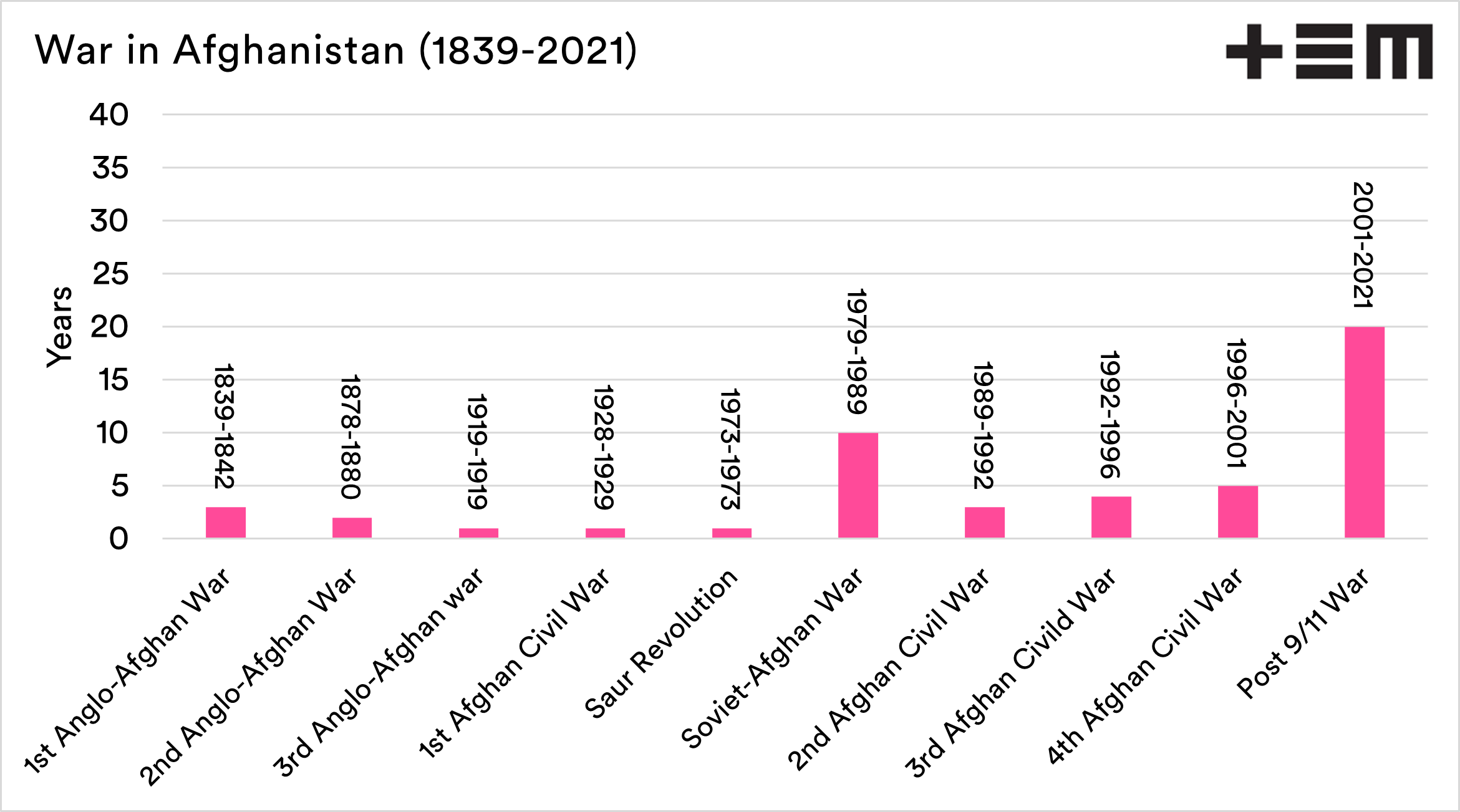

The chart below shows the length and periods of war since 1839. The numerous conflicts in Afghanistan have stifled development. There were improvements during the past twenty years but is seems likely that things may regress in the immediate future.

This raises the question about food supplies. I thought it was worthwhile to look into the data and see what the situation is in relation to wheat.

Development in Afghanistan

Whilst Afghanistan is still heavily underdeveloped compared to large parts of the world, the situation there has improved in the past twenty years. The population has increased from 20.7m in 2000 to 37.2m in 2018. A huge rise.

