NZ Sheep Drop Australia’s Opportunity

Market Morsel

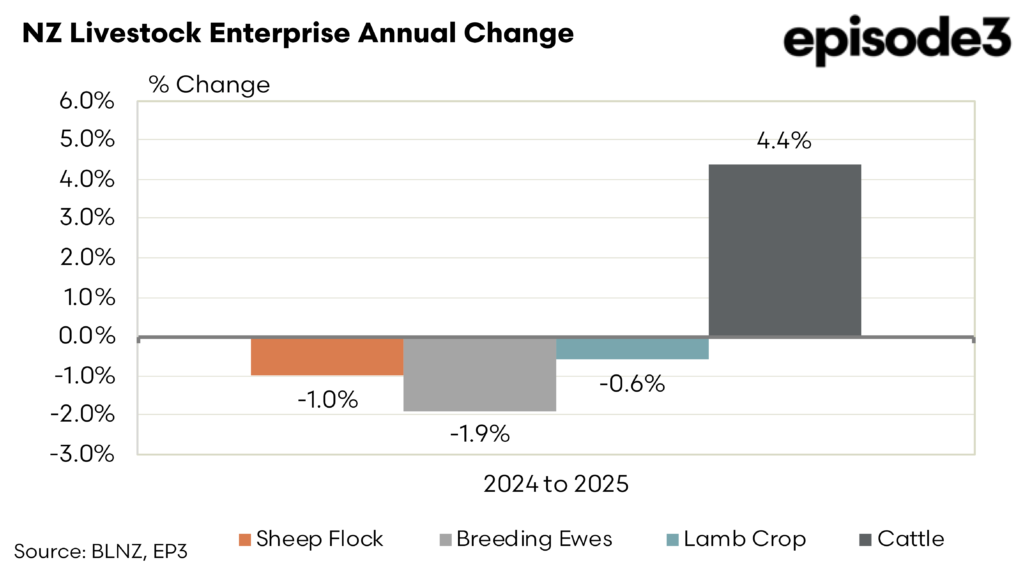

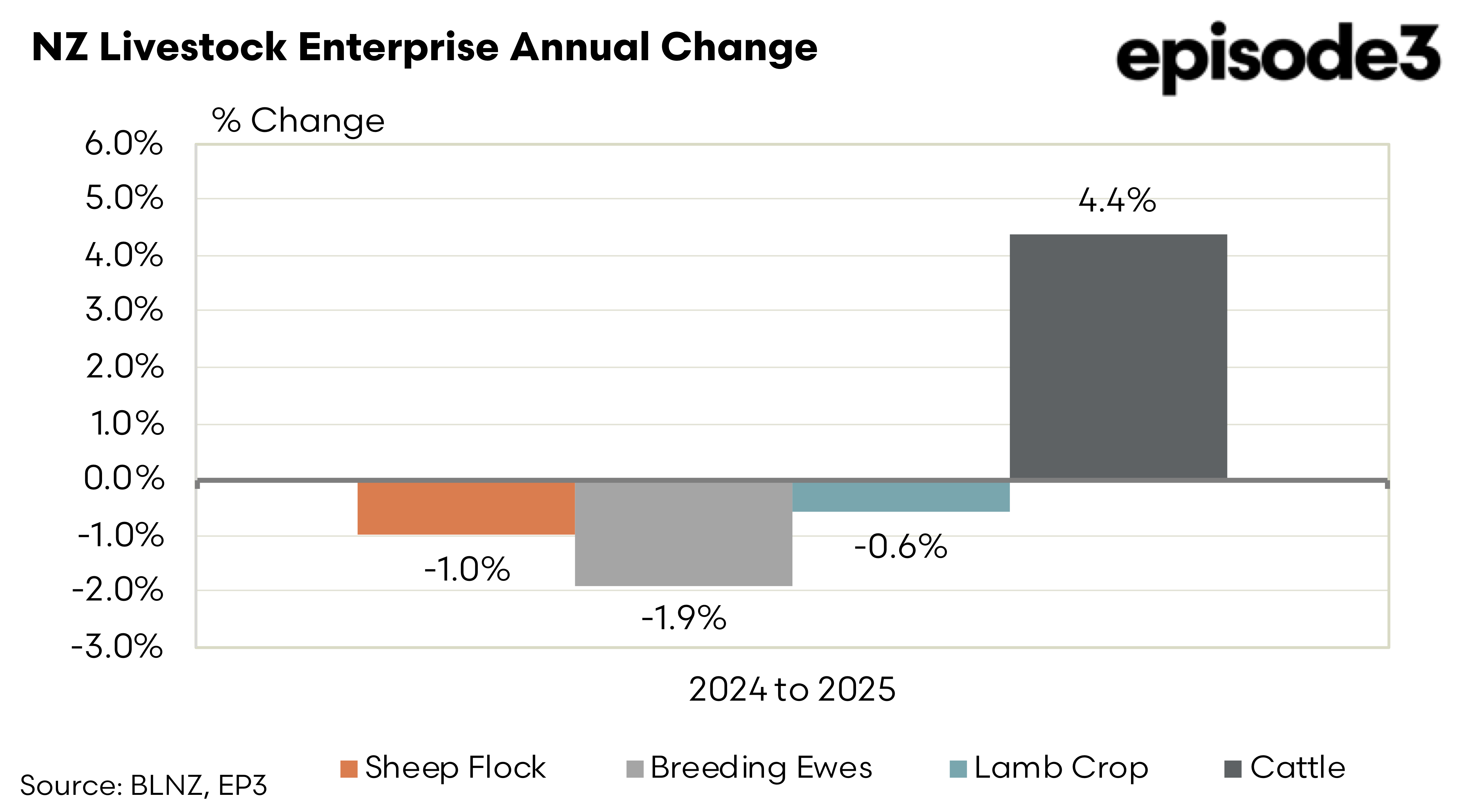

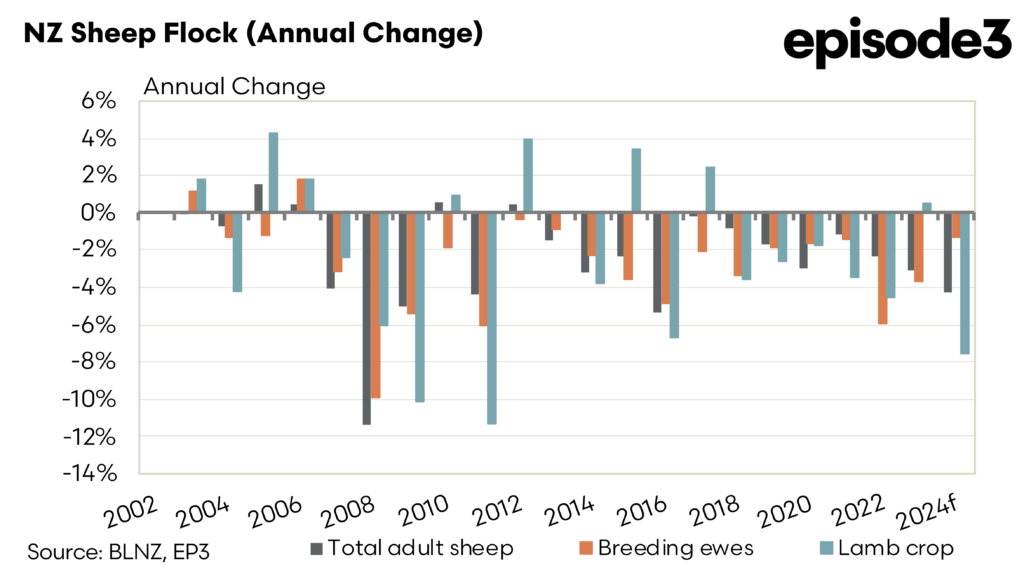

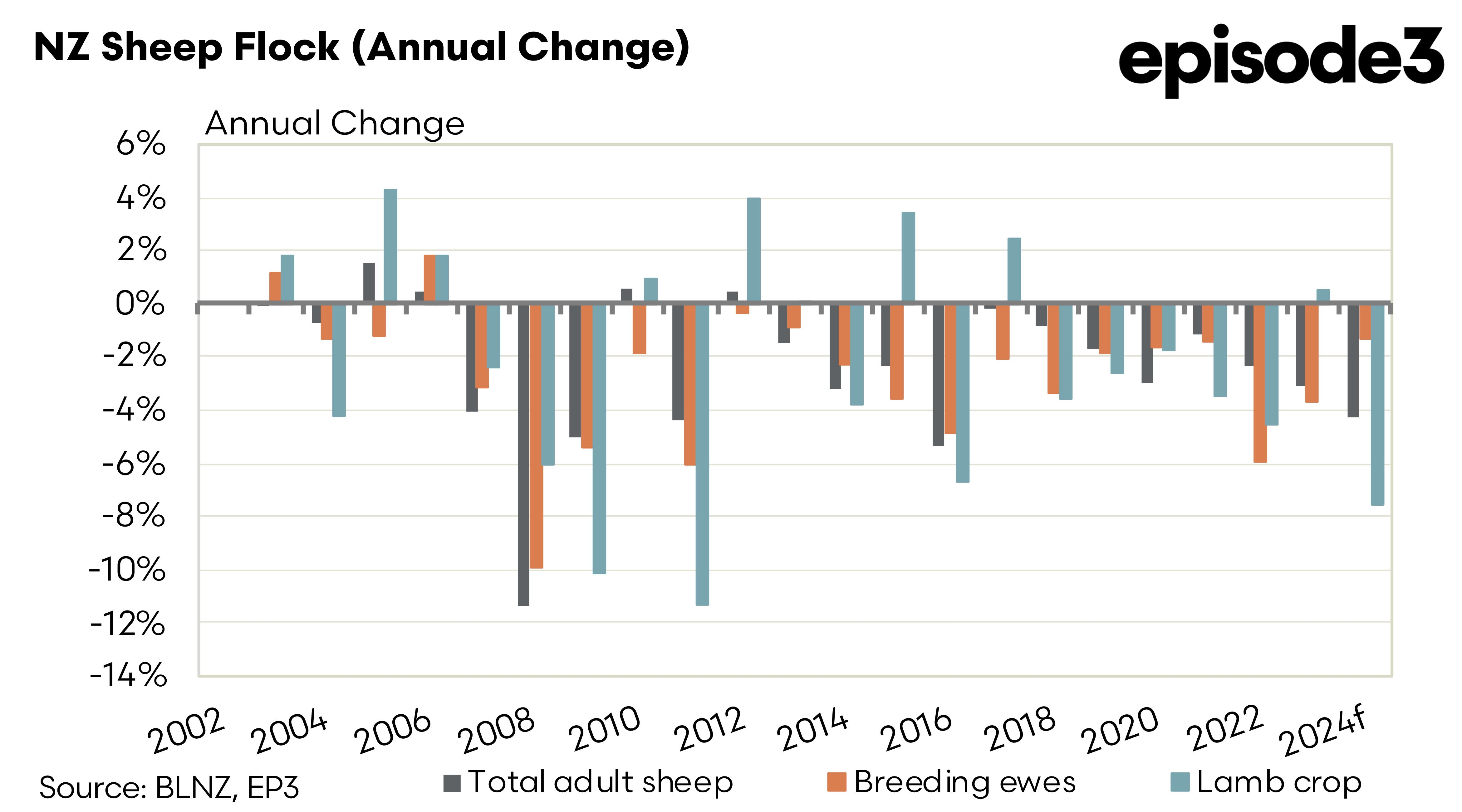

New Zealand’s sheep industry has continued its gradual contraction over the past year, with implications that extend well beyond domestic farming. Between June 2024 and June 2025, the national flock declined by 1.0% to 23.36 million head, a modest reduction compared to recent years but nonetheless part of a long-term downward trend that has seen sheep numbers fall by 45% since 2000.

