Australia’s Lentil Gold Rush Has a Limit

The Snapshot

- Lentils are attractive for both agronomic benefits and price, but recent price strength exists because the global market is small and supply has been tight.

- The lentil market rebalances through price falls, not rapid demand growth, making it highly sensitive to sudden increases in production.

- Record lentil production in Australia and Canada in 2025 has lifted global supply and is already weighing on prices.

- Individual expansion is rational, but collective expansion risks oversupplying the market and eroding the price that made lentils attractive.

The Detail

There is a new gold rush, and that’s in lentils. I’ve spent much of the past six months travelling around Australia and overseas, talking about grain markets, and lentils have been a consistent talking point. A gold rush can end with too many miners, and we could face a similar pattern in lentil production.

What has been striking is not simply the interest in the crop, but where that interest is coming from. Lentils have traditionally been grown in South Eastern Australia; they are now being seriously discussed in parts of Western Australia and even in central Queensland, where lentils were once considered too risky or agronomically marginal.

This shift is good; it provides new options to farmers, and more options are always good for diversifying income. Agronomy has improved, varieties are better adapted, and growers are under increasing pressure to find crops that deliver both rotational benefits and margin potential. Lentils fix nitrogen, provide a valuable disease break in cereal heavy systems, and add flexibility.

But agronomy is only part of the story. Price has also played a decisive role.

Over recent years, lentils have delivered returns that have caught the attention of growers well beyond their traditional production zones. That price signal is real, and it is rational for farmers to respond to it. The risk lies not in growing lentils, but in how many are grown, and how quickly production expands, particularly when major exporting countries are doing the same thing at the same time.

