Australia isn’t short of fuel, it is short of a plan for farmers

Summary & key takeouts

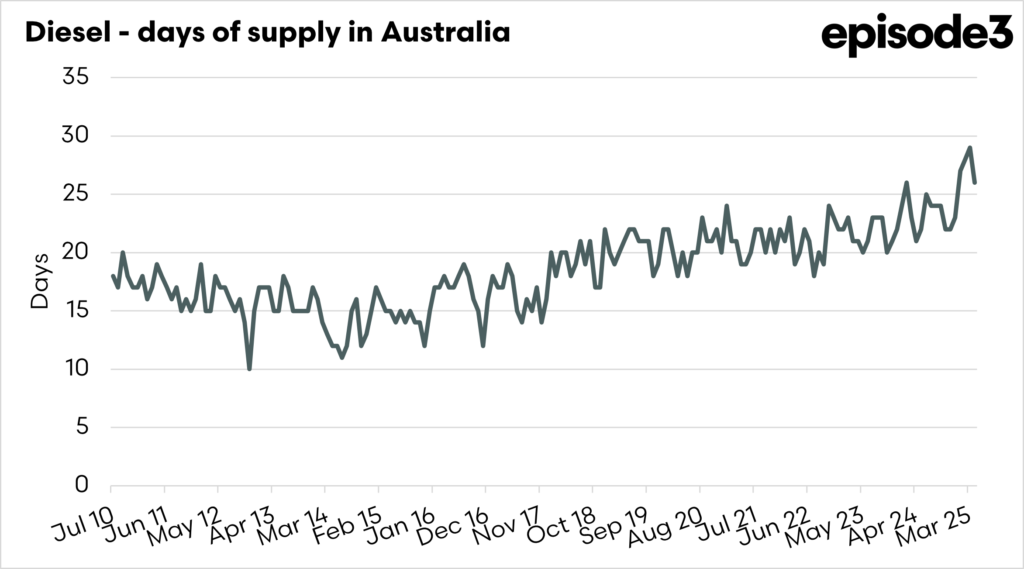

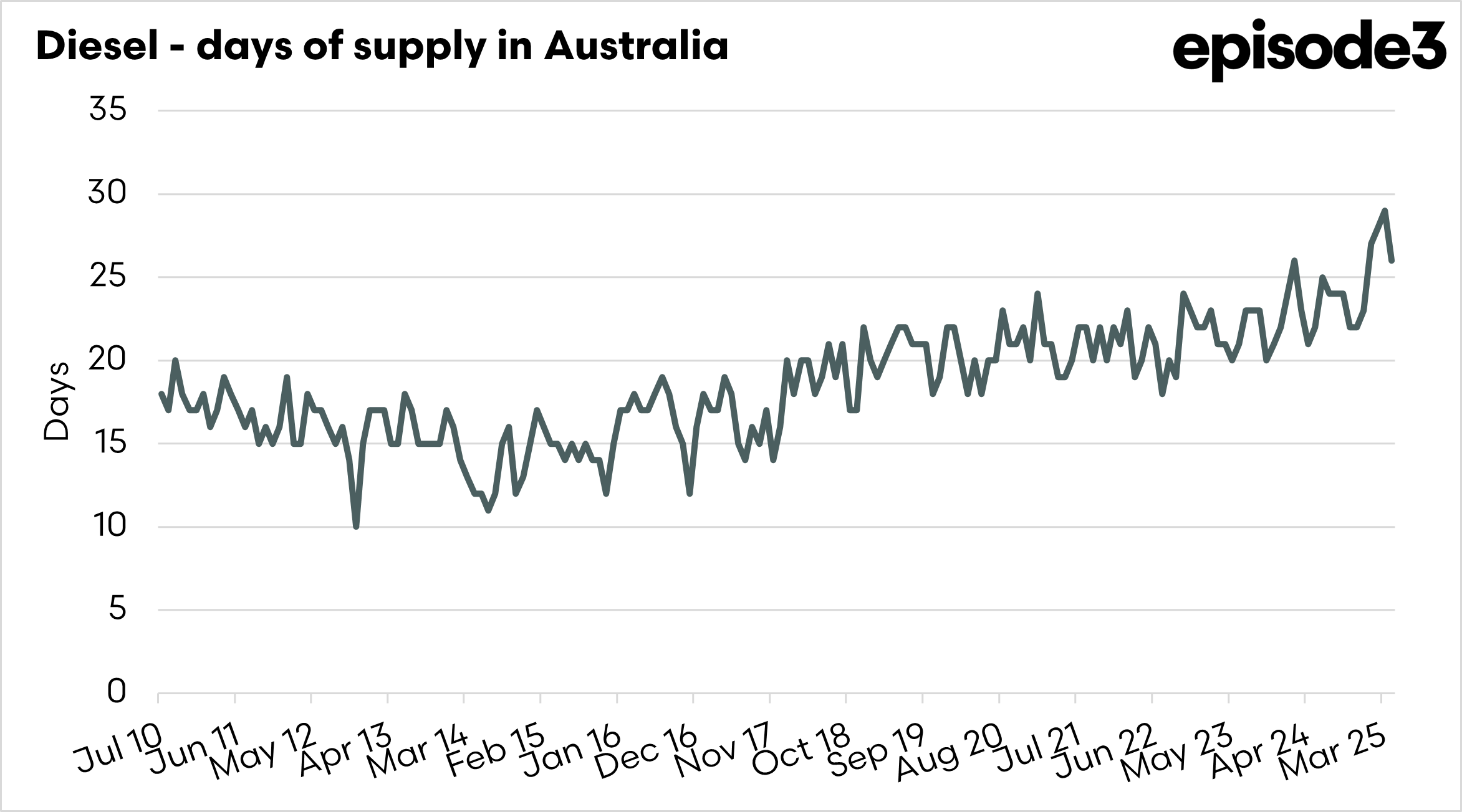

- The 26-day diesel figure is real but misleading, as it assumes imports stop and demand stays normal.

- A true fuel crisis would require a major, sustained disruption to imports such as war, blockade or cyberattack, which are low-probability events.

- In a disruption, demand would fall and local refining would continue, meaning supply could stretch to roughly six to eight weeks.

- The bigger risk is fuel allocation and timing, especially for agriculture during seeding and harvest, rather than total national stock levels.

- Increasing fuel reserves is possible but costly, and any large increase in storage would likely be paid for by taxpayers or consumers.

The Detail

Australia has 26 days of diesel supply, which sounds scary, and it is – but it’s not as bad as many may feel.

It is a statistic that gets repeated so often that it has taken on a life of its own. The number is used to suggest fragility and to imply the country is only a few weeks away from running dry. It makes for a strong headline. It is also only part of the story.

For fuel availability to become a genuine national issue, Australia would need to face a sustained disruption to imports rather than the routine volatility that occasionally affects prices. The scenarios most likely to cause that kind of disruption are severe: a major war that disrupts global trade routes, a naval blockade that restricts commercial shipping, or a large-scale cyberattack that affects ports, fuel terminals, or distribution systems.

All are low-probability events, but they are the types of shocks that could materially slow or halt the steady flow of tankers into Australia. In normal conditions, the country runs on a just-in-time fuel system. Ships arrive continuously, storage is relatively lean, and the economy functions smoothly. It is only if imports were constrained for weeks by conflict, blockade or a major cyber event that stock levels and fuel allocation would become a serious issue.

The 26-day figure itself is technically correct, but it is widely misunderstood. It reflects how long current fuel stocks would last if Australia continued to consume diesel at today’s normal rate and imports stopped entirely. For such an event to significantly impact our fuel supply, the local demand profile would have to change. We wouldn’t be going on long trips in the caravan.