More telling is the 1.9% fall in breeding ewes to 14.28 million, a metric that signals the sector’s future production capacity. While the total decline in numbers was softened by an increase in trading hoggets, the lower breeding base will inevitably constrain lamb output in coming seasons. The 2025 lamb crop is forecast at 19.29 million head, down 0.6% from last year, following a much larger fall the year before.

Several factors are driving the shift away from sheep. Land-use change, particularly the conversion of grazing land to forestry for carbon farming, remains a major structural pressure. Since 2017, more than 290,000 hectares of grassland have been afforested, accounting for over three-quarters of the total reduction in sheep and beef stock units. Economic incentives have also played a role, with consistently strong beef cattle prices prompting some farmers to rebalance their operations in favour of cattle, which typically require less labour and have faced fewer profitability swings in recent years. In 2024–25, beef cattle numbers rose by 4.4%, continuing a gradual reweighting within New Zealand’s mixed livestock systems.

Seasonal conditions have contributed to regional variation in performance. Areas such as the East Coast and Marlborough–Canterbury recorded increases in trading hogget numbers and, in some cases, overall flock growth as favourable feed conditions allowed farmers to rebuild after recent droughts and storms. In contrast, parts of the North Island saw sharper declines due to dry conditions and land-use change. These localised gains, however, have not offset the broader national trend of reduced breeding ewe numbers, which is the fundamental constraint on long-term supply.