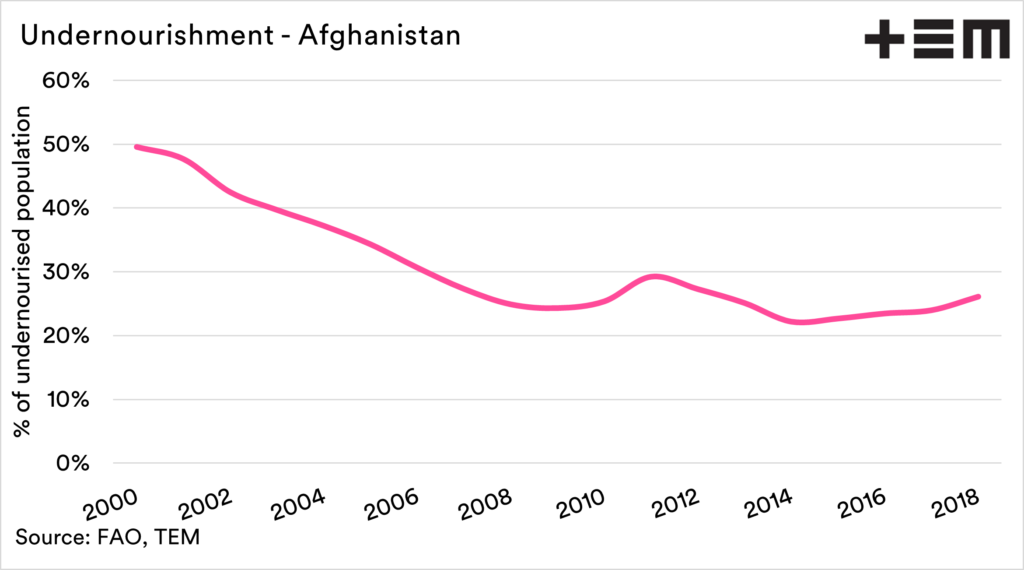

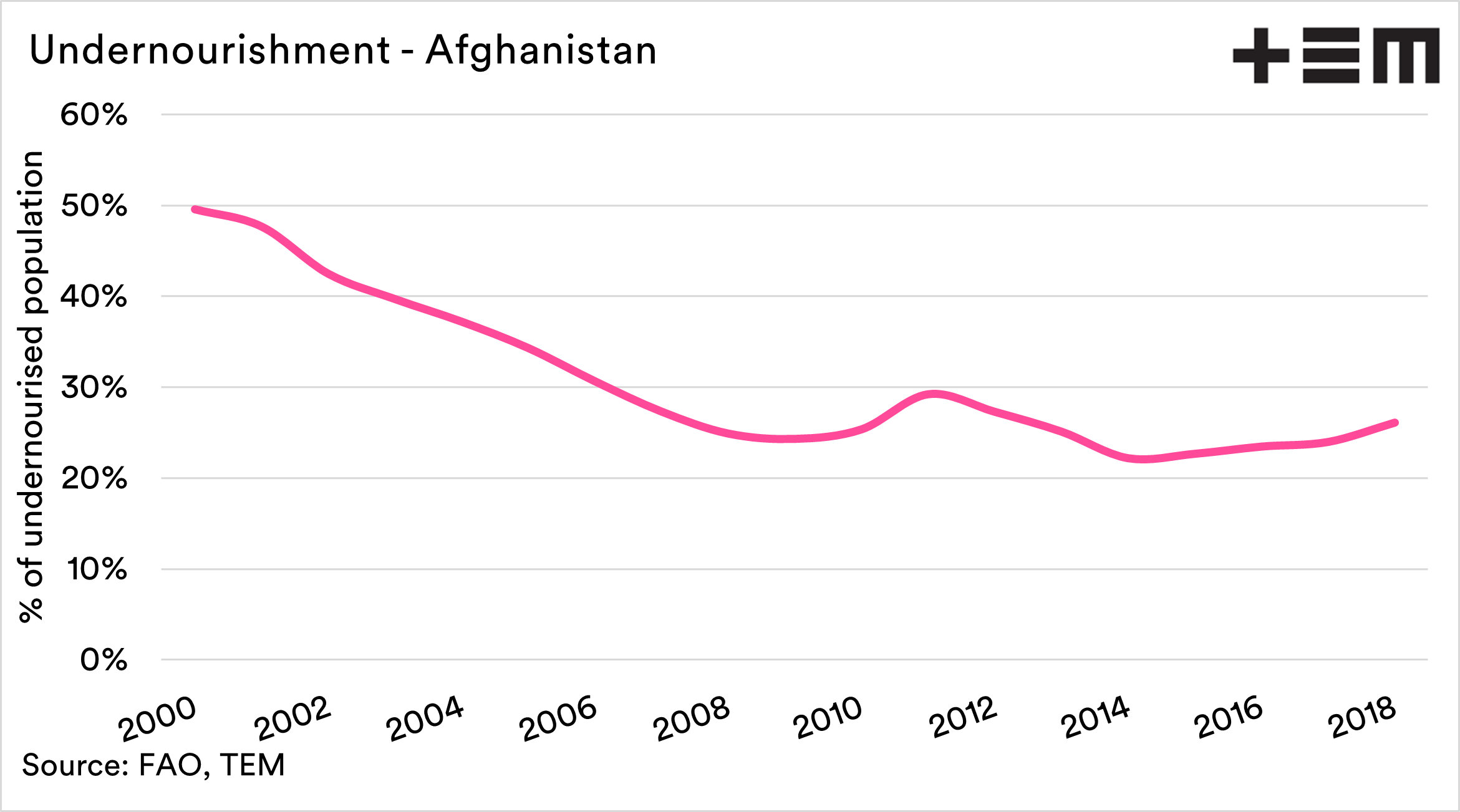

In the same time, undernourishment has fallen. At the turn of the century, Afghanistan had 50% of the populace suffering from undernourishment. Recent data shows undernourishment at 26% of the population.

The improvement in nourishment is impressive, as it comes at a time of massively increased population. The reality is that a large part of the population are still malnourished, and the return of the Taliban could see a degrade in these improvements.

