Wait and see in 2023

As 2022 draws to a close we take a look at what to watch out for next year in the Australian livestock sector. Picking out the top five things to keep an eye on we will start with the likely transition from the current wet season to the next dry spell beginning.

End of La Nina & looming El Nino

We are set to have three years in a row of wetter than normal weather, which has allowed the herd and flock rebuild to gather some good momentum. It is the impact of La Nina that has directed more moisture across the continent.

Analysis of the historic La Nina cycles since 1900 shows that there have only been three triple year La Nina events; 1954-1957, 1973-1976 & 1998-2001. So the current wet cycle is likely to finish into 2023, as there has never been an incidence of four La Nina years in a row.

In May 2022 we published a piece looking at the average number of years seen between wet to dry seasons across the nation and over the last 120 years the average gap came in at around 2 years, irrespective of the Australian state examined.

This suggests that by the middle of the decade we are likely to see parts of the country experiencing drier than normal conditions. The big question will be where this occurs, how severe the drought will be and for how long it will last?

By 2024 Meat & Livestock Australia (MLA) forecast the cattle herd to be at 28.9 million head and the sheep flock to be at 78.7 million head. Higher livestock supply will mean increased annual slaughter rates and red meat production. It will also mean that there will be plenty more sheep and cattle to turnoff should the season become more adverse, so a move back into herd and flock liquidation may be seen in parts of the country into the second half of the decade. This brings us to our second item to keep an eye on in 2023 – how red meat processors will cope with increased slaughter volumes given the lack of process workers and specialist boners/slaughterers.

Processor workforce bottleneck

Access to labour has been an ongoing battle across the agricultural supply chain from limited backpacker numbers for harvest work, difficulty finding and retaining farm hands to delays in access to shearing teams. Beyond the farm gate, the red meat processing sector has been particularly hard hit with processing capacity hamstrung by limited access to skilled and unskilled processing workers.

MLA slaughter projections for 2024 have annual cattle slaughter pegged at 7.8 million head and sheep/lamb slaughter at 30.2 million head, which will be the highest either slaughter volumes have been since 2019. This represents 20% more cattle being processed and nearly 10% more sheep and lamb than what was achieved in 2022.

During 2022 abattoirs reported capacity constraints due to labour shortages were impacting throughput levels. During the 2022 winter when Covid was hampering the abattoir workforce particularly harshly there were reported of processing capacity dropping toward 60%. Presently abattoirs are reporting capacity between 70-80% of normal flows is common, but the main hurdle to increasing processor output is access to labour, particularly for abattoir process workers.

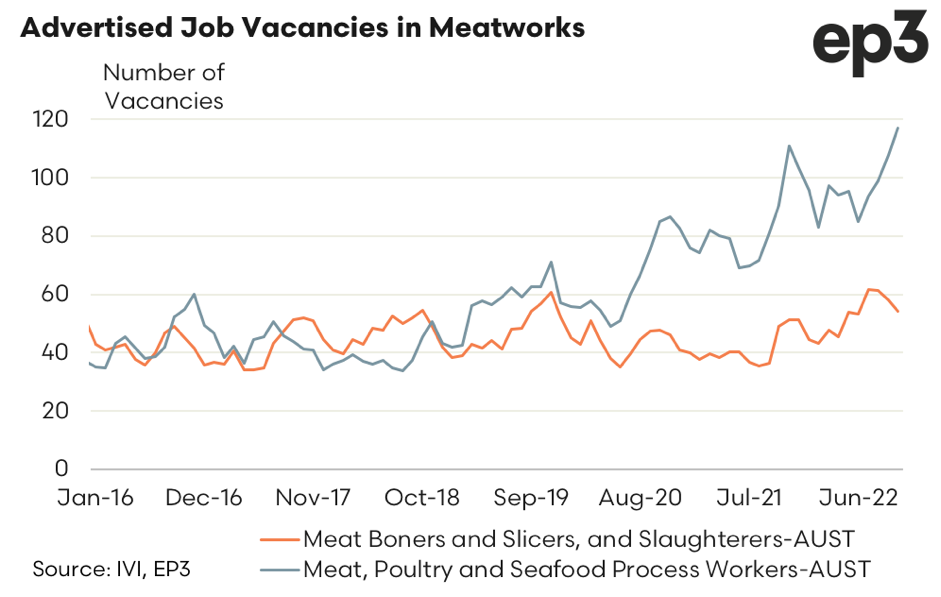

An analysis piece in early December released by EP3 highlighted the steady growth in job advertisements for meat process workers since the beginning of 2020 across Australia. In August 2018 there were 34 job ads for meat process workers nationally. However, October 2022 saw the level of job ads lift to the highest seen since the start of 2016 at 117 positions being advertised nationally. In percentage terms the current number of job ads for meat process workers is 244% higher than the levels seen back in August 2018.

