Why isn’t Canola A$1000 per tonne?

The Snapshot

- We have had a lot of conversations with farmers who are surprised that canola is not above $1000 per tonne, like recent years.

- The highs of recent years were caused by a combination of factors.

- Canada had a bad drought; they are the world’s largest exporter.

- Ukraine had a war; they are the world’s third-largest exporter.

- Energy prices were high, and that correlates with the oilseed complex.

- Avoid anyone who says ‘this is the new norm’. Commodity markets tend to cycle.

- Remember high prices are the cure for high prices, and vice versa.

- Canola prices are still historically high.

The Detail

Why isn’t canola A$1000 per tonne is a question I have been receiving a lot recently. So I thought I’d have a look at the question and also have a look at what is happening in the canola space.

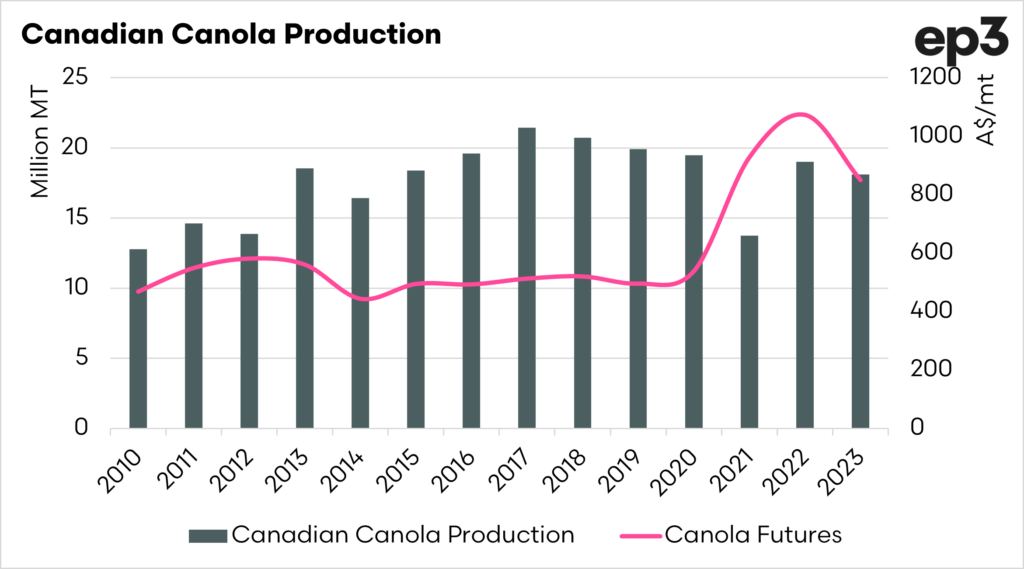

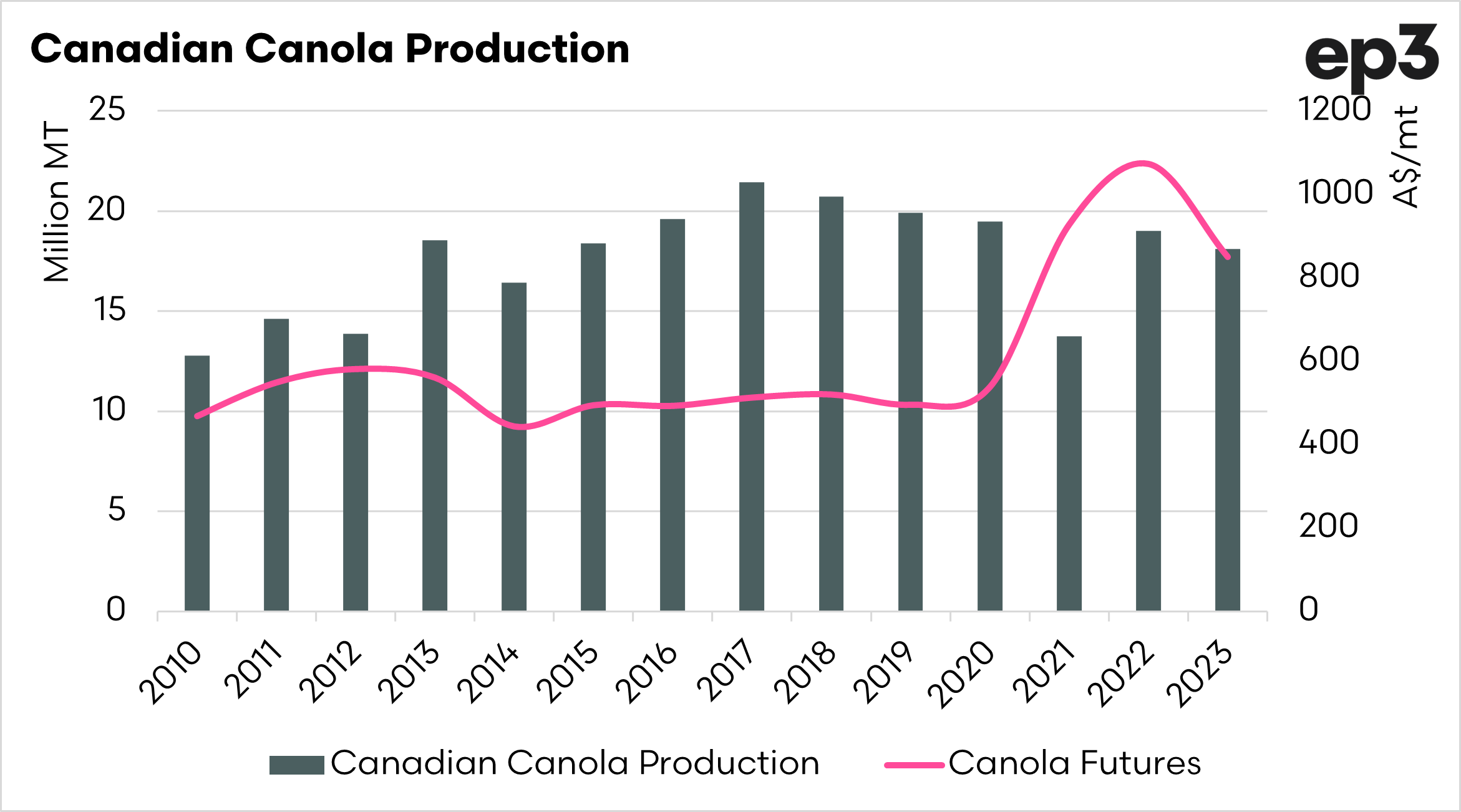

Firstly, let’s look at why canola got so high in recent years. It was all down to our friends in Canada. They had a dreadful drought in 2021, which resulted in their production falling to extremely low levels, and struggling to meet their domestic demand, never mind having an export surplus.