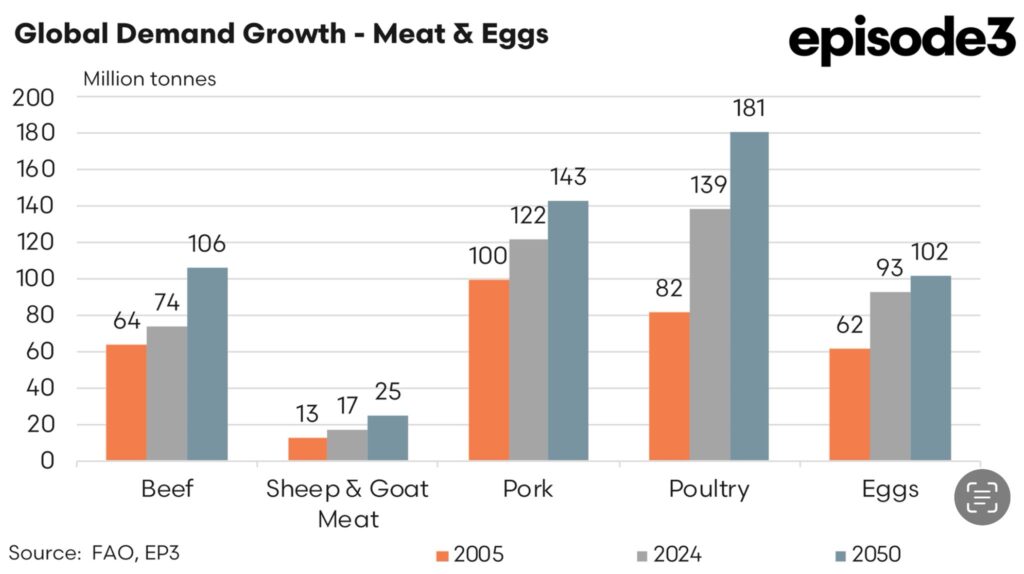

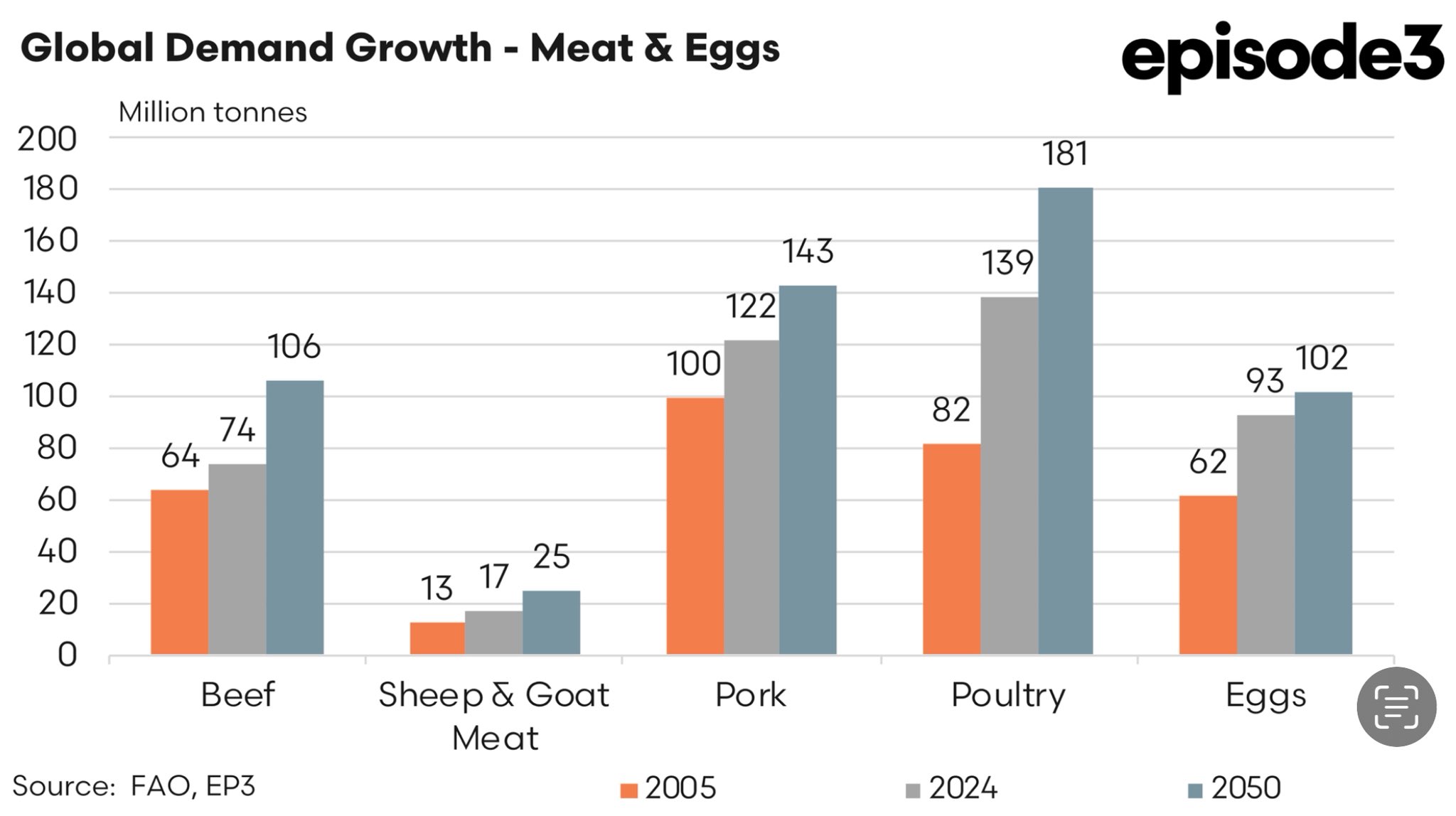

The contraction in New Zealand’s sheep sector comes at a time when global demand for sheep meat is expected to expand significantly. Historical and projected consumption trends show that combined demand for sheep and goat meat rose from 13 million tonnes in 2005 to 17 million tonnes in 2024, and is forecast to reach 25 million tonnes by 2050. This growth is being driven by rising incomes, urbanisation, and shifting dietary preferences in parts of Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Importantly, Australia and New Zealand together account for nearly 80% of global sheep meat exports, making them the pivotal suppliers to international markets.

