Always compare apples to apples when financing.

Summary & key takeouts

- Farm BNPL products avoid consumer rules, meaning no requirement to disclose APRs or comparison rates.

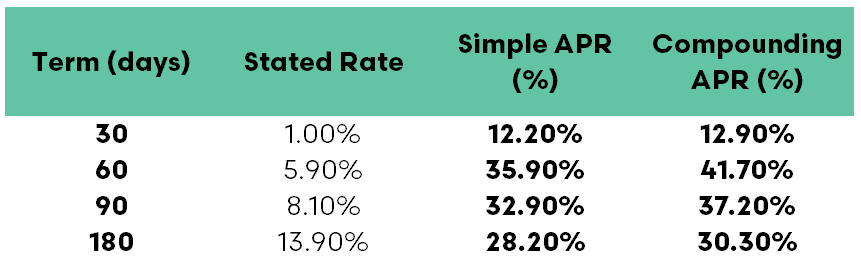

- Headline fees like 8.1% for 90 days actually annualise to more than 30%, far higher than typical farm overdrafts.

- BNPL dramatically increases downside risk, turning flat or slightly weaker markets into significant losses.

- Even the cheapest BNPL terms annualise above many bank rates, and late fees can push total costs toward credit-card levels.

Buy now, pay later (BNPL) schemes have swept across Australia, and they are now in the agricultural space. They allow access to easy finance with little documentation. They have changed how people purchase goods, especially the younger millennials and Gen Z. They are convenient with no traditional credit checks, but they are not without issues. Consumer regulators have repeatedly warned about late fees, missed payments, distorted budgeting and a tendency for users to treat BNPL as if it is cost-free money. As complaints mounted, the Federal Government stepped in to tighten the rules, forcing greater transparency and stronger safeguards for everyday Australian consumers

Now, however, BNPL has moved aggressively into agriculture, and it sits outside the consumer protections applied elsewhere. Farm-focused BNPL products are structured as business-purpose finance, meaning providers do not have to disclose an APR (annual percentage rate) or a comparison rate. This regulatory gap allows lenders to present their pricing as attractive-sounding short-term rates, even when the annualised cost is closer to credit card territory than to farm finance. At least with a credit card, you’ll get some frequent flyer points!

One provider charges 5.9% for 60 days or 8.1% for 90 days. These figures appear attractive, but once converted into annual terms, the picture is very different. A 90-day fee of 8.1% equates to over 30% interest. A 13.9% six-month fee is close to 30% annually. In contrast, most farm overdrafts fall between 6 and 11%. Without APR disclosure, farmers end up comparing a short-term fee to a full-year rate, making it easy to underestimate the actual cost.

The financial impact becomes clearer when applied to real decisions. A farmer who funds a $100,000 livestock purchase on 90-day terms pays $8,100 over just three months. When that 8.1% charge is converted to an annualised rate, it has an APR of roughly 32–37%, depending on whether you use simple or compounding APR. The APR is the only really fair way to compare lending rates, as it is closer to an apples-for-apples comparison, not a turnip-for-apples.

The farmer has to see a significant rise in the market to benefit. They always need to cover a significantly higher interest rate than the overdraft rate before they start making a profit.

Flat markets become costly, too. Buying lambs at $150 per head under a 90-day BNPL arrangement lifts the financed cost to $162.15, meaning the farmer loses $12.15 per head. If the market stays flat, a $3,645 loss on 300 head purely due to the financing fee. Under a standard overdraft at a conservative 7.5% per year, the cost for the same 90-day period would be roughly 1.9%, or just $2.85 per head, a far more negligible impact than the BNPL charge of $12.15.

The risk becomes catastrophic if the market doesn’t move in your favour. If lambs drop to $135 by the time they are sold, the return is now $27.15 below the financed cost per head. Across 300 lambs, that is an $8,145 loss, driven not only by the market decline but also by the extra leverage created by the BNPL facility. In both cases, the lesson is the same: buy now, pay later finance magnifies downside exposure. What looks like a small fee on paper becomes a significant loss generator when markets soften, and in volatile commodity markets, that risk is always present.

Some BNPL providers promote their model as a way of “sharing the upside” with farmers when market opportunities arise. In reality, the structure does the opposite. The lender earns a high, fixed return every time, while the farmer bears all the exposure to price movements. If the market rises, the producer may still profit, but if prices stall or fall, the farmer absorbs the full downside, plus financing costs. There is no actual sharing of outcomes. The lender’s return is guaranteed, and the risk sits squarely with the producer.

Compared with traditional finance, the gap is stark. Even the cheapest BNPL term, 1% for 30 days, annualises to roughly 12.2%, still higher than many overdraft rates. Add late-payment penalties of around 2.5% per month, equivalent to another 30% annually, and costs can escalate rapidly for anyone caught by delays in harvest, livestock sales or seasonal conditions.

None of this means short-term finance has no role in agriculture. It can bridge timing gaps or fund urgent purchases when conditions align. But convenience must never replace understanding. Before entering any BNPL agreement, farmers should insist on knowing the annualised equivalent rate, check how early (and late) repayment is treated, and understand rollover and penalty structures. An accurate comparison requires converting every short-term fee into an annual cost.

In a sector where every dollar of margin counts, understanding the real cost of finance is as important as understanding the market itself. BNPL may offer speed and simplicity, but those advantages mean little if the actual price is hidden behind short-term percentages that disguise annualised costs. Farmers should view these products with the same scrutiny they apply to livestock prices, grain markets or input contracts.

The safest approach is straightforward: slow down long enough to run the numbers, ask for the annual rate and make decisions based on full information rather than marketing gloss. As BNPL is sold to farmers as a convenient form of debt, it is time for the industry to demand the same transparency afforded to everyday consumers, including clear APR disclosures. In a volatile sector, clarity is not a luxury; it is protection.