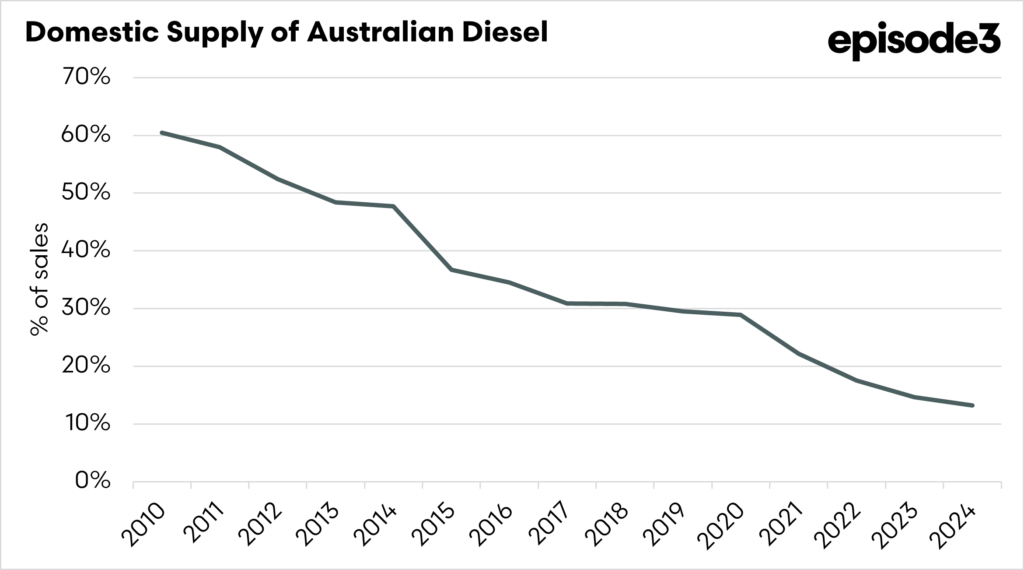

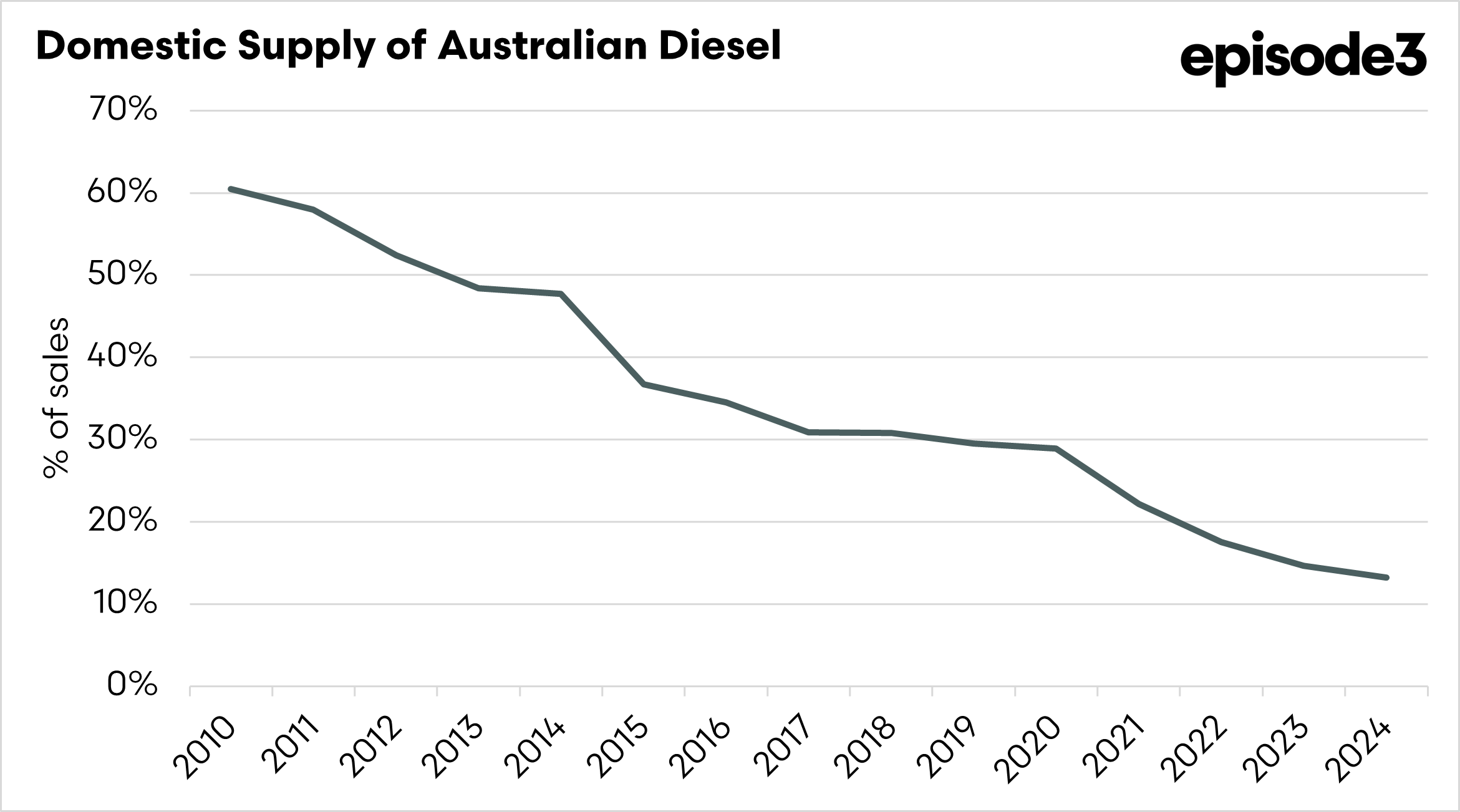

Demand would fall. Some of that decline would happen naturally as economic activity slowed. Some would come from deliberate rationing and prioritisation. Aviation would contract, discretionary travel would drop, construction activity would slow, and export-focused sectors would scale back. Domestic diesel production would also continue. Australia still refines fuel locally, even though refining capacity has declined significantly over the past decade. Output is lower than it once was, but it still provides a steady flow of supply. That means the system would not be running purely on stored fuel. Stocks would be drawn down, but production would still be adding to supply each day.

When those factors are combined, the headline number starts to look less like a deadline and more like a baseline. If imports stopped and demand remained unchanged, stocks would tighten rapidly. But that scenario is unrealistic. In a genuine disruption, demand would fall, and domestic production would continue. That stretches the timeline. If total diesel demand across the economy fell by 20 per cent and domestic production kept running, 26 days of supply could stretch to roughly 40 days. If demand fell by 30 per cent, the system might extend to around 47 days. If demand dropped by 40 per cent and production continued, availability could approach 58 days before severe constraints set in.

It is also important to recognise that relatively low stock coverage is not a new phenomenon. Australia has operated with modest fuel inventories for years. In the early to mid-2010s, the country often held closer to two weeks of supply rather than the three to four weeks seen more recently. In fact, the Albanese government have presided over the record stockpile.

That trend has seen rising stock levels across multiple governments and reflects structural changes. Low inventories are part of a just-in-time import model. In normal conditions, that model works efficiently. Fuel arrives continuously, storage is optimised, and the economy keeps moving. The vulnerability is relevant only if the flow of imports is disrupted for an extended period.

Even then, the probability of a severe and sustained disruption remains low. A scenario in which Australia loses access to imported fuel for weeks or months would imply much larger problems. Exports would fall, freight volumes would decline, mining output would contract, and economic activity would slow sharply. Fuel demand across the economy would drop simply because the economy itself was under stress. In that environment, the key question would not be whether Australia ran out of fuel after 26 days. The real issue would be how the remaining fuel was prioritised across a contracting economy.