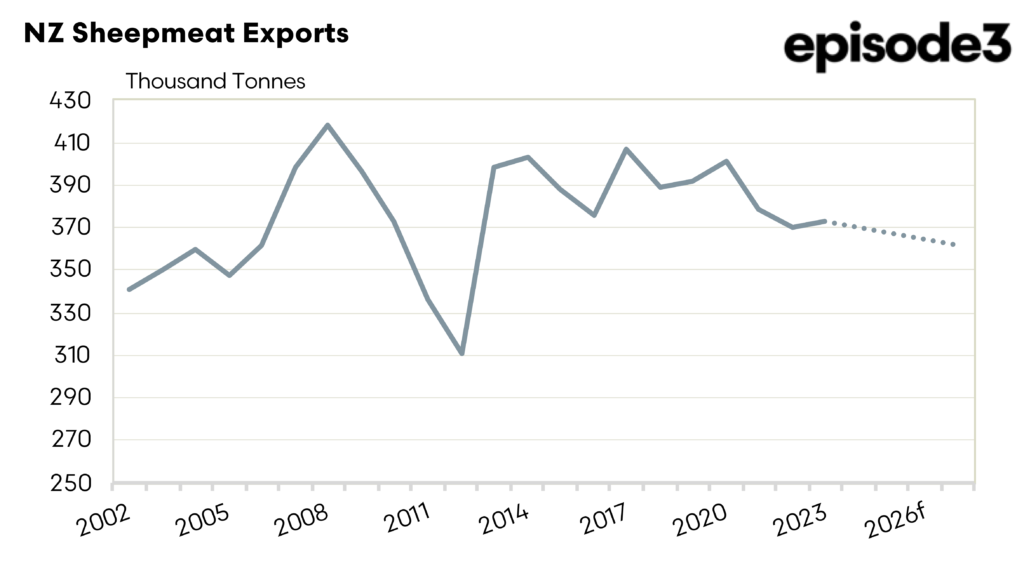

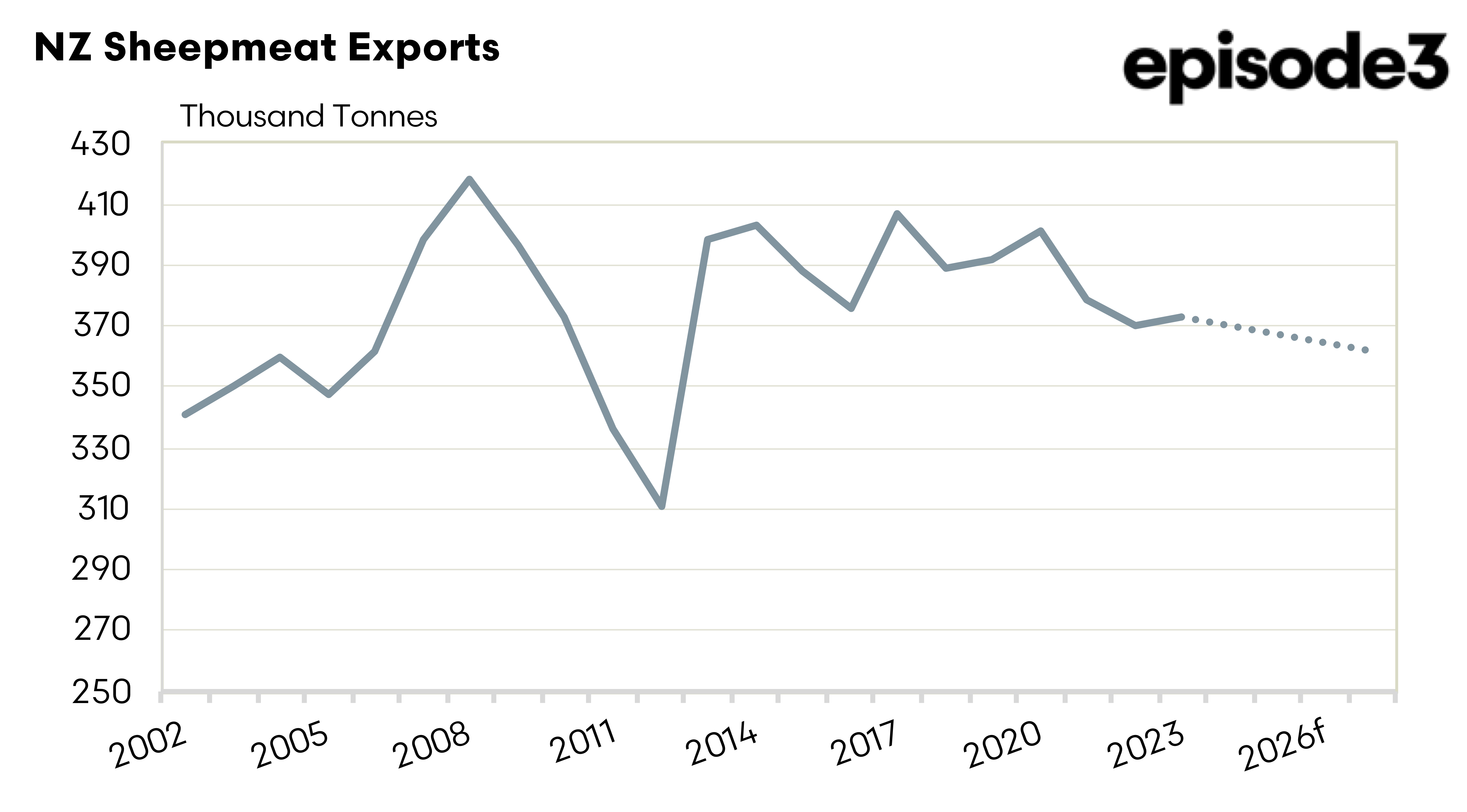

With New Zealand steadily reducing its sheep industry exposure, the balance of supply capacity between the two major exporters is shifting. If New Zealand’s breeding ewe numbers continue to decline, it will reduce its ability to meet rising global demand and maintain its current export share. This opens a strategic opportunity for Australia. As New Zealand’s exportable surplus tightens, Australia is well-positioned to expand production, consolidate market share, and strengthen relationships with key importers, provided it can navigate its own production challenges such as climate variability, land-use pressures, and biosecurity risks.

For Australian producers, the New Zealand trend underscores the importance of long-term planning and investment in the sheep meat sector. Expanding flock numbers, improving productivity through genetics and pasture management, and ensuring processing capacity aligns with potential increases in supply could all help Australia capture the opportunities presented by this structural shift. Market intelligence will be critical, as competition from other proteins—particularly poultry, which is forecast to see the largest growth in global meat demand—will remain strong. Nonetheless, sheep meat occupies a distinct and valuable niche in many high-value markets, meaning that supply shortfalls from one major exporter can translate into direct gains for the other.

In summary, while New Zealand’s 2024–25 sheep flock reduction is modest compared to some past years, it represents another step in a long-term contraction that is structurally reshaping global sheep meat trade dynamics. Given that the country’s breeding ewe base continues to shrink, its future exportable surplus is likely to diminish, creating potential for Australia to further cement its position as the dominant global supplier. For policymakers, processors, and producers alike, the challenge will be to convert this potential into sustained market advantage in the decades to come.