The ticking timebomb inside the live export trade.

Australia’s live cattle export industry depends on a small fleet of livestock carriers that shoulder an enormous share of the nation’s northern marketing capacity. Yet a close look at those vessels shows a structural problem that can no longer be ignored: the fleet is old, in some cases extremely old, and without new investment, the trade will not remain viable.

To examine the live export fleet, we have analysed vessels utilised in recent years. Several of the ships carrying Australian cattle are far past the age at which most commercial vessels are retired. The Al Messilah, built in 1980, is nearing 45 years of service. The Maysora, built in 1989, is 36 years old. In almost any other maritime sector, ships of this age would have been dismantled long ago.

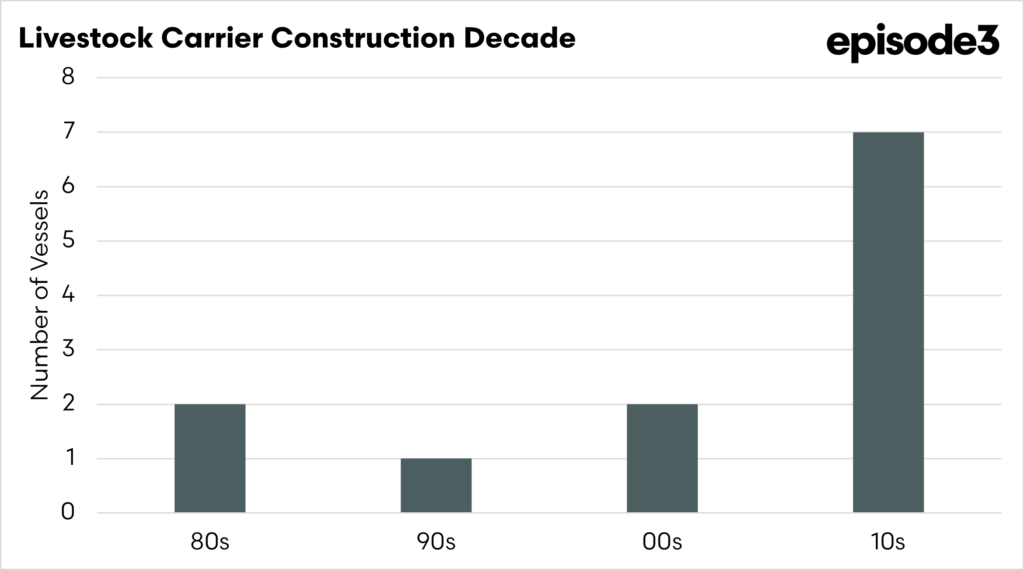

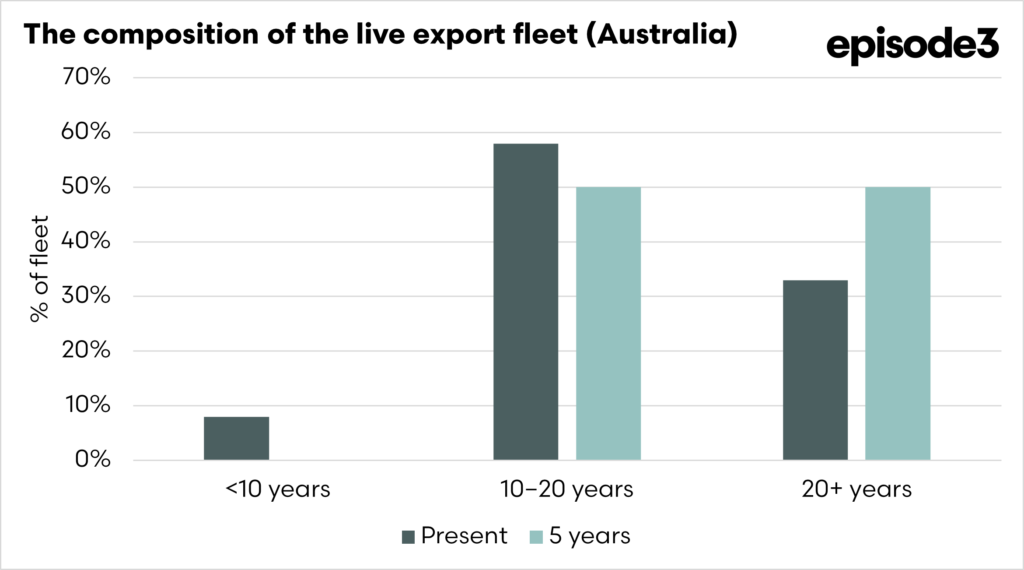

Even the “younger” end of the fleet reveals ageing infrastructure. The Brahman Express (2002) is now more than two decades old. The Ocean Swagman (2009) and Bahijah (2010) are approaching midlife, at which maintenance demands accelerate. Only a small number of vessels, such as the Al Kuwait (2016), the Girolando Express (2014) and the 2017 Friesian Express, represent modern tonnage built to contemporary engineering standards.