This is where agriculture becomes central to the discussion. Farming does not consume the largest share of national diesel, but it is highly dependent on reliable access during specific windows, such as seeding and harvest. Even if national stocks could stretch toward six or seven weeks under reduced demand and ongoing production, fuel distribution and allocation would determine who actually receives the supply. Agriculture could face constraints sooner if priority shifts toward emergency services, freight, or other essential sectors. Timing matters more than total volume. Missing a seeding window because fuel deliveries are delayed has far greater consequences than the number of days shown in a national stock figure.

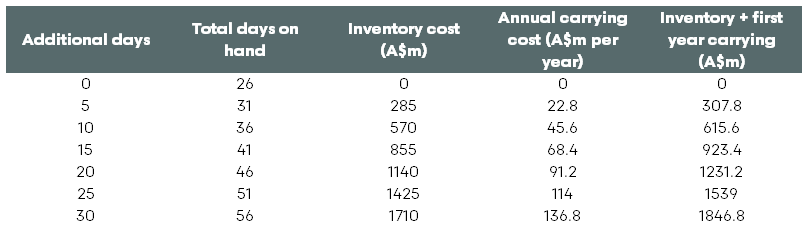

Calls to dramatically increase Australia’s fuel reserves are often touted as the solution. It sounds straightforward. Hold more fuel, and the problem disappears. In practice, building larger reserves comes with real, ongoing costs, and it is not one the private sector is likely to bear alone. Each additional day of diesel stock held nationally represents roughly A$55–60 million in fuel at wholesale value, excluding fuel excise. There is also a carrying cost. Financing, storage, insurance, and handling typically add costs; we have used an 8% carrying cost, which could be much higher if significant infrastructure investment is required.

Those costs accumulate quickly. Increasing national diesel coverage by five days would require roughly A$285 million in additional inventory and around A$23 million in carrying costs per year. Extending coverage by ten days would raise fuel costs to about A$570 million and annual holding costs to nearly A$46 million. Adding twenty days would push the capital requirement well beyond A$1 billion, with annual carrying costs approaching A$90 million. Commercial fuel suppliers operate on thin margins and optimise stocks for efficiency. They have little incentive to hold large additional reserves. If Australia wants significantly more fuel in storage, the cost will ultimately be borne by taxpayers, consumers or both. If the country wants more days of fuel, it will have to pay for them.

That does not mean additional reserves are unnecessary. It simply means the trade-offs should be understood. Holding more fuel provides insurance against low-probability but high-impact disruptions. Like any insurance policy, it comes at a cost. The question is not whether more fuel can be stored. The question is how much the taxpayer wants to pay for what is still a relatively low-risk scenario.

For agriculture, the more immediate question is allocation rather than total volume. Planning for low-probability but high-impact events is sensible. If Australia ever faced a disruption severe enough to restrict imports for an extended period, the economic shock would be far broader than the fuel issue alone. In that environment, governments would need clear plans to prioritise fuel use within agriculture. A practical approach would be to prioritise sectors that deliver the greatest calorie output for the domestic population. Not all agricultural production has the same impact on food security. In a constrained environment, ensuring that limited fuel supports the production and distribution of staple foods that provide the highest caloric value would help maintain stability.

Australia’s fuel position is not as fragile as the headline suggests, but it is not immune to risk either. The country operates on a just-in-time system that functions efficiently under normal conditions and can extend beyond expectations during a disruption. With a moderate reduction in demand and ongoing domestic production, the system could likely operate for about six to eight weeks before severe constraints emerge. The more relevant risk for agriculture is not that the nation suddenly runs out of fuel, but that access becomes tighter at the wrong time.

The real task for food security planning is to ensure that, in the unlikely event of a major disruption, limited fuel is directed where it delivers the most food for the population.