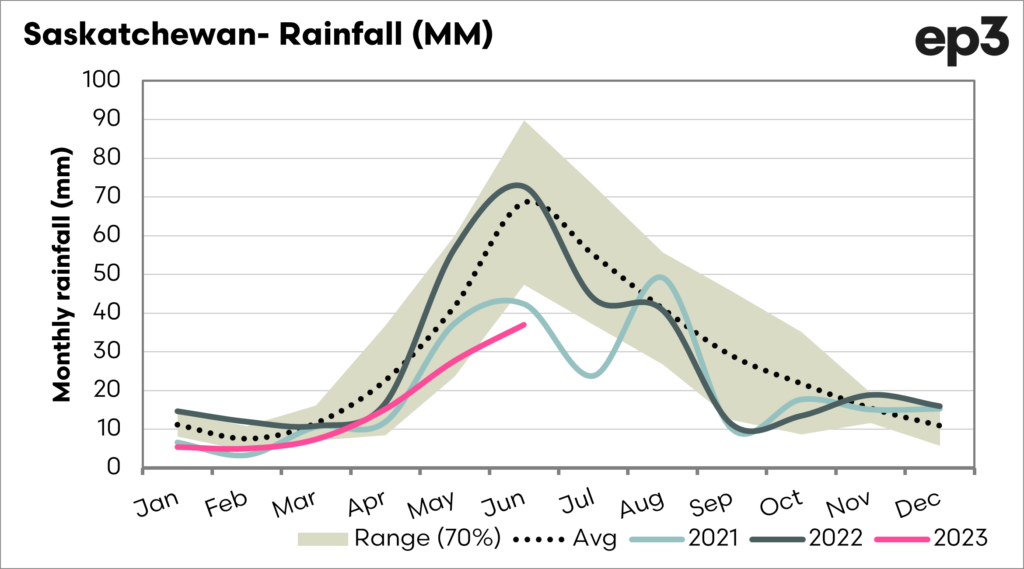

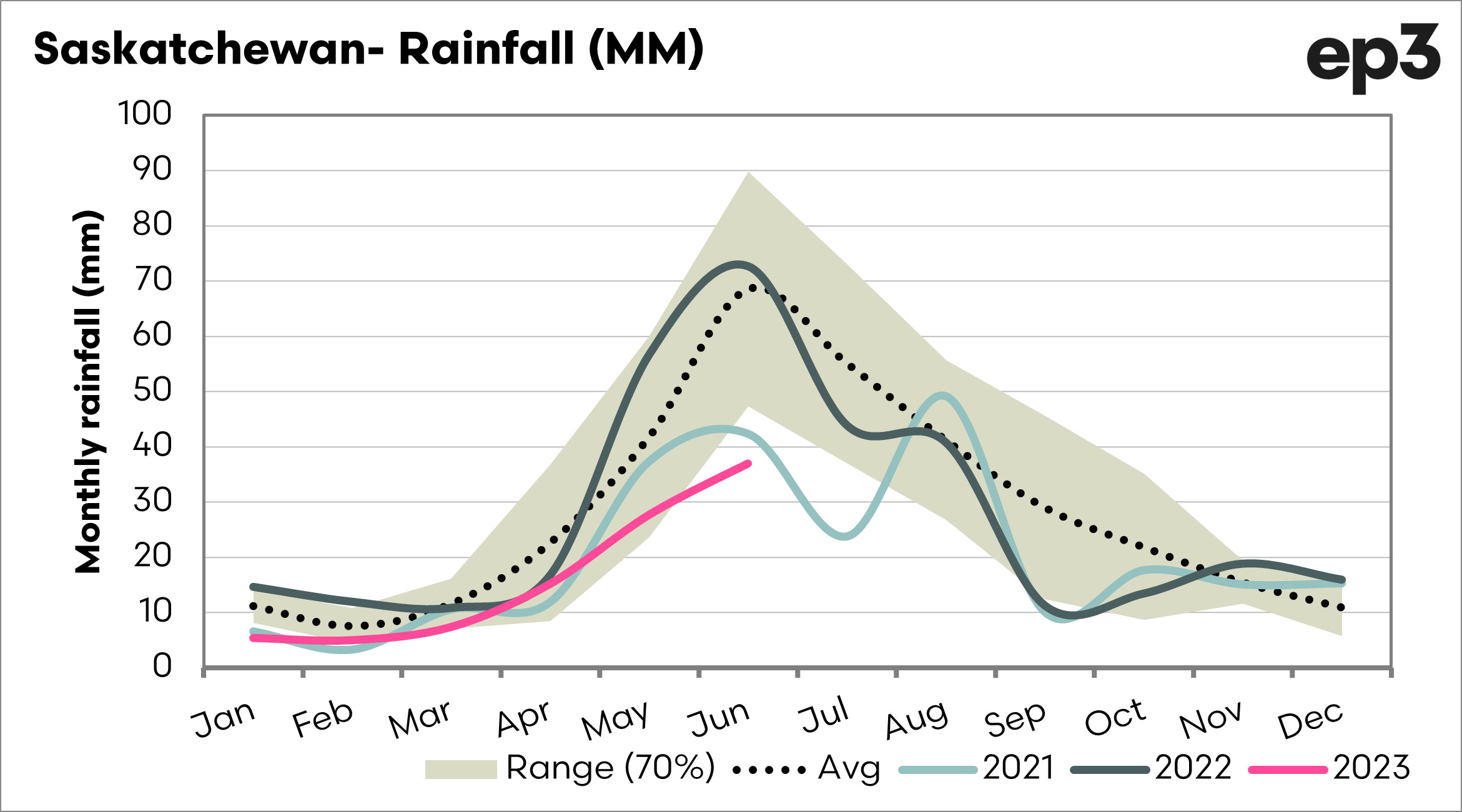

When we look at Canada, the bulk of the Canola crop is produced in the difficult-to-pronounce province of Saskatchewan.

The season started off reasonably well for them, with forecasts of large crops. However, the rainfall in this critical period has been below the standard deviation.

This year production in Canada is set to decline year on year, with forecasts of 18.1mmt. This will give Canada a strong surplus for exports.