A surge of livestock hitting saleyards & meat works in the middle of the season as concerns over the possible incursion of foot & mouth disease saw livestock prices come under significant pressure, albeit temporarily. Part of the price pressure was linked to the inability for processors to cope with the increased volumes due to labour constraints.

As an industry we need to ensure sufficient capacity exists in the red meat processing sector in the coming years to ensure we don’t get tripped up by supply chain bottlenecks as throughput volumes increase in line with herd and flock numbers.

US recession & China Covid woes

Higher herd and flock levels will mean increased red meat production available for export. However, there are a few dark clouds on the horizon that could act as a reasonable headwind on beef and sheep meat export demand and flow through to weaker livestock prices into 2023.

One of the most reliable indicators of impending economic recession in the USA over the last four decades has been the yield curve between 10 year and 2 year US bonds. More specifically, an inversion in the yield curve between these two financial instruments has preceded a recession in the US for five of the last six recessions since the 1980s.

The current strength of the yield curve inversion in the USA is the strongest it has been since the mid 1980s suggesting that a recessionary phase is likely to hit the US economy into 2023. A faltering US economy has implications for the global economy and can impact upon key agricultural commodities that are susceptible to economic growth levels and consumer confidence, such as wool and sheep meat.

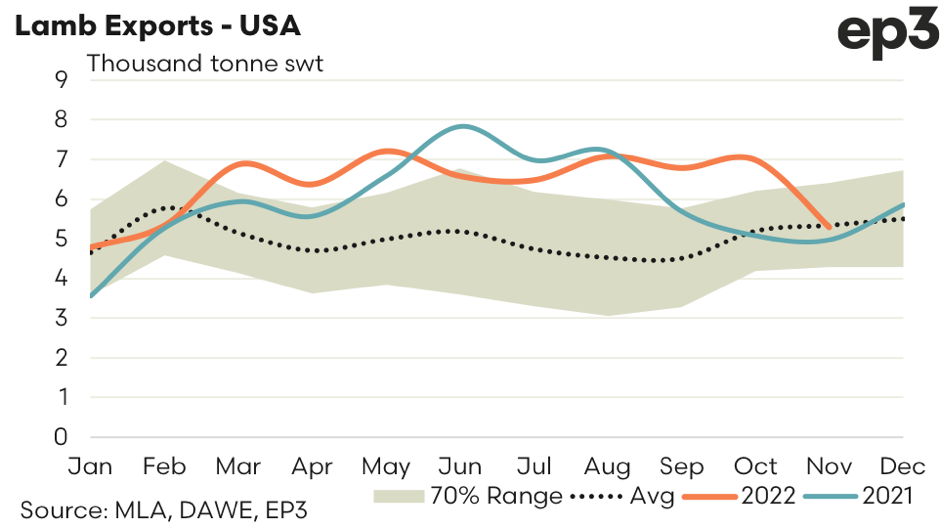

During 2022 and 2021 Australian lamb export volumes to the USA surged with average monthly volumes running 25%-30% above the five-year trend throughout much of the season. In the USA lamb is often consumed in the food service sector rather than at home.

Recessions are not good for the restaurant trade and consumers needing to save their pennies aren’t usually keen to eat out often or spend up big at a fancy restaurant so the prospect of a US economic slowdown into 2023 may take some of the momentum out of the US lamb export market into the new year.

Another economy that is crucial to maintaining global economic growth levels is China. Since the outbreak of Covid the Chinese authorities have been pursuing a zero Covid policy, with harsh lock downs implemented upon cities with disease outbreaks.

These series of lockdowns have been hampering the Chinese economy, holding back Chinese consumer confidence and spending. Over the first three quarters of 2022 the Chinese economy grew by just 3% compared to the 5.5% official target.

While a 3% growth rate doesn’t sound too bad, for a country like China that averages annual growth levels between 7%-12%, it is a dismal performance. Chinese demand for Australian wool exports is significant, taking around 80% of the clip and the Chinese consumer accounts for nearly 40% of our mutton export volumes. A Chinese economy under pressure into 2023 could pose some headwinds for a wool and mutton price recovery into the new year.

Spread of Lumpy Skin Disease

The spread of disease in countries to our north causing impacts to the Australian agricultural sector isn’t just limited to Covid-19. In the middle of 2022 the spectre of a Foot & Mouth Disease (FMD) incursion into Australia saw cattle and sheep prices slump, albeit briefly.

Additionally, African Swine Fever (ASF) continues to hamper a number of countries in south-east Asia and poses on ongoing threat of being imported into Australia in infected pork product being carried in illegally by tourists and returning travellers.

