Rice Adds to the Grain Glut, Weighing on Wheat Prices

The Snapshot

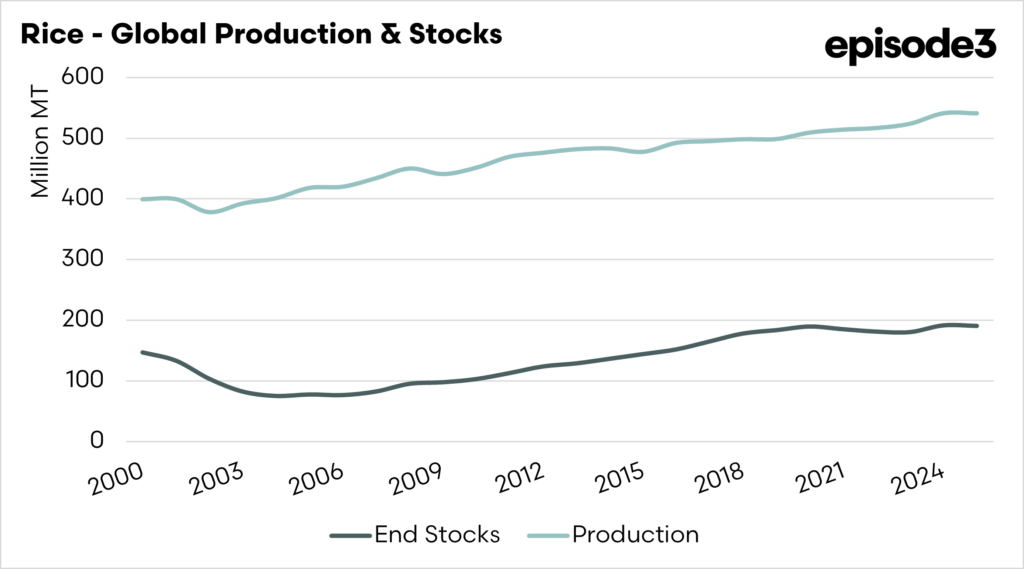

- Global rice production reached 541 million tonnes in 2025, only marginally below the 2024 record, up from around 400 million tonnes in the early 2000s.

- Global ending rice stocks have rebuilt to around 190 million tonnes, compared with less than 100 million tonnes in the mid-2000s.

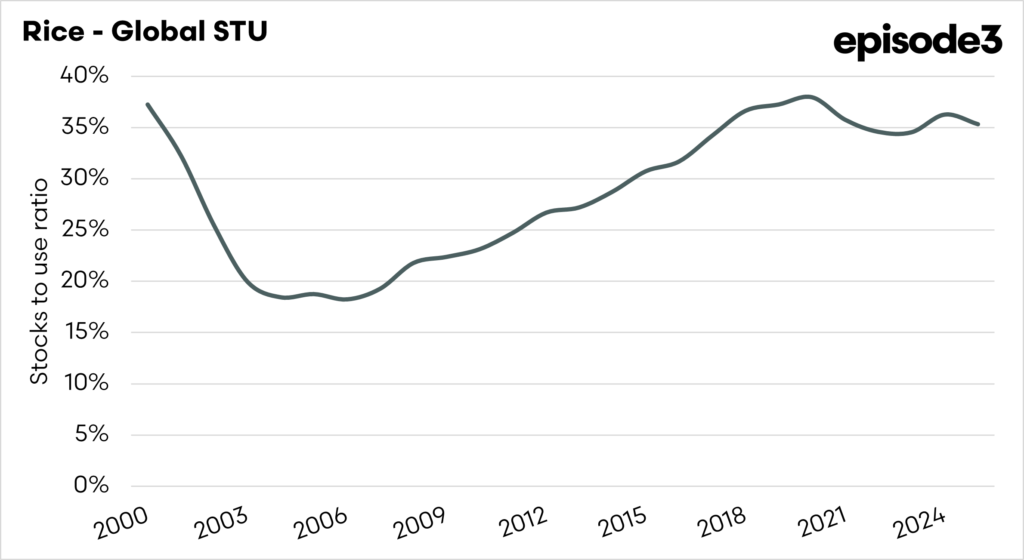

- The global rice stocks-to-use ratio is about 35%, indicating a very comfortable supply position by historical standards.

- Rice export volumes have more than doubled since the early 2000s, increasing the flow of surplus grain into global markets.