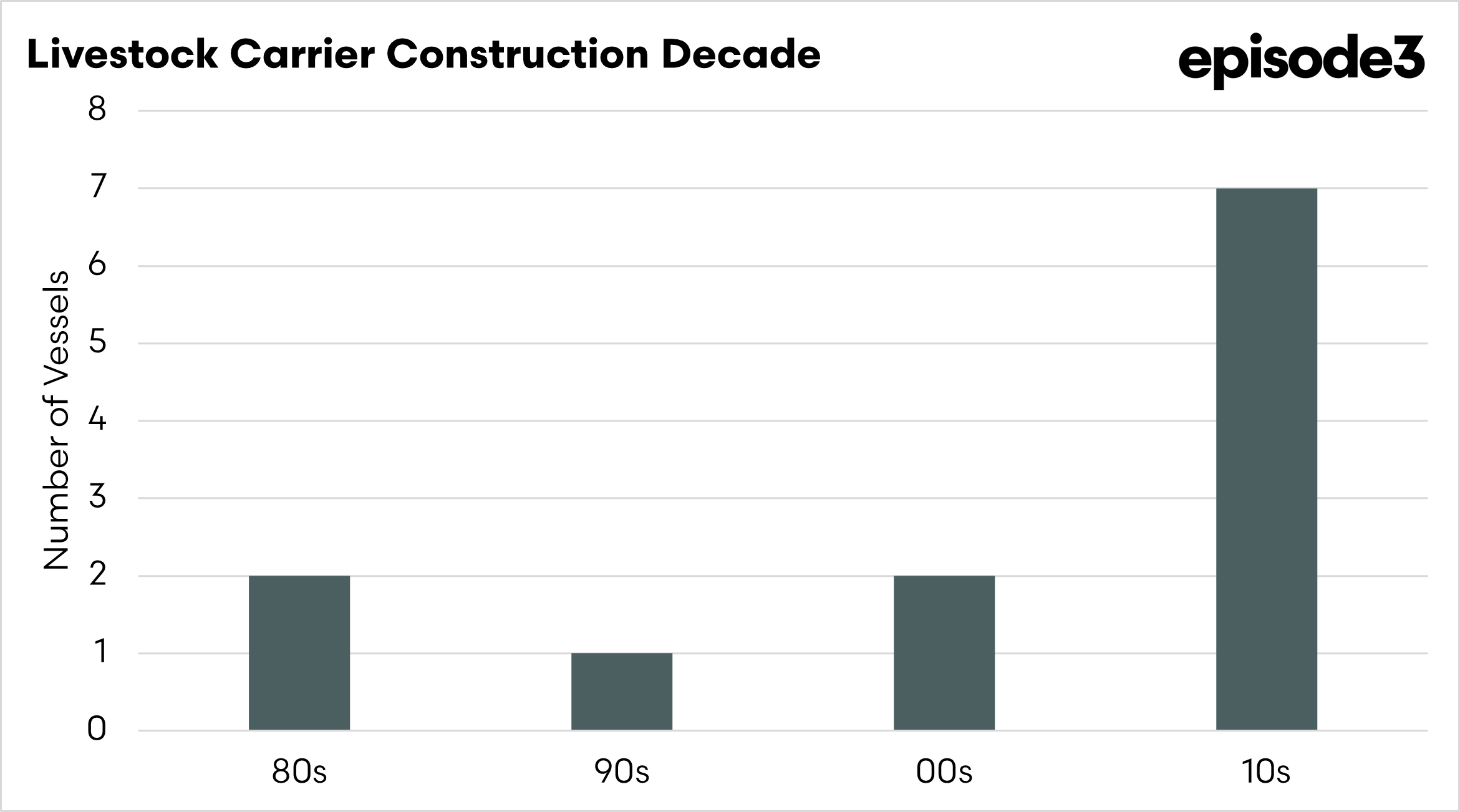

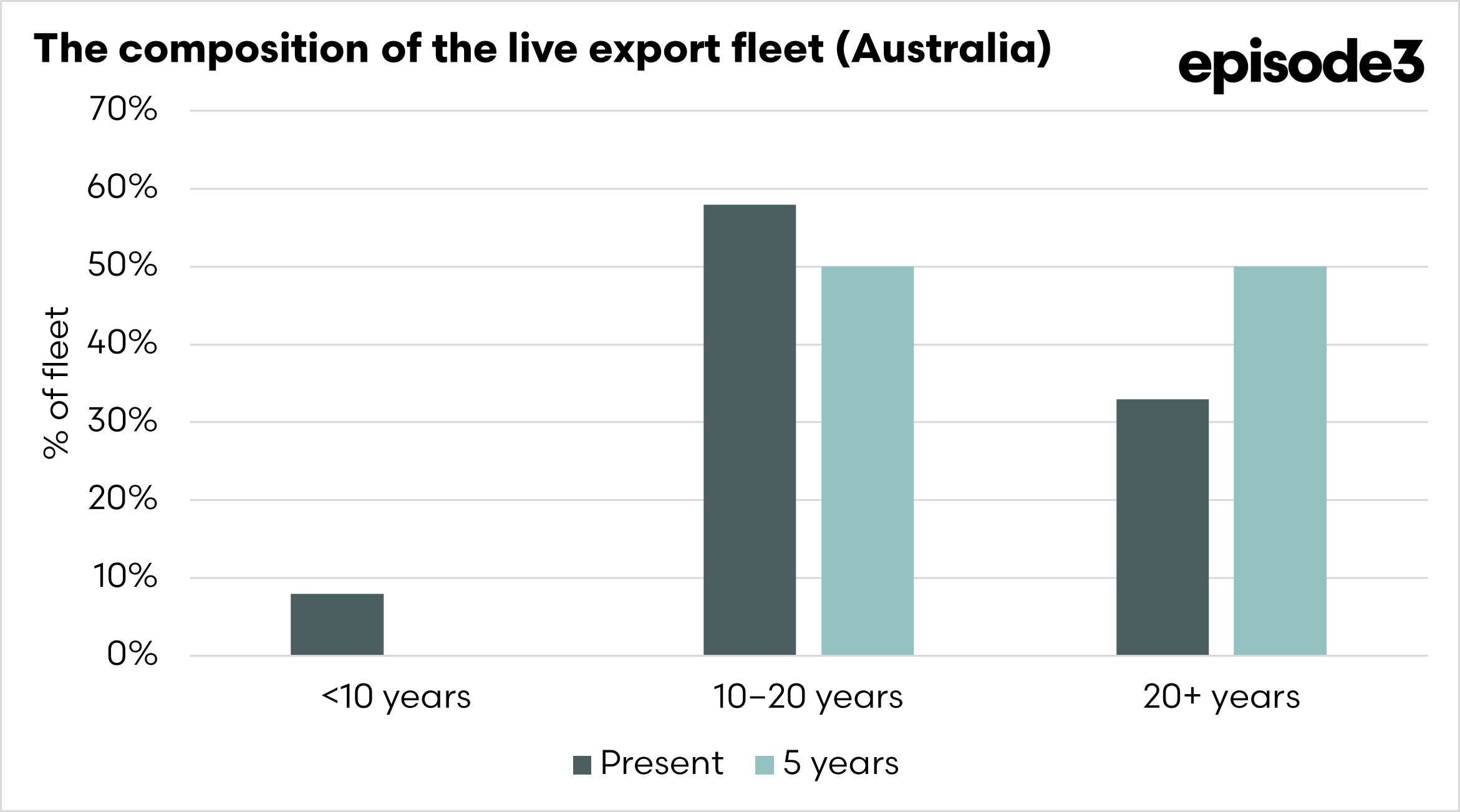

When all vessels are considered together, the age distribution is confronting. Based on the current age profile of Australia’s livestock vessels, the outlook over the next five years is deeply concerning. In a few short years, every ship in the fleet will be more than ten years old, and half will be over twenty years old. Unless more ships are launched, the industry faces a looming threat.

Age is a significant factor because livestock carriers are mechanically complex and demanding vessels at sea. This includes ventilation systems, desalination, waste handling, environmental controls and feeding. As vessels age, these systems require more maintenance and are more prone to failure. A breakdown in a 20-year-old ship is a maintenance challenge; a breakdown in a 40-year-old ship can be a crisis.

When shipping capacity tightens, the effects are immediately felt by producers: reduced demand, weaker price competition, and fewer marketing alternatives. The physical age of the fleet directly influences the economic resilience of northern cattle markets.