Supply and demand

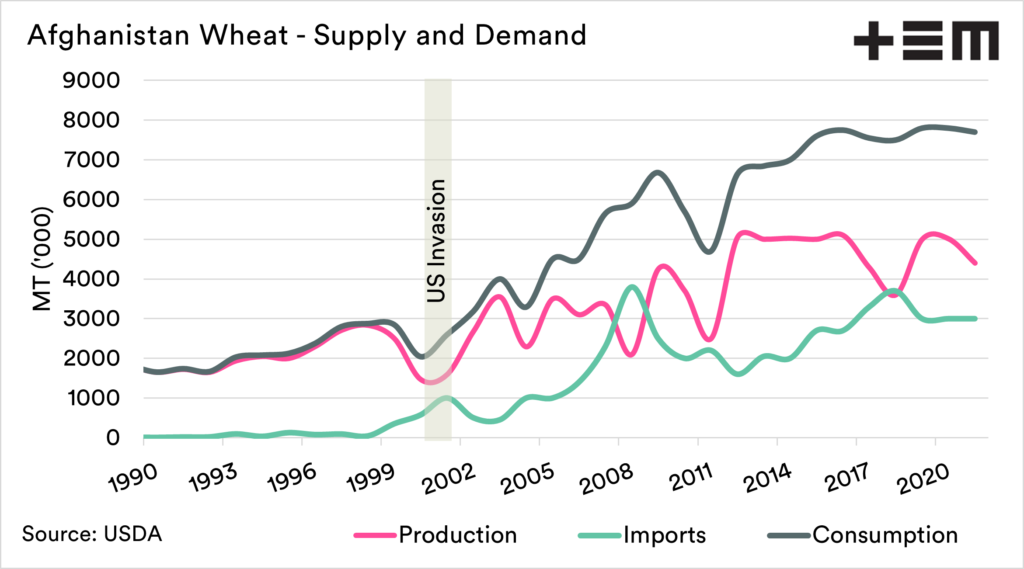

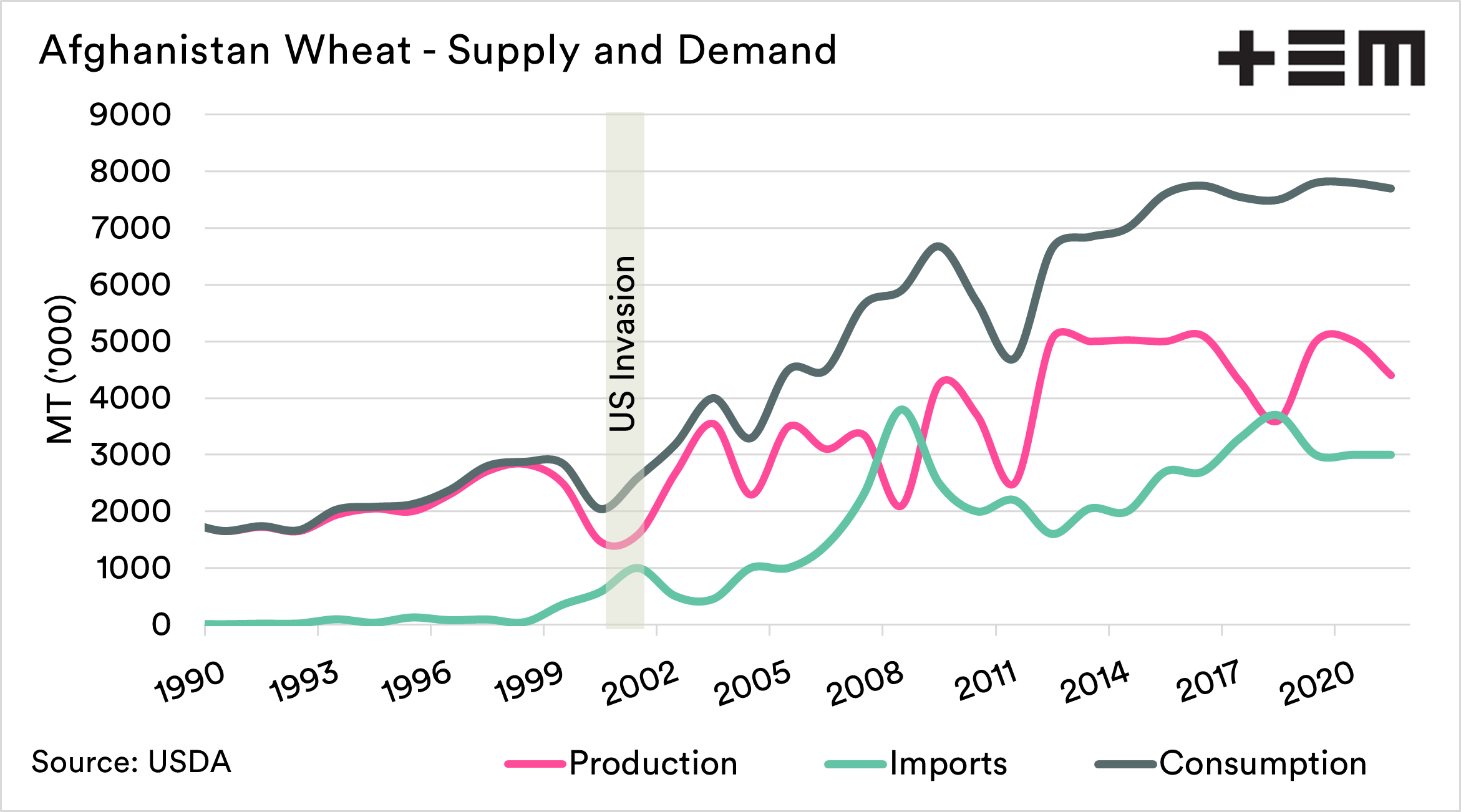

The chart below shows the production, imports and consumption of wheat in Afghanistan since 1990.

The wheat supply and demand in Afghanistan has changed dramatically since the invasion in 2001. There have been huge increases across all factors.

The following is the change between the average of the first five years of allied occupation and the last five.

- Production – 2.3mmt to 4.4mmt

- Imports – 700kmt to 3.2mmt

- Consumption – 3mmt to 7.6mmt

- Yield – 1.2mt/ha to 2.03mt/ha

The introduction of aid, and development of agriculture through various training programs has assisted in developing the industry. But what next?

Afghanistan is reliant on imports of wheat to feed the populace. In the past decade, imports have been 48 to 76% of local consumptive demand.

When the Taliban were last in power, the population and consumption of wheat were substantially lower. If they want to ensure their people are fed, the Taliban need to be a part of the global community.

This will involve buying from the international market. Where do they buy from just now, and how will they be welcomed?