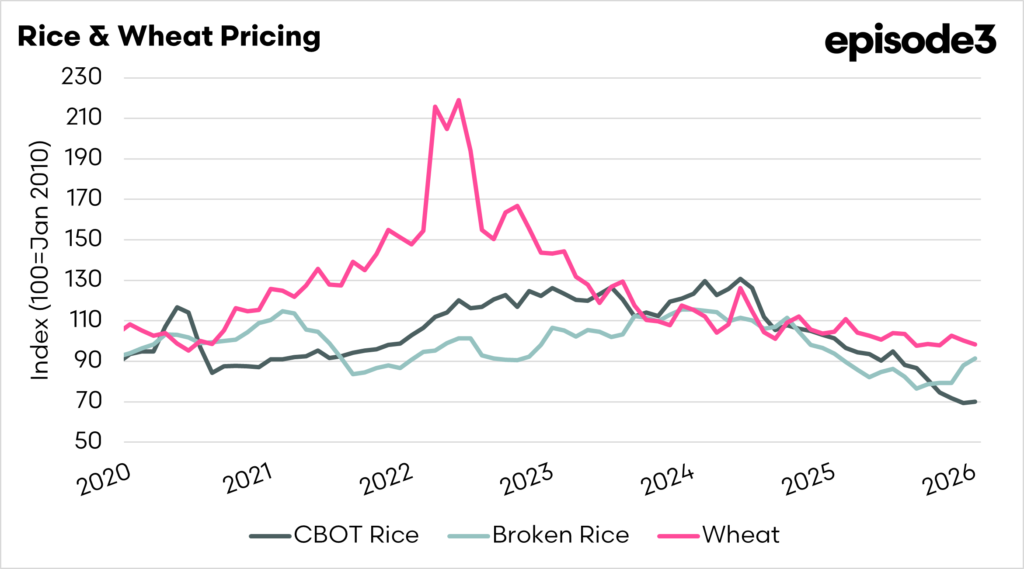

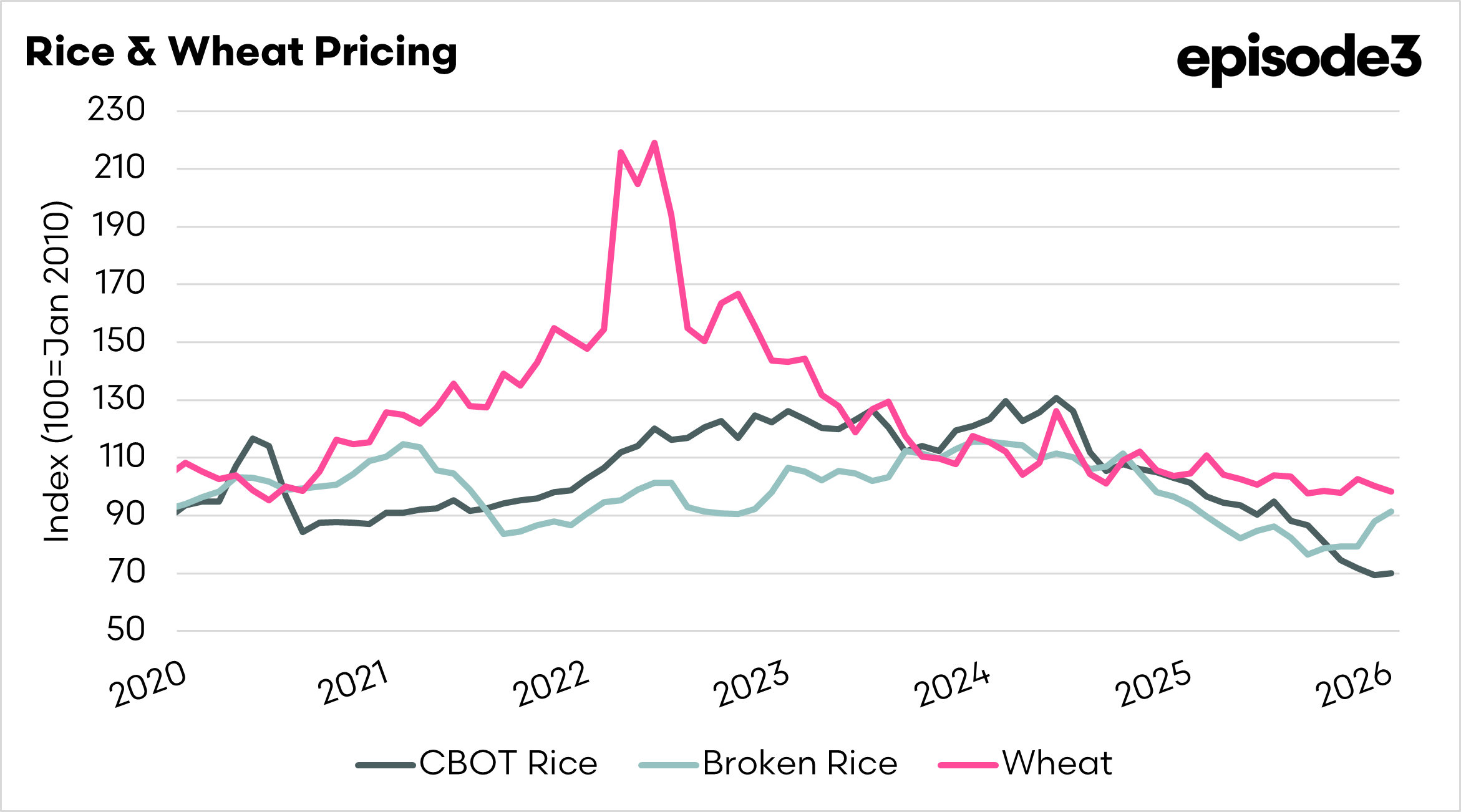

- Abundant supplies of lower-grade and broken rice are increasingly substituting for feed wheat and barley, adding to downward pressure on wheat prices within the broader grain glut.

The Detail

The rice market is not regularly covered in Australian agricultural media, but it has a wider impact beyond rice producers. The fate of rice affects grain producers, and the world is producing record volumes of rice.

Global rice production has increased steadily in recent years, adding another layer to the broader surplus developing across global grain markets. Favourable seasonal conditions across much of Asia, combined with incremental improvements in yields and continued government support for staple food production, have lifted output to record or near-record levels. Large producers such as India, China and several Southeast Asian nations have prioritised rice self-sufficiency, ensuring planted area has remained resilient even as prices softened. In some regions, improved irrigation, seed technology and input availability have further supported production growth.

This expansion in rice supply matters beyond the rice market itself. As output has grown faster than consumption in several exporting nations, export surpluses have increased, exerting downward pressure on prices and intensifying competition in import markets. For feed and food buyers, abundant rice can serve as a substitute or a marginal price anchor relative to other grains.

Record rice production is reinforcing the broader grain glut, adding weight to global balance sheets, and limiting the scope for sustained price recovery across the complex.

The world produced 541mmt of rice in 2025, only slightly lower than the previous record in 2024. Production has increased significantly since the turn of the century, when 400mmt of rice was produced.