One positive to take from the risk of FMD or ASF is that attempts can be made at the border to control the chance of both of these diseases getting into the country. However, this is not the case with Lumpy Skin Disease (LSD) which is currently spreading across Indonesia towards Australia in a relatively uncontrolled manner, as it is predominantly spread by insect vectors.

The closer LSD gets to Australia the chances of an incursion of the disease blowing in on a tropical storm event increases. Indeed, an assessment of the risk of FMD getting into Australia, now that it is also in Indonesia, sits at nearly a 12% chance over the next five years compared to a 28% chance for a LSD incursion.

An outbreak of LSD in Australia would have trade implications for live cattle exiting Australia along with our boxed beef and dairy export products. Australia is currently LSD free, so an incursion of the virus would require renegotiated trade access for multiple products across multiple destinations.

This export renegotiation could take many months or years to arrange, which would pose a significant threat and cost to sectors like the beef and dairy trade, where significant volumes of annual production are exported. In 2022 around two thirds of Australian beef product was exported and approximately one third of Australian milk production was exported.

Decline of the live sheep export trade

While disease poses a potential threat to key agricultural export markets like beef and dairy there has been a realised impact upon live sheep export markets, leading to an ongoing decline of the sector.

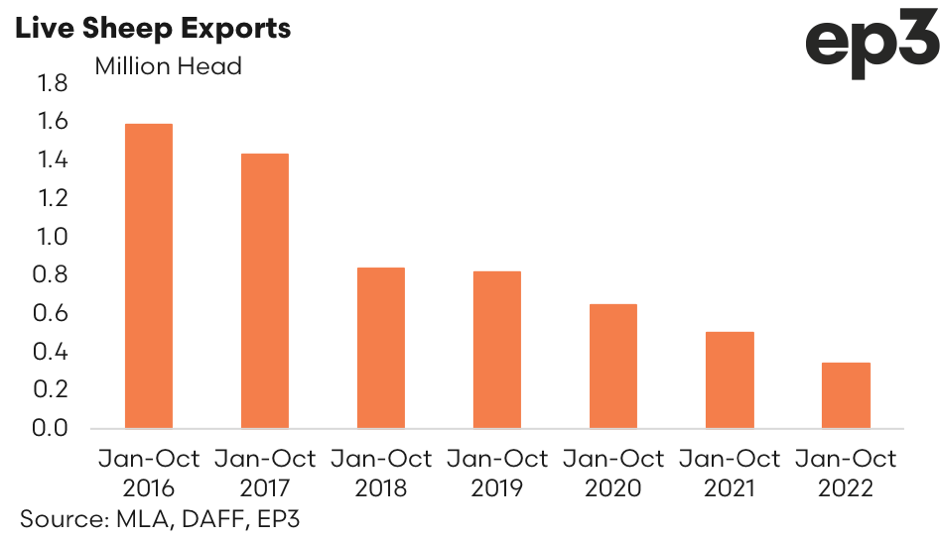

Analysis of the total live export flows from January to October 2022 shows that the sheep trade is underwhelming this season. Sheep export volumes are running 32% under the export levels recorded during this timeframe in 2021. January to October 2021 saw 500,318 head of sheep transported versus 339,090 so far this year. A look further back in time shows that the decline has been particularly evident since the introduction of the northern hemisphere summer moratorium in 2018. Annual live sheep export volumes are around one quarter of what they were five years ago.

It was just a decade ago that the live sheep export industry was both an east coast and west coast affair. In 2011 around 30% of the live sheep export volumes exited the country from ports outside of Western Australia. However, since 2018 the trade has been predominantly a WA led industry, in terms of port of exit with at least 98% of the annual live export turnoff of sheep leaving from the west.

During 2020 and 2021 there was an increased trade in live sheep from Western Australia to the eastern states with 1.9 million head of sheep and lamb making their way across the Nullarbor in 2020 and 0.7 million head in 2021, providing an alternative outlet for sheep turnoff instead of live export.

However, this year there has only been 0.3 million head of sheep transported east (as at November 2022) so that hasn’t really been a significant option for turnoff for the WA producer, compared to previous seasons.

That leaves the domestic meat works in WA to pick up most of the turnoff, with slaughter volumes representing over 80% of the sheep and lamb turnoff for WA so far in 2022. However, abattoirs across the country have been struggling under the lack of labour, capacity constraints, high operational overheads and very slim margins as outlined earlier in this piece. Meat works in WA have been no exception to the labour shortage issues facing the red meat processing sector.

If we are planning to exit the live sheep trade we need to ensure that abattoirs, particularly in WA, are well supported to step into fill the gap that will be left. Otherwise WA producers will bear the brunt of adverse saleyard price reactions, if there is a backlog of sheep and lamb to process next year as the flock numbers continue to climb and slaughter volumes lift.