Sorghum: Brazil is now a competitor for Australia.

The Snapshot

-

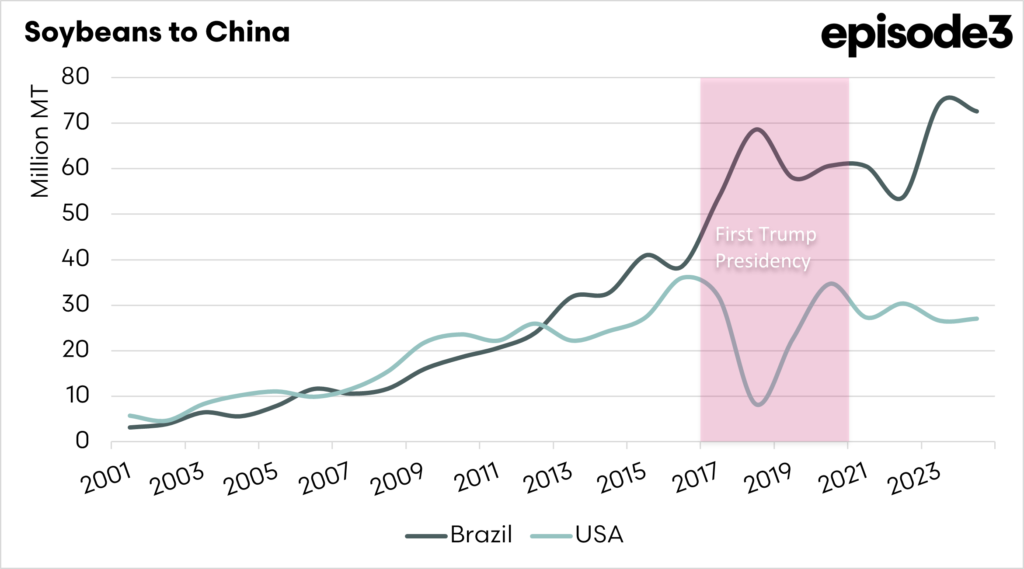

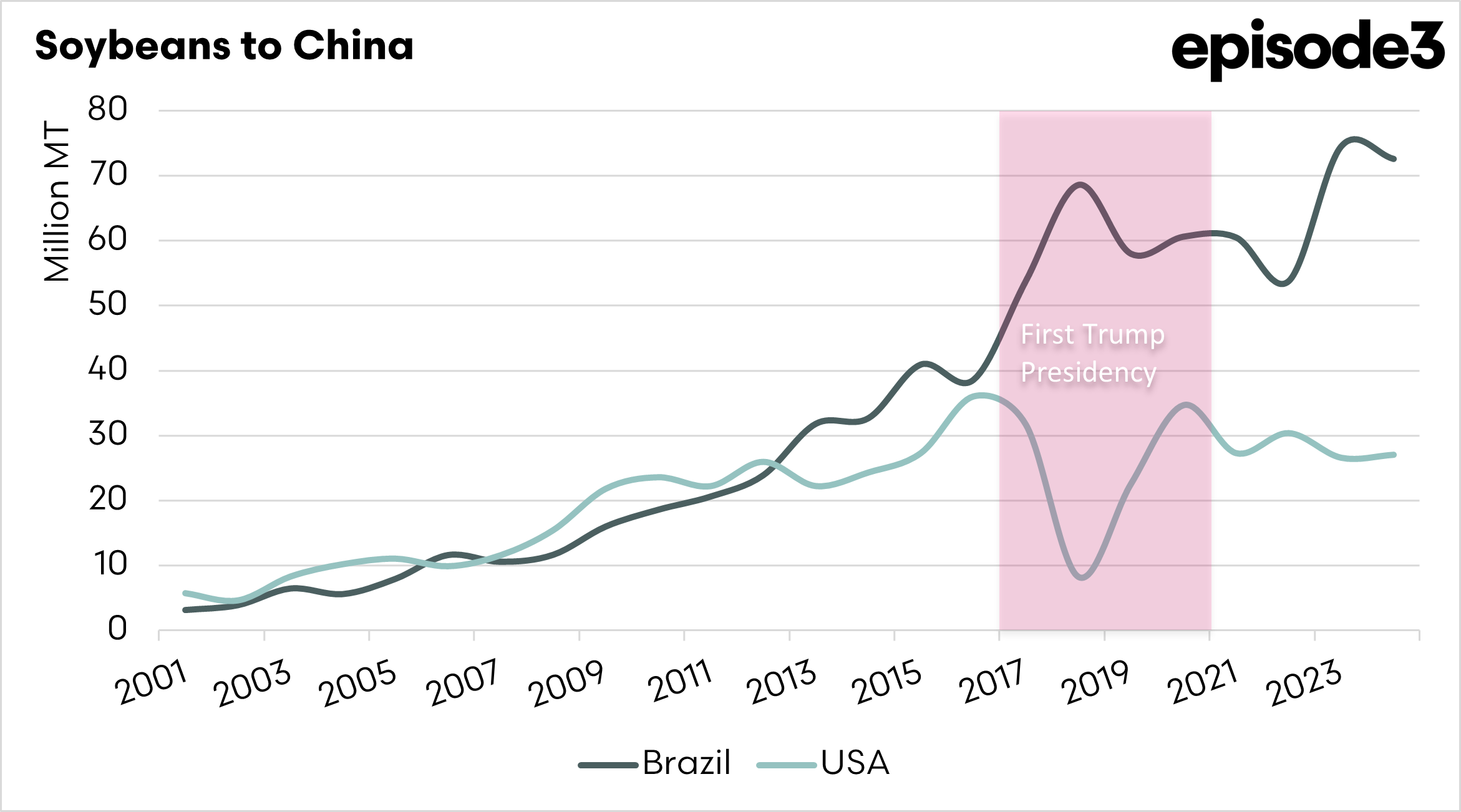

China’s approval of Brazilian sorghum imports mirrors the earlier soybean shift, where Beijing redirected purchases away from the US during Trump’s first term and entrenched Brazil as its dominant supplier.