Yet despite the clear need for renewal, investment in new vessels is slow. The main reason is that building a modern livestock carrier requires long-term confidence that the trade will continue, that volumes will remain strong, and that regulatory frameworks will be stable. While industry organisations like ALEC rightly draw attention to political risks, repeated public messaging emphasising threat and uncertainty has the unintended effect of discouraging investment. Shipping financiers and owners hesitate to commit hundreds of millions of dollars if the industry itself appears unsure of its future.

This does not mean industry bodies should remain silent about challenges. But it does mean that a balanced narrative is crucial. Highlighting risks without also articulating a clear long-term vision for the trade makes it harder to attract the very capital needed to renew the fleet.

What is certain is that the current fleet cannot carry the industry into the next decade without significant renewal. Vessels such as the Al Messilah, Maysora, and Ocean Ute are operating on borrowed time. Even mid-aged vessels will face escalating maintenance, survey, and insurance requirements as they enter their third decade. Without a deliberate strategy, the Australian live export industry risks having insufficient vessels to meet demand, not because markets have disappeared, but because the ships have.

Investment in a new generation of livestock carriers is therefore not simply desirable; it is essential. Modern ships offer improved ventilation, stronger corrosion protection, more reliable engineering and better welfare outcomes. They pass regulatory inspections more easily, give importing nations confidence, and reduce the risk of capacity shocks. Most importantly, they ensure that live export remains a competitive outlet, supporting producer prices and offering genuine alternatives to domestic processors.

The age of the fleet is no longer a technical detail buried in shipping registries. It is a defining factor in the long-term viability of Australia’s live cattle trade. The fleet is ageing, and as it does, maintaining and achieving Australian compliance will become more costly.

The industry faces a choice: pursue long-term plans for new vessels or risk erosion under ageing infrastructure.

If producers want live export to remain strong, efficient, and competitive, the message is clear: new ships must be built, and the industry must foster the conditions that enable that investment. Fleet age is the challenge.

If nothing is done, the government won’t have to phase out live cattle exports; it will phase itself out.