Circle the wagons?

The Snapshot

- The Australia – India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement (ECTA) came into effect on 29th December 2022.

- Estimates from the United Nations have the population in India growing by more than 300 million people between 2030 to 2050, which will underpin increased consumption of agricultural commodities.

- Additionally, the increasing wealth of the average Indian has fuelled a rise in consumption of many agricultural products, including food.

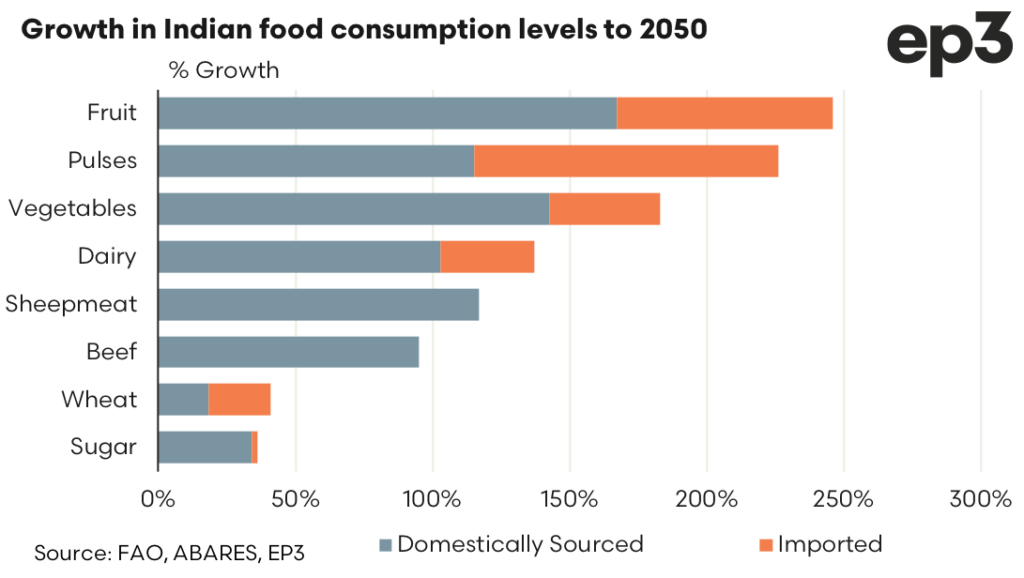

- It is projected that from 2009 to 2050 food consumption in India for fruit and pulses will climb by more than 200%. Meanwhile, the consumption of vegetables and dairy product will more than double.

- Around half of the growth in demand for pulses and wheat expected by 2050 in India will need to be satisfied by imported product.

The Detail

The Indians are coming…. to trade more, hopefully.

The Australia – India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement (ECTA) came into effect on 29th December 2022, which means that around 85% of the current Australian exportable items (by value) are now free of tariff. Over the next six years tariffs will reduce on the remaining Australian exports so that around 90% of items will get access to India on a tariff free basis.

This provides a huge opportunity to the Australian agricultural sector, particularly as the years progress, with the consumption levels of key Australian agricultural products forecast to boom in India as their population grows in both size and wealth.

Estimates from the United Nations have the population in India growing by more than 300 million people between 2030 to 2050 and it is not just the sheer weight of numbers adding to consumption levels in India. Over the past two decades the per capita inflation adjusted gross domestic product (GDP) in India has increased 6% per year, on average.

This increase in economic prosperity has taken the per capita wealth levels of the Indian population from around $750US to over $2,000US, which is nearly a tripling of real GDP per person.