A focus on one supplier

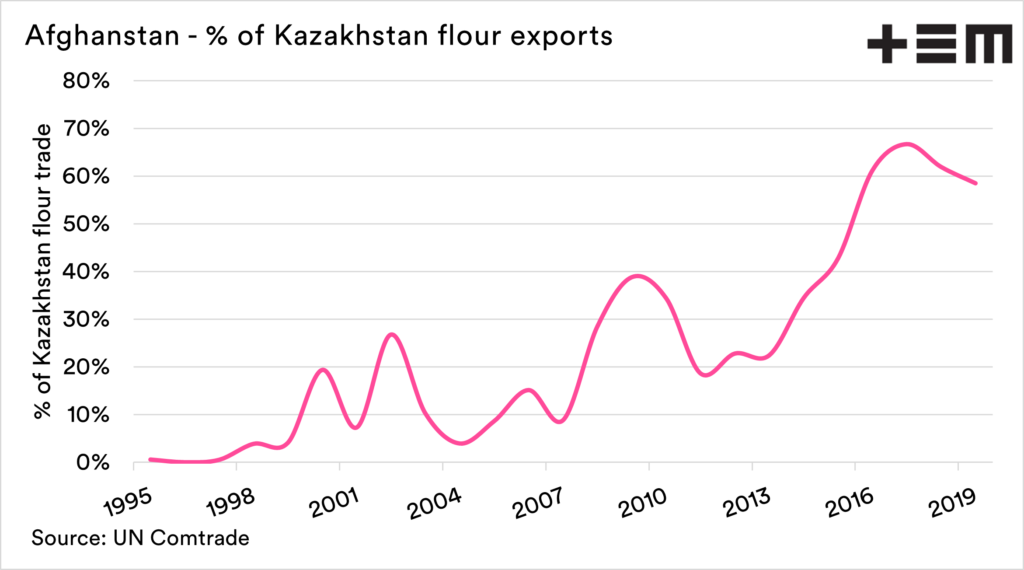

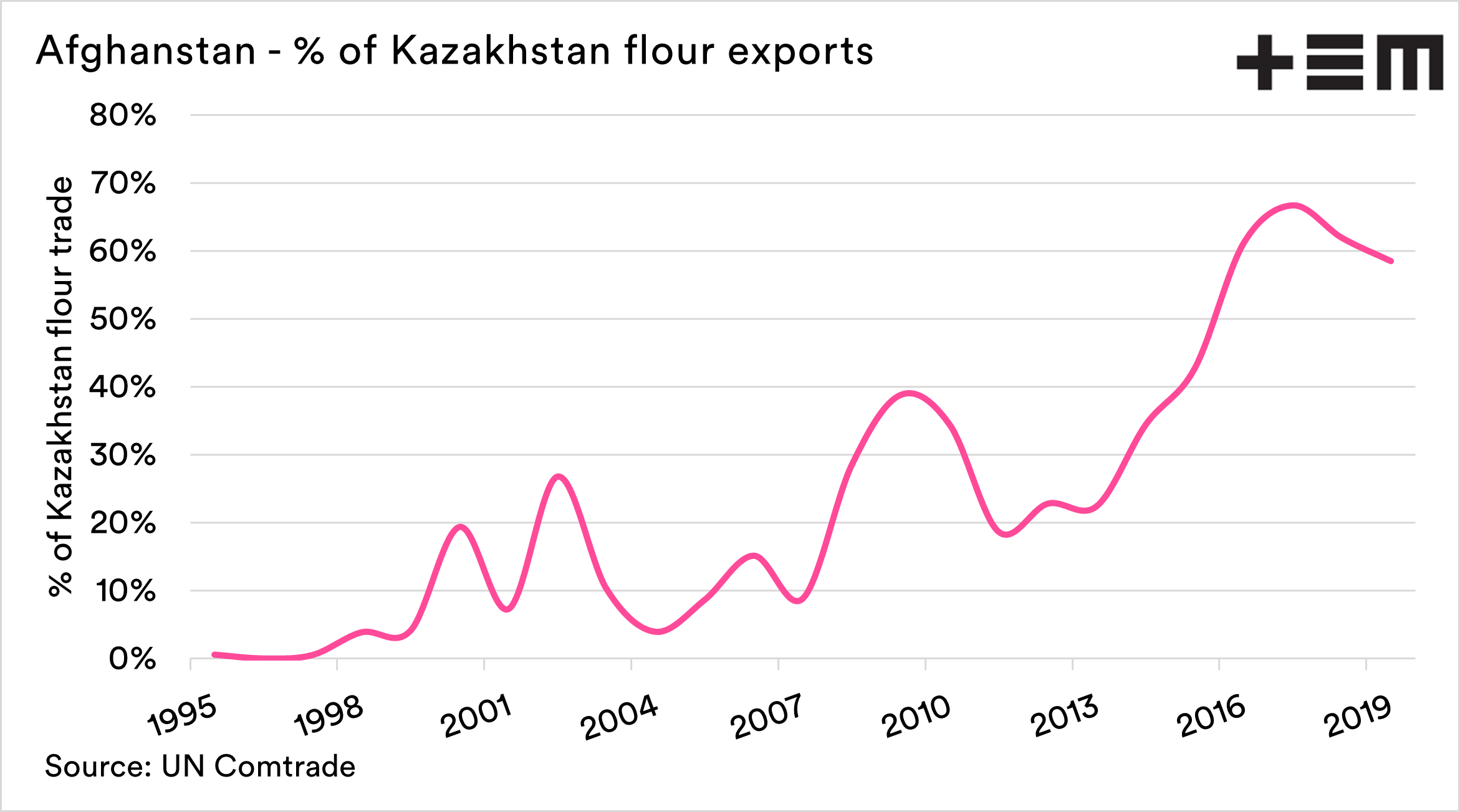

The biggest supplier to Afghanistan is Kazakhstan, one of the worlds largest wheat exporters. Much of the trade with Afghanistan is in the form of flour as opposed to straight wheat.

In recent years Afghanistan has been a customer of nearly 70% of Kazakh flour. Will they continue to be so reliant?

If they stop supplying to Afghanistan, then this will be a poor outcome for the Afghan people. This will also place further wheat onto the global market, potentially flowing to some of our key markets.

When a farmer sells grain to a trader, there is always an element of counterparty risk (see here); the same occurs when a trader sells to another trader.

Are traders willing to take on the counterparty risk of exporting to a nation that appears to be perched on the precipice? A trade into Afghanistan has a lot of questions.

- Will there be sanctions trading to Afghanistan?

- Will you get paid if you sell there?

- What recourse will there be if anything goes wrong?

Afghanistan has largely been propped up by foreign aid for the past twenty years, and this is now likely to stop. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has suspended access to loans to the new Afghan government in recent weeks.

