Market Morsel: Wheat prices positioned for a boom

Market Morsel

Supply and demand are what drive grain prices, but in reality, supply has the biggest impact on price. We are in a time when prices of grains could feasibly boom to extreme levels. Why do I think they could boom? Because the world is getting short of wheat and corn.

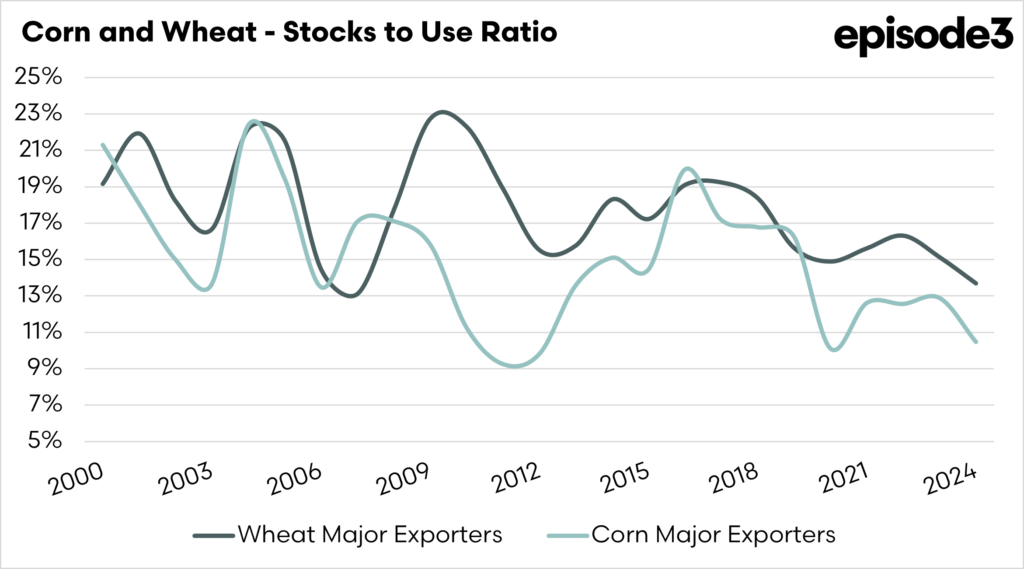

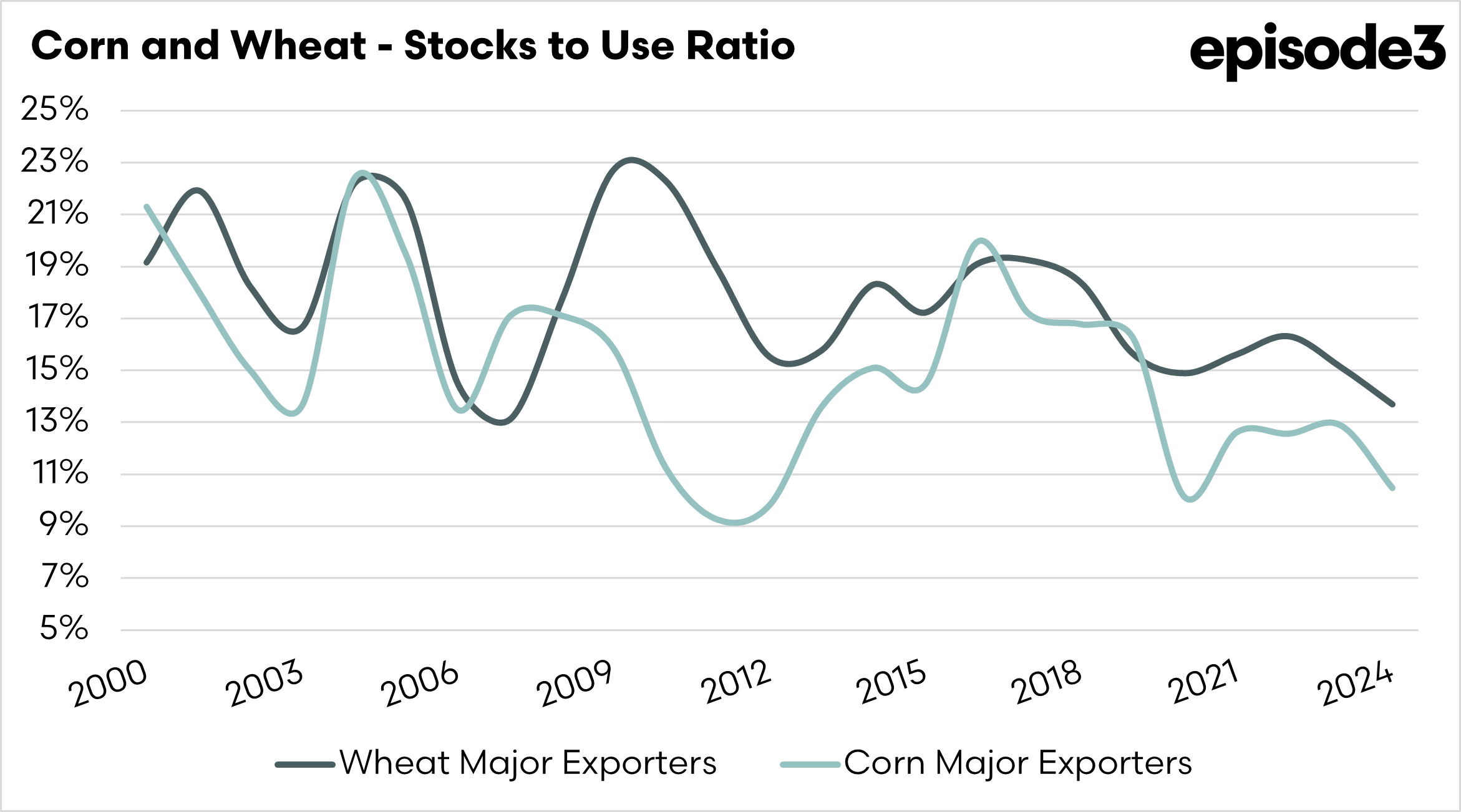

The stocks-to-use ratio is a handy way to understand how tight or plentiful grain supplies are in any given year. It compares two key figures: how much grain is expected to be left over at the end of the season and how much is expected to be used over the course of the year, either through local consumption or exports. This number is usually shown as a percentage and helps people working in agriculture—like farmers, grain traders, and food companies—gauge how balanced the supply and demand is.

When the stocks-to-use ratio is low, it means that most of the available grain is being used up, with not much left over. That can make the market nervous, especially if there’s a risk of poor weather or a smaller harvest next season. In these cases, grain prices often rise because buyers want to secure supply while they still can. On the other hand, a high stock-to-use ratio means plenty of grain is stored compared to how much is used. That can help keep prices steady or even push them down, as there’s less urgency for buyers and more comfort in knowing supply is secure.

Because it’s such a useful indicator of supply pressure, analysts, policymakers, and everyone involved in the grain supply chain closely watch the stocks-to-use ratio. It’s one of the best ways to quickly understand whether grain markets will likely be calm or volatile.