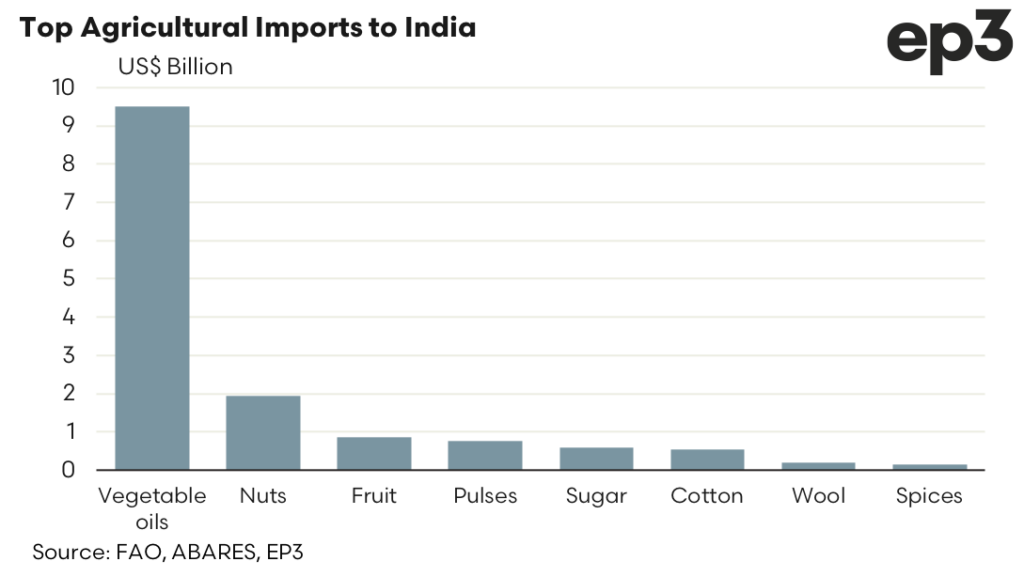

The increasing wealth of the average Indian has fuelled a rise in consumption of many agricultural products, including food. Over the last decade some of this leap in consumption has been accommodated by a surge in imported products. The value of fruit, nuts, cotton and dairy imports into India more than doubled and imports of barley lifted by 275%. Agricultural imports to India are dominated by vegetable oils and reflect the mainly vegetarian diet of much of the Indian population. But times are changing.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) projected that from 2009 to 2050 food consumption in India for fruit and pulses will climb by more than 200%. Meanwhile, the consumption of vegetables and dairy product will more than double. Sheep meat consumption (including goat) will lift by nearly 120% and, somewhat surprisingly given the large Hindu population in India, the consumption of beef & buffalo meat is anticipated to lift by 95%.

It is something that often goes unnoticed in India but there is still a sizeable Christian population in some provinces and, when their income levels allow it, are happy to eat beef. Indeed, the Christian population in India is estimated to be around 2.3% of the total population, so in a population of 1.4 billion Indians there is around 32 million Christians that are happy to eat beef.

Unfortunately, for the Australian beef producer India has a huge cow and buffalo herd, mainly used for dairy production. This means that despite the significant increase in beef consumption levels as India progress toward 2050 it is expected that all of this extra beef demand will be able to be satisfied by domestic production, so there will be little need to source additional beef product via imported channels.

India also have a significant sheep and goat herd, estimated at 75 million head and 150 million head, respectively. As of 29 December 2022 Australian sheep meat exporters will have access to India without the 30% tariff being applied. However, with a sizeable domestic market it may be difficult to penetrate and capture market share. Indeed, FAO forecasts suggest that all of the anticipated growth in Indian sheep meat consumption as we head towards 2050 will be satisfied from their domestic sources.

Although, I’m not convinced that the wealthy Indian consumer won’t want to sample the delights of top quality Aussie lamb and mutton exports and Meat & Livestock Australia, along with exporters, have done a great job over the last two decades promoting Aussie red meat to the world establishing a diverse market so I suspect there will be opportunities that present themselves.

Additionally, according to the FAO estimates, there are some good opportunities for the Australian horticulture farmer or broad-acre cropper to access the potential growth in demand from the Indian consumer. Around half of the growth in demand for pulses and wheat expected by 2050 in India will need to be satisfied by imported product. A third of the lift in fruit consumption will have to be met by imports and about a quarter of the rise in vegetable and dairy consumption in India will need to come from overseas sources.

Australian farmers will need to circle the wagons, as the Indians are coming. However, it won’t be a defensive position. It will be to set up a farmer’s market.