This will help reduce global supplies of canola as their crop is downgraded.

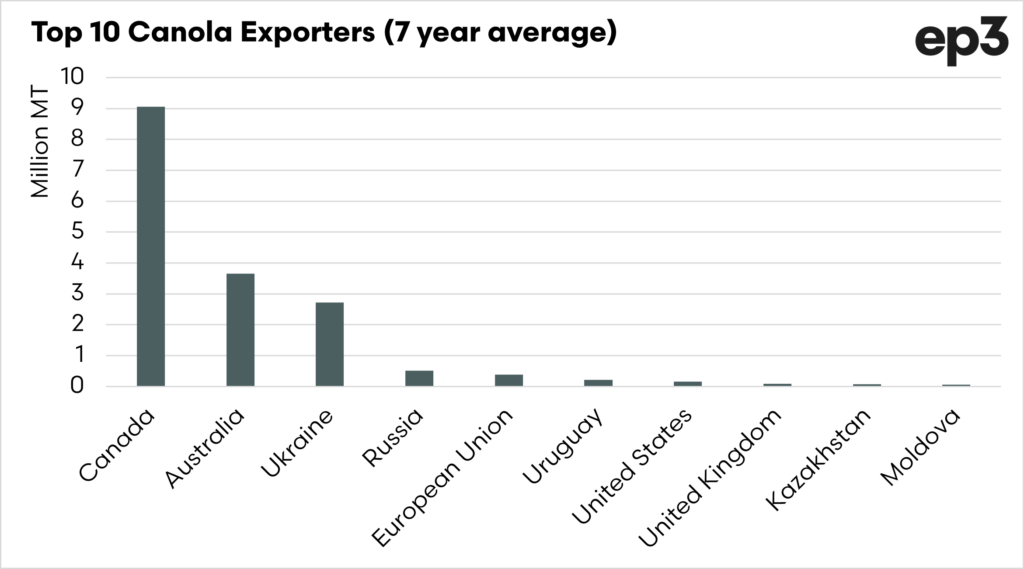

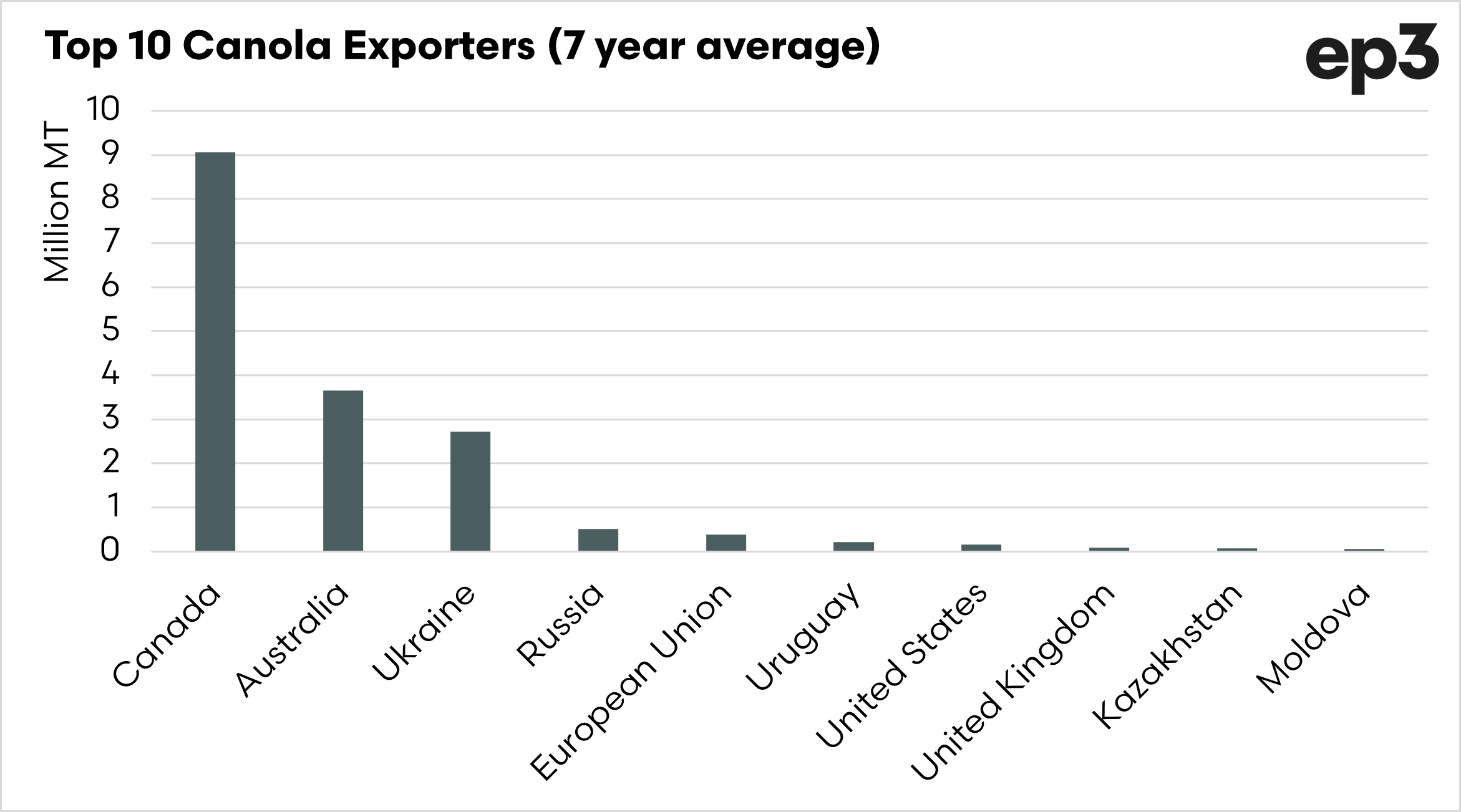

Let’s look at it in a little more detail because in recent years it hasn’t just been Canada facing turmoil. The chart below shows the top ten canola exporters (based on 7 year average). As we can see in this chart, Canada is dominant, with Ukraine and Australia following behind. The rest are largely rats and mice.

While Canada had a reduced surplus for exports due to drought, we also had the war in Ukraine. Whilst grain and oilseeds have been flowing from the country, it has been at reduced levels. So supply has been constrained.