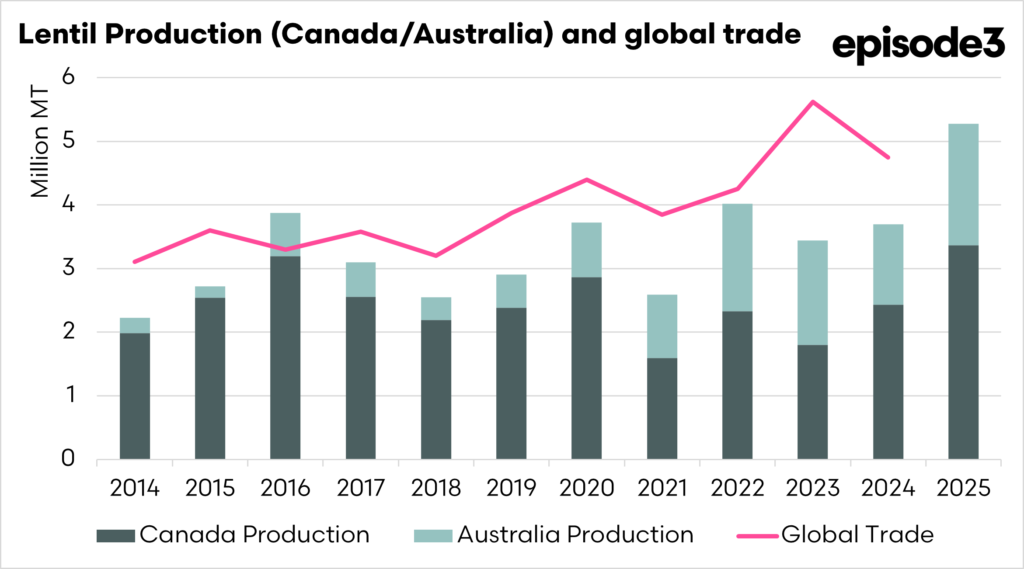

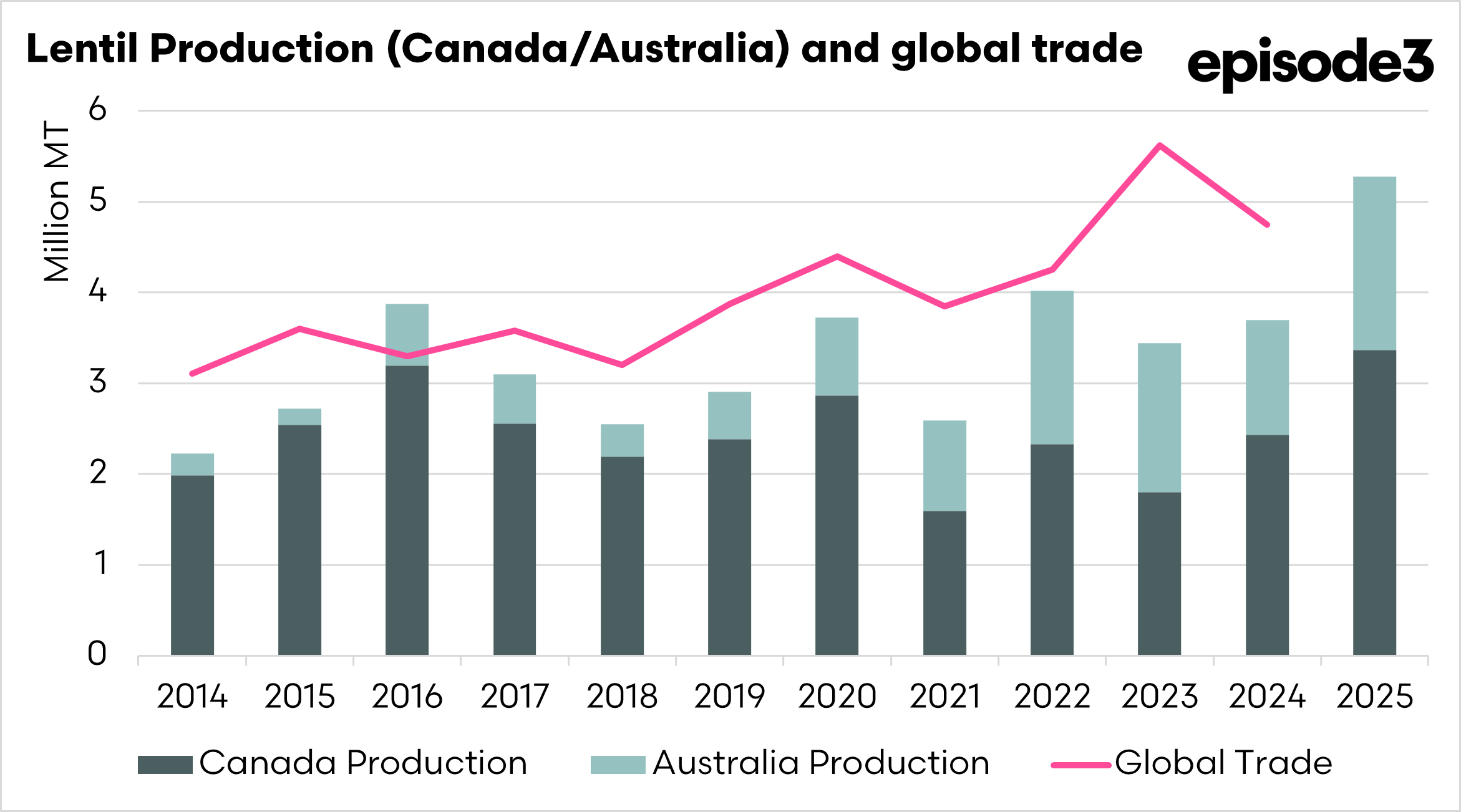

Despite being widely traded, lentils operate within a small global market. Over the past decade, annual global lentil exports have typically ranged between around 3.1 million tonnes and 4.4 million tonnes. For most years between 2014 and 2022, trade volumes sat comfortably within that band with a few notable exceptions.

In 2023, global lentil exports surged to approximately 5.6 million tonnes, before easing back to around 4.75 million tonnes in 2024. These swings matter because they show how little additional supply is required to push the lentil market beyond its normal operating range.

In grain market terms, this is a shallow market. Lentils simply do not have the depth to absorb rapid, large-scale increases in supply without a price response.