-

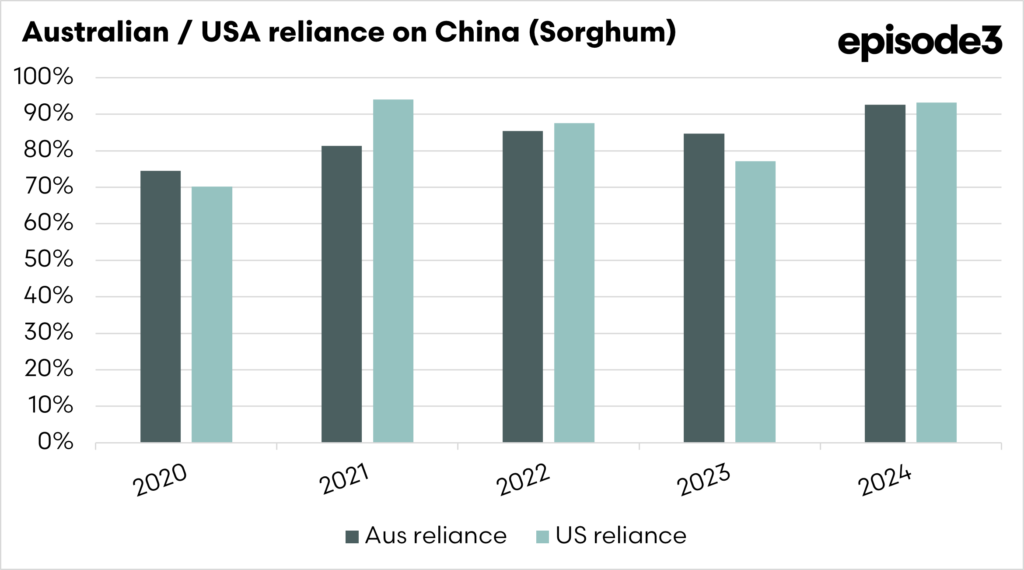

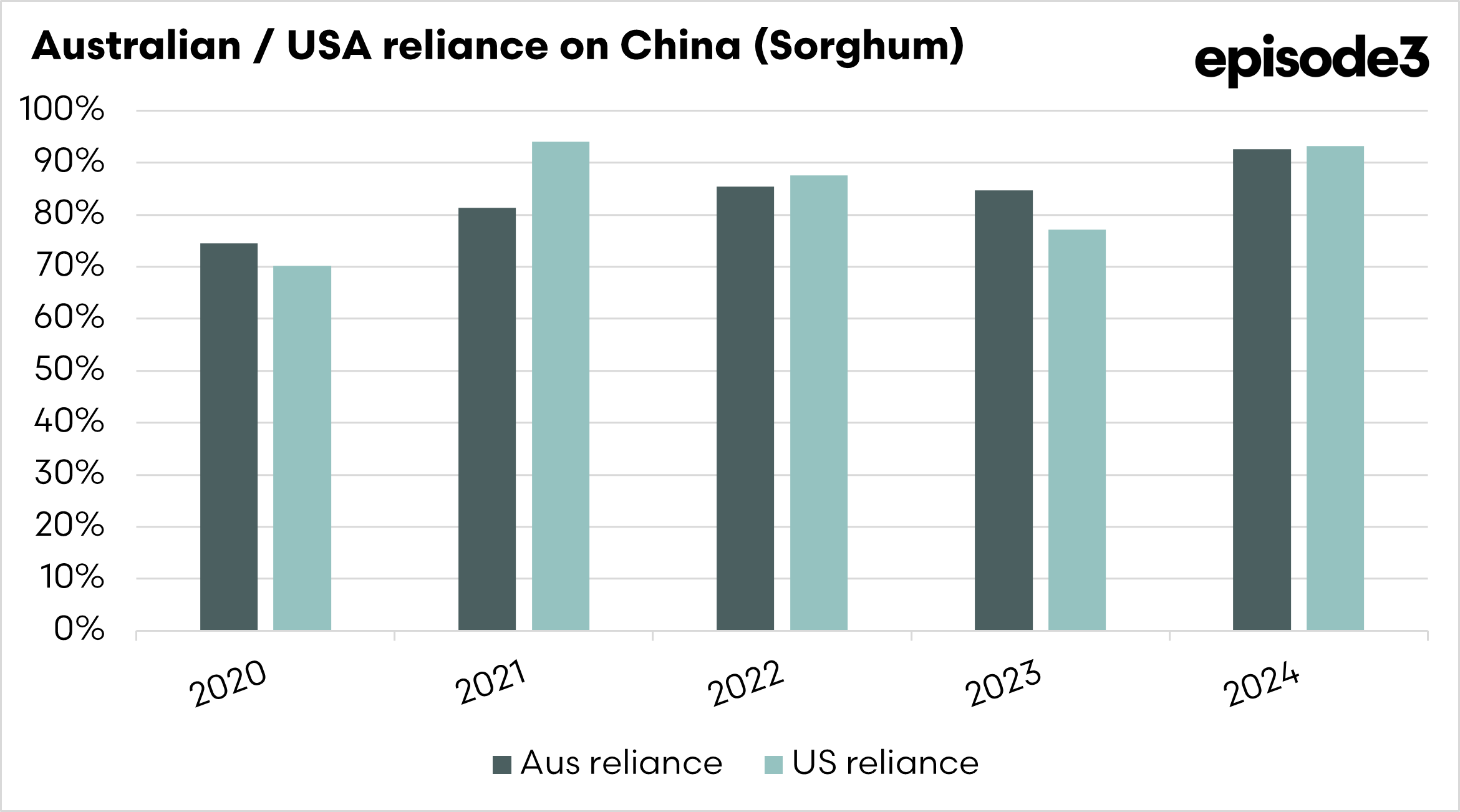

US sorghum is highly exposed, with over 80% of exports usually going to China; volumes have already collapsed from 5.5 million tonnes in 2024 to just 1 million tonnes so far in 2025.