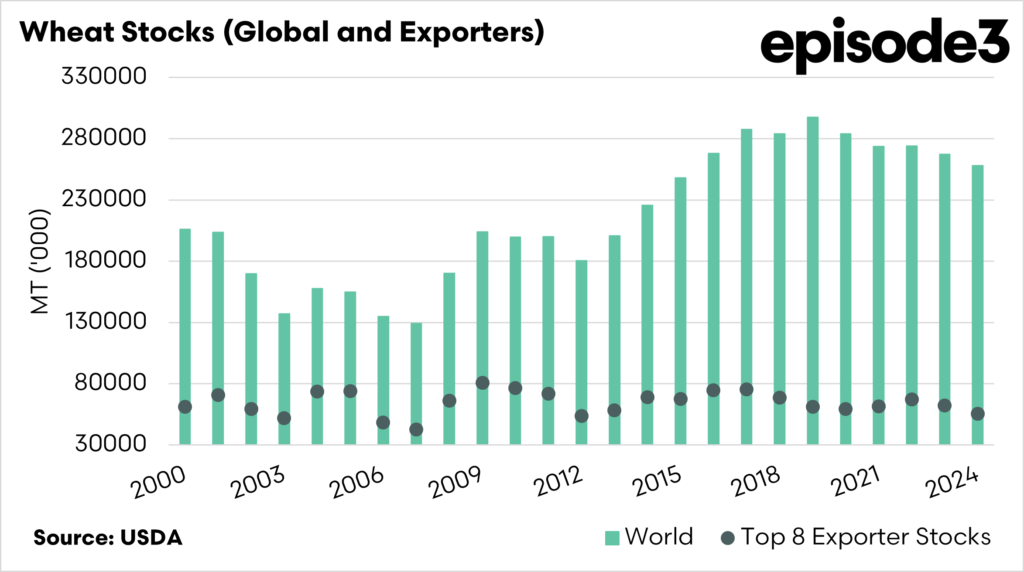

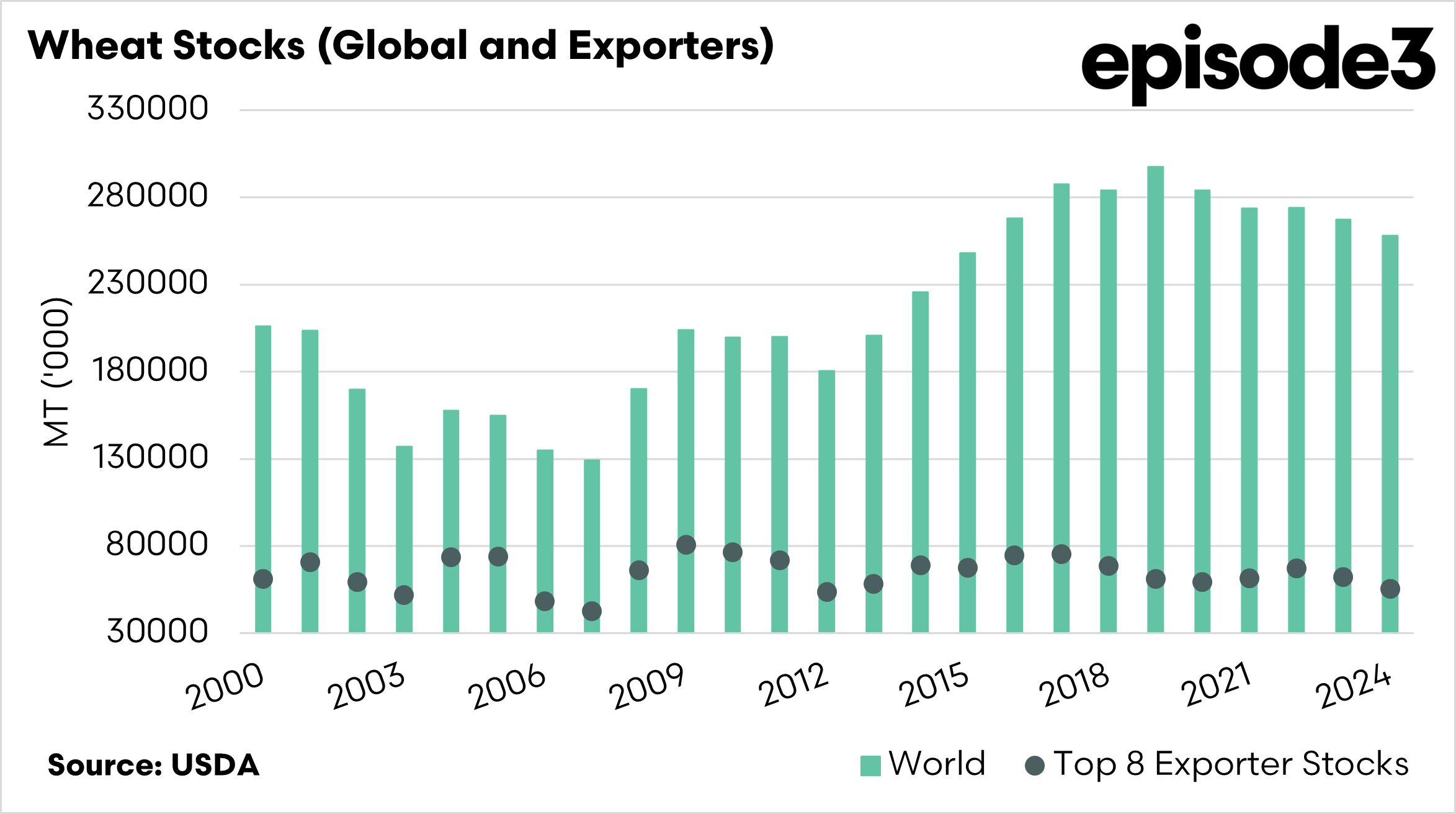

While the global stocks-to-use ratio gives a broad picture of supply and demand, it’s often more important to focus on the stocks-to-use ratio of the major exporting countries. That’s because these exporters, such as the United States, Canada, Australia, Russia, Ukraine, and Brazil, are the main suppliers to international grain markets. Their stocks are the ones that actually move across borders and help meet global demand, especially when countries that rely on imports face shortfalls.

A country might have high grain stocks, but if it doesn’t typically export grain or if those stocks are tied up for domestic use, they don’t help ease shortages in the world market. In contrast, if exporter stocks are low, it can cause real concern for food-importing nations. When major exporters hold less grain in reserve, global buyers have fewer options, and prices tend to rise faster and more sharply. This is especially true in tight years when even small disruptions like droughts, geopolitical tensions, or shipping issues can lead to big market reactions.

In short, the stocks-to-use ratio of exporting countries gives a more accurate signal of how much grain is actually available to the world. It, therefore, has a much more significant influence on international prices and food security than the global ratio alone.

So, let’s look at the stocks-to-use ratio of the leading exporters of corn and wheat. The chart below shows that the corn stu is at its lowest since 2020, and before that, 2012. Whilst wheat is at the lowest stu since 2007.

This means that wheat and corn, both commodities that are replaceable with one another, have very low stock-to-use ratios. If there are any issues, and a few are rising with production around the world, then we could see a shortage of supply and a big bump in pricing. Fingers crossed!