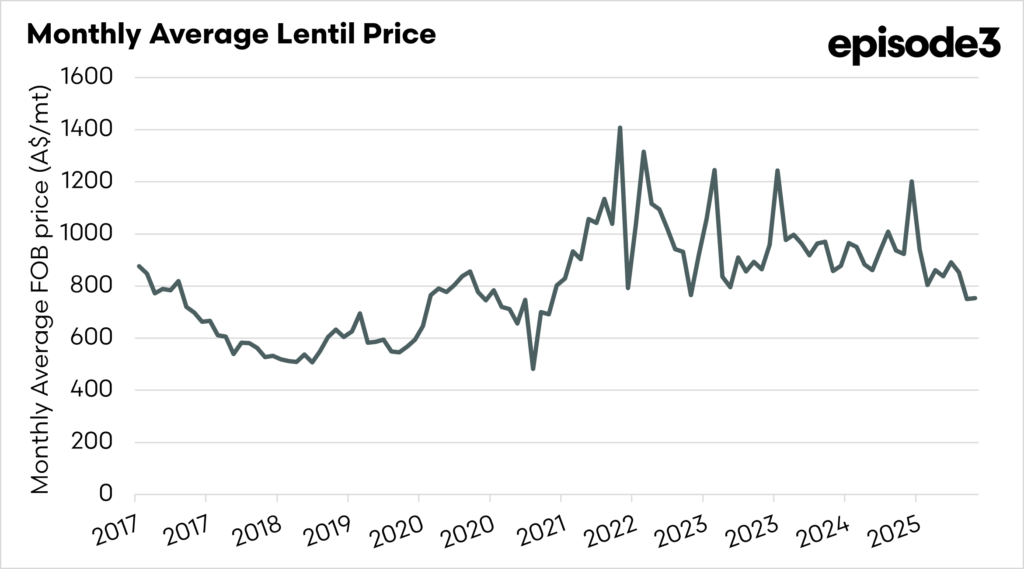

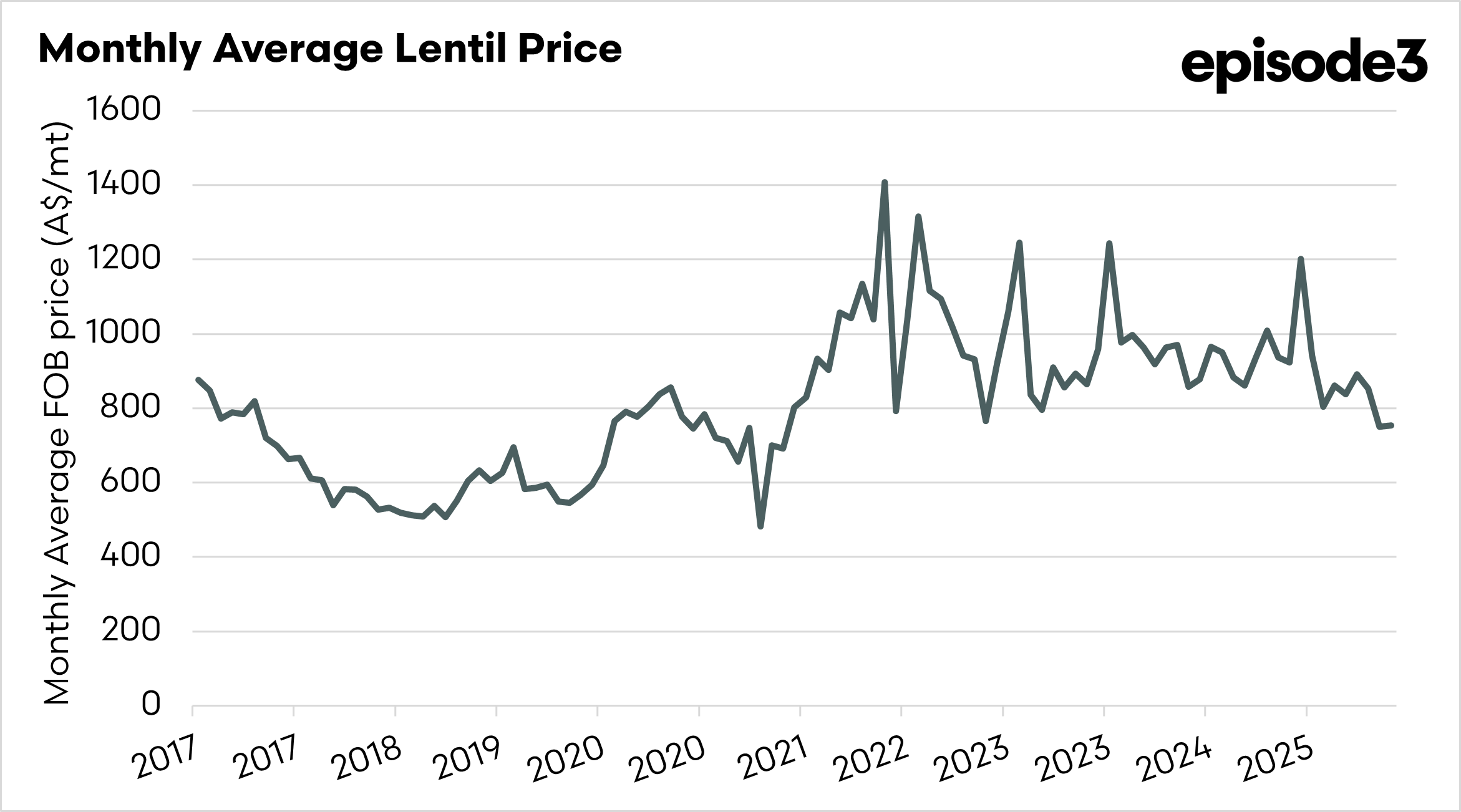

Australian lentil prices reflect this sensitivity very clearly. The monthly FOB data shows that lentil prices have been highly variable, moving sharply in response to changes in global supply.

In early 2017, Australian lentil prices were around A$850–880 per tonne. As global production expanded over the following two years, prices fell steadily. By late 2018 and into 2019, Australian prices had dropped to roughly A$520–600 per tonne.

That decline of around 35 to 40 per cent did not occur because demand collapsed. During that period, global lentil exports remained relatively steady, averaging 3.2-3.9 million tonnes. Prices fell because supply outpaced the market’s ability to absorb it.

The reverse is also evident in the data. During periods of tight supply and disruption between 2020 and 2022, Australian lentil prices surged. Prices commonly traded between A$800 and A$1,000 per tonne, with peaks exceeding A$1,300 per tonne in early 2022.

These extremes are a key point for growers to understand: lentil prices are not stable. They respond quickly and decisively to changes in supply.

At its core, the lentil market works like most agricultural markets, but with one important difference: it is small.

Demand for lentils grows steadily but slowly, driven by population growth and gradual dietary changes. It does not jump sharply from one year to the next. People do not suddenly eat much more lentils just because prices fall.

Australia and Canada can add large volumes of lentils in a single season if prices are attractive and conditions are favourable. When that happens, more lentils enter the global market than buyers planned to purchase at existing prices.

When supply outpaces demand, the market has only one practical way to rebalance: prices fall. Lower prices encourage buyers to purchase more and help stocks clear.

This is why lentil prices tend to move sharply rather than gradually. In a small market, it does not take much additional supply to tip the balance. A few hundred thousand extra tonnes globally could be enough to materially shift prices.

Strong prices, in other words, are not guaranteed by demand alone. They exist because supply has, at times, been constrained. If supply expands too fast, prices adjust downwards to restore balance.

Record supply is already testing the market, and that dynamic has become particularly relevant in 2025.