-

Australia also relies on China for more than 80% of its sorghum exports, leaving growers vulnerable to any shift in Chinese buying patterns.

-

Brazil’s sorghum exports were historically small and domestically focused, but with land, infrastructure, and political support, production and exports could expand rapidly, creating lasting supply chains.

-

In the short term, Australia gains from US losses, but in the long term, Brazil’s rise could erode its competitive edge, risking stranded surplus and weaker basis levels given the lack of alternative markets.

The Detail

China’s green light for Brazilian sorghum imports marks the latest pivot in global grain trade, echoing the seismic shift that redefined the soybean market a decade ago. For US and Australian growers, the move is both a warning and a wake-up call

Over the past decade, China has steadily deepened its trade ties with Brazil in grains and oilseeds, reshaping global flows in the process. The turning point came during the first Trump administration, when Beijing retaliated against U.S. tariffs by sharply reducing soybean purchases from American farmers and shifting its buying power toward Brazil. That move not only met China’s immediate feed demand but also cemented Brazil as its dominant soybean supplier, with investments in logistics, port capacity, and long-term contracts reinforcing the relationship.

The recent approval of Brazilian sorghum exports to China is a natural extension of this strategy, demonstrating Beijing’s preference for broadening supply chains with Brazil as a trusted, large-scale partner in feed grains and oilseeds.

Prior to the first Trump administration, the US and Brazil used to export similar volumes; in recent years, however, Brazil has seen a significant increase in exports to China. China has been attempting to protect itself from the potential risks of reliance on the US as a trade partner. They are now set to do the same with sorghum.

The US is heavily reliant on China as a market for sorghum, and this move by China is a significant concern for US producers. On average, more than 80% of US sorghum exports are destined for China; however, in 2025, we saw a significant drop in purchases by China. In 2024, they purchased over 5.5 million tonnes of sorghum from the US, but so far this year, they have only purchased 1 million tonnes.

Australia is similarly reliant on China as a market for sorghum, with exports regularly exceeding 80%. Is China’s move a risk or an opportunity for Australian producers?

Until very recently, most of Brazil’s sorghum was used domestically, especially as a cheaper feed alternative in its poultry and pork industries or as a rotation crop in drier regions. Brazilian Exports are limited and inconsistent, often a few hundred thousand tonnes at most.

Through opening a door for Brazil, China signals that it does not want to be dependent on any single supplier. Brazil has the land, climate, and infrastructure to rapidly scale up sorghum production in a similar manner to how it expanded soybean production after the first Trump administration’s tariffs. Once China invests in new Brazilian supply chains, those flows may become “sticky,” even if political conditions change.

Currently, Australia is in a favourable position, as purchases from the US are declining, and Brazil is not yet ready to capture the entire market. We are likely to remain a strong supplier, alongside a growing Brazil. However, in the longer term, this may change.

For Australian growers, this could result in Australia moving from being a supplier of choice to China to having a stranded surplus. A shift in Chinese buying preferences, whether triggered by politics, price competitiveness, or logistical convenience, would immediately squeeze Australian basis levels, given the lack of alternative markets deep enough to absorb current export volumes. In short, Brazil’s entry erodes Australia’s competitive edge and exposes producers to the very real risk of being displaced in their single most important market.

When China blocked Australian barley in 2020, growers managed to redirect exports to Saudi Arabia and other markets, but only at lower prices. Sorghum does not have the same depth of alternatives, making reliance on China far riskier.

In the short to medium term, Australia should benefit from the losses of the US in its trade war with China. However, Brazil’s entry into the market suggests that China’s reliance on a single supplier is fleeting. Unless Australia diversifies its outlets or secures long-term stability in its relationship with China, today’s strength could become tomorrow’s vulnerability.