At the same time, consumption has also increased, but not fast enough to prevent a gradual rebuilding of stocks. Global ending stocks have risen from <100mmt in the mid-2000s to 190mmt in recent years, even as exports have expanded sharply. Export volumes have more than doubled since the early 2000s, underscoring that rising production in key suppliers has led to larger surpluses entering global markets. This combination of higher yields, resilient production and expanding stocks underscores why rice has increasingly contributed to the broader grain glut, adding weight to global balance sheets and acting as a quiet but important influence on price dynamics across the wider grains complex.

This stockpiling can be observed in the stocks-to-use ratio for rice. The stocks-to-use ratio measures the extent to which rice is held in reserve relative to total annual consumption, providing an indicator of market tightness or sufficiency. A higher ratio indicates a more comfortable supply and lower price risk, whereas a lower ratio signals tighter availability and greater sensitivity to production shocks.

Globally, the current STU is 35%, meaning that if no rice were produced, 35% of annual demand could be met from stockpiles. This indicates a well-supplied environment for rice and another grain commodity, with high stocks and production.

Feed substitution is one of the key channels through which rice influences the broader grains complex. When rice supplies are abundant and prices soften, lower-grade and broken rice increasingly enter feed rations, particularly in regions of Asia. This creates competition for feed wheat and barley, reducing demand when price relationships favour rice.

The rise in global rice stocks in recent years is another factor contributing to the current global grain glut. Whilst there is no one-for-one relationship between wheat and rice, they do have an impact within the wider grains complex.