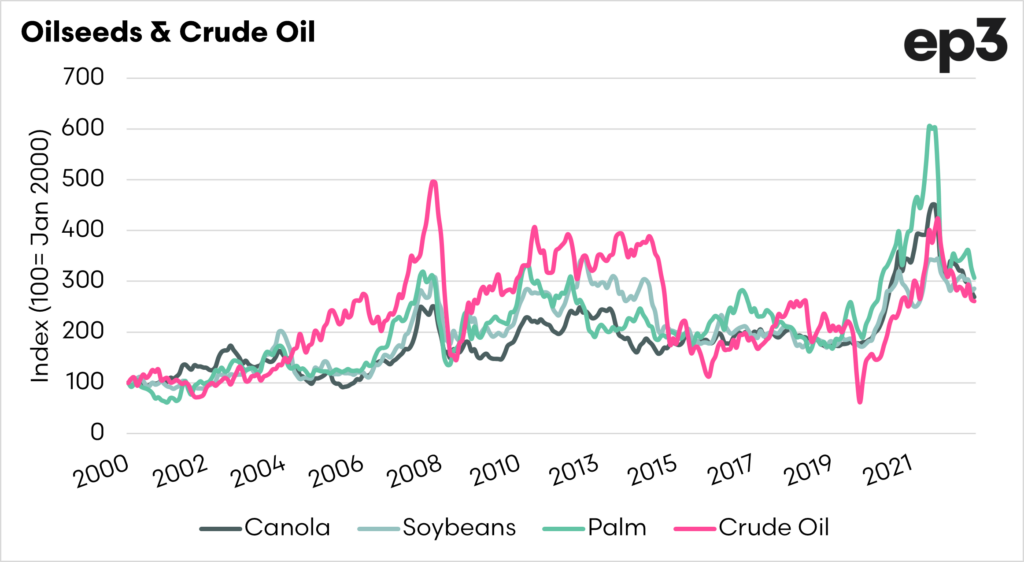

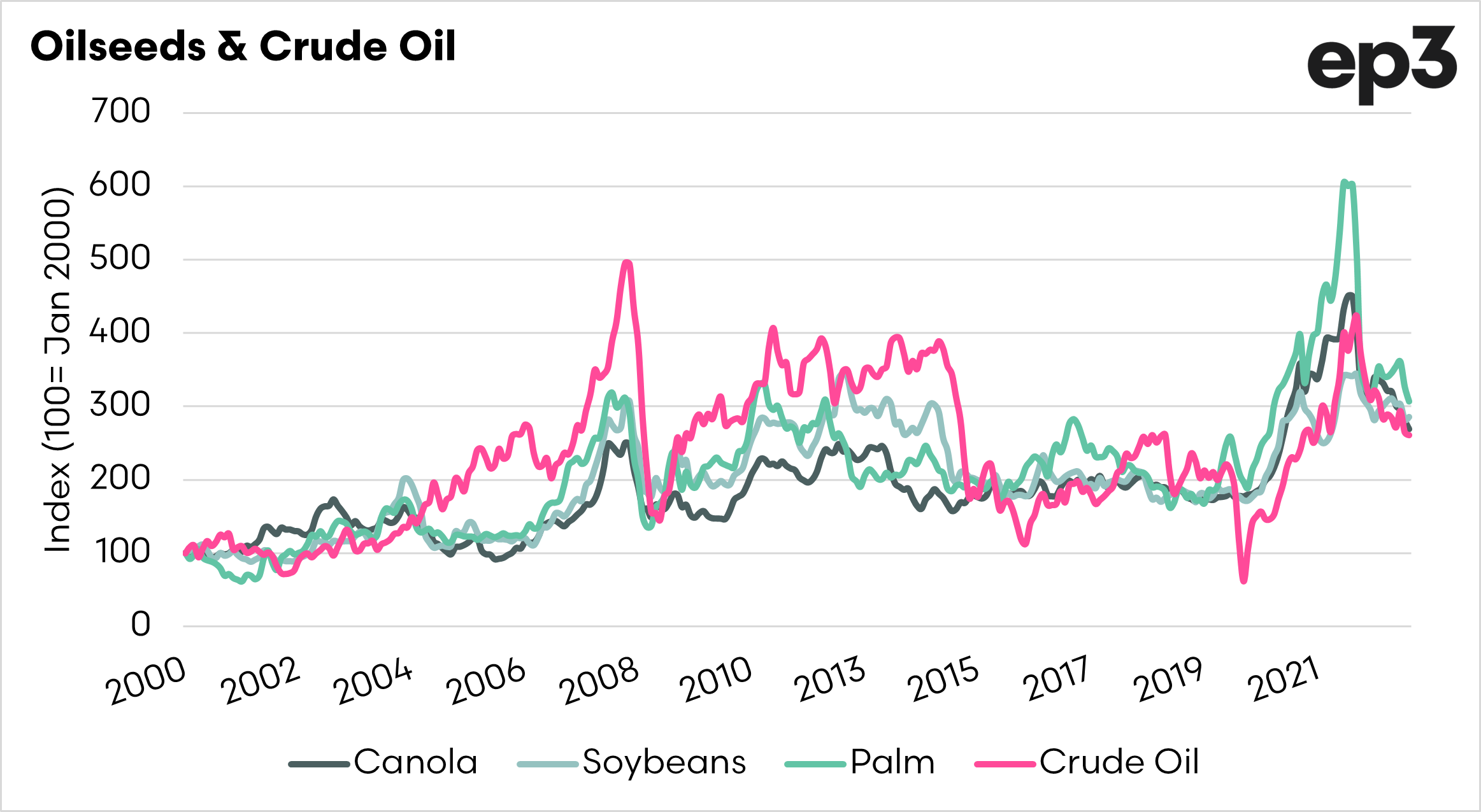

It is important to note that canola does not operate on its own. There is a high degree of substitutability between the various oilseeds (soybeans, palm etc).

There is also a close relationship between the oilseeds and crude oil. The issues around the Canadian canola crop were also at a time of high energy pricing. So the whole energy/oilseed complex was high. This provided Australian farmers an opportunity to participate in an environment with high prices and high production. Although as noted in many of our analysis pieced in recent years, our basis to matif and ice futures was low.

High prices are the cure for high prices.

If anyone takes heed of anything that we write on EP3 – ‘THIS IS THE NEW NORM’. If anyone says this to you, walk away from them. Commodity markets cycle up and down.

While not near the recent highs, prices for canola are still priced at historically high levels. This period (June-August) is volatile; if opportunities arise, they should be considered.