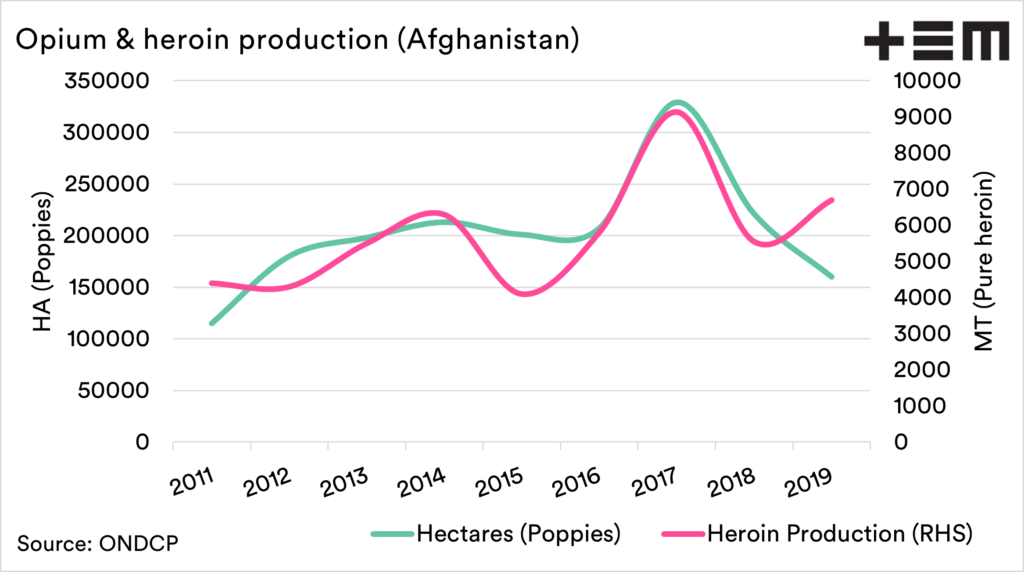

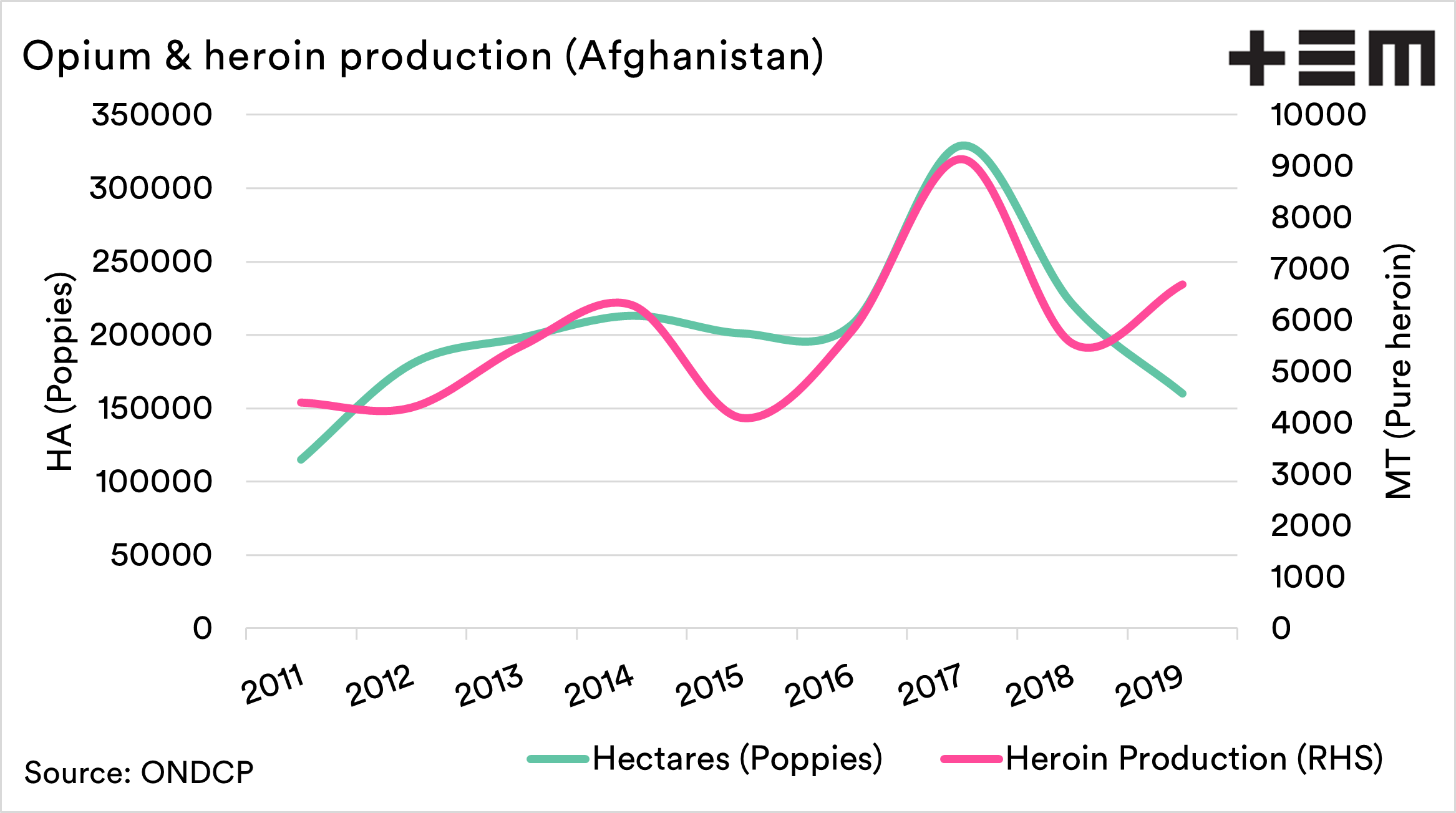

Suppose Afghanistan returns to being a pariah state. In that case, they will find it difficult to get access to funds, aside from the taxation of opium production (see above).

To feed a population that has ballooned in the last twenty years will require funds, to purchase food but also the tools to grow crops. A starving population could result in further destabilisation. That is the last thing we want to see.

The Taliban have inherited a very different country from the one that they left control of in 2001, and it has enormous challenges. These challenges can’t be solved by isolating.

All in all, it’s a horrible situation that could get worse. We feel for all the innocent people there.

If you liked reading this article and you haven’t already done so, make sure to sign up to the free Episode3 email update here. You will get notified when there are new analysis pieces available and you won’t be bothered for any other reason, we promise. If you like our offering please remember to share it with your network too – the more the merrier.