Both Australia and Canada have achieved record lentil production this year. Australian output has reached new highs as the area continues to expand and yields hold up. At the same time, Canadian production rebounded strongly, exceeding 3.3 million tonnes.

Taken together, these two countries have delivered a substantial increase in global lentil availability in a single season. In a market where normal global trade sits around four million tonnes, this additional supply is not marginal.

The pricing response has been evident. Australian lentil prices through late 2024 and into 2025 have generally softened relative to earlier peaks, trading mostly in the A$750–950 per tonne range, with periods below that level. This is well below the extremes seen in 2021–22 and reflects a market that is becoming more comfortably supplied.

From an individual farm perspective, the decision to grow lentils is often entirely rational. The agronomic benefits are real, and the recent price history includes periods of exceptional returns. One grower expanding their lentil area does not move the market.

The risk arises when many growers across multiple regions and countries reach the same conclusion simultaneously.

As lentils expand into new production zones in Australia, the national supply becomes more resilient and better able to produce large crops simultaneously. When this coincides with strong production in Canada, the world’s largest exporter, global supply can rise quickly.

In a small market, that collective response is what drives price corrections.

This article is not an argument against lentil production in Australia; this article is a warning about pace and scale, not participation.

Record production in Australia and Canada in 2025 has already shown how quickly the lentil market can move from tight to oversupplied. History suggests that once this shift occurs, prices adjust decisively rather than gradually.

For growers considering lentils, the key question is no longer whether they can be grown in more places. The more important question is whether the global market can absorb the contemplated volume without a significant price reset.

If you are growing lentils, don’t budget based on high prices; budget conservatively and account for the agronomic benefits of growing them.

In lentils, the data is clear. Strong prices are a reward for scarcity. Remove that scarcity too quickly, and the reward disappears just as fast.