Full steam ahead (literally) for containers.

The Snapshot

- Container rates have risen since the lull caused by the early stages of the COVID outbreak.

- The majority of the rise is in the China routes

- Container levels have yet to reach the height of the pre-GFC boom.

- Container ships have increased their speed due to the higher revenues.

- The rise is in part due to logistical positioning, with most demand originating from China due to their recovery.

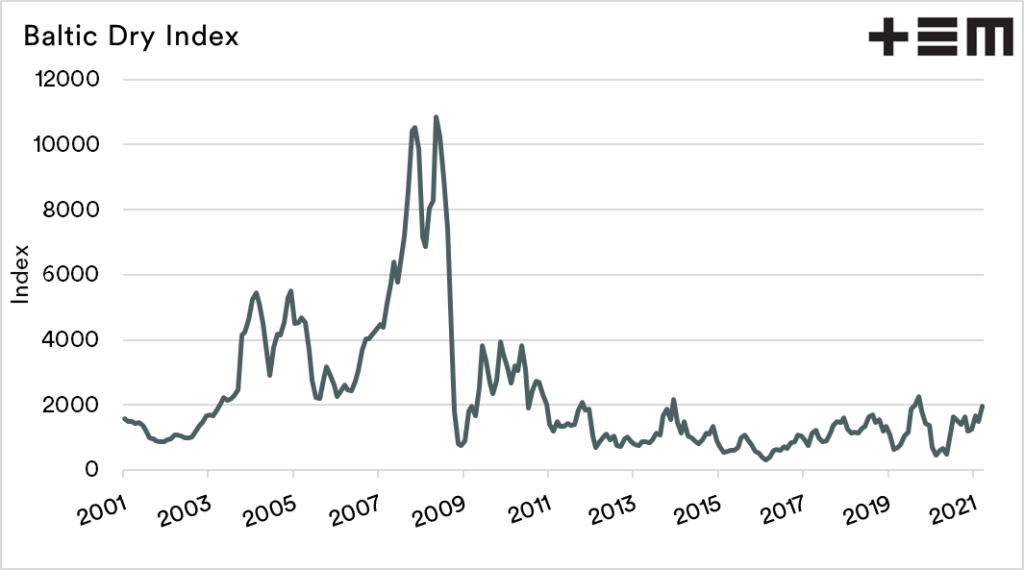

At EP3, we often report on the Baltic Dry Index (BDI) and its importance to shipping bulk commodities such as grain. However, bulk is not the only way to move our goods.

Andrew Woods mentioned this in his weekly wool update (see here), and one of our old colleagues in the wool industry asked us to shine a light on it.

Numerous products are moved by containers, mainly finished products from fidget spinners to fridges. However, agricultural commodities are also moved in boxes such as wool and reasonable quantities of grains.

The last update on the BDI showed that levels were currently following seasonal trends and had risen after falling during the early stages of the COVID outbreak (see here).

The container market, however, has been charting its own course. The container market followed a similar pattern to lots of different commodities, with a collapse of levels in the first and second quarter of 2020. However, since then, the levels have gone into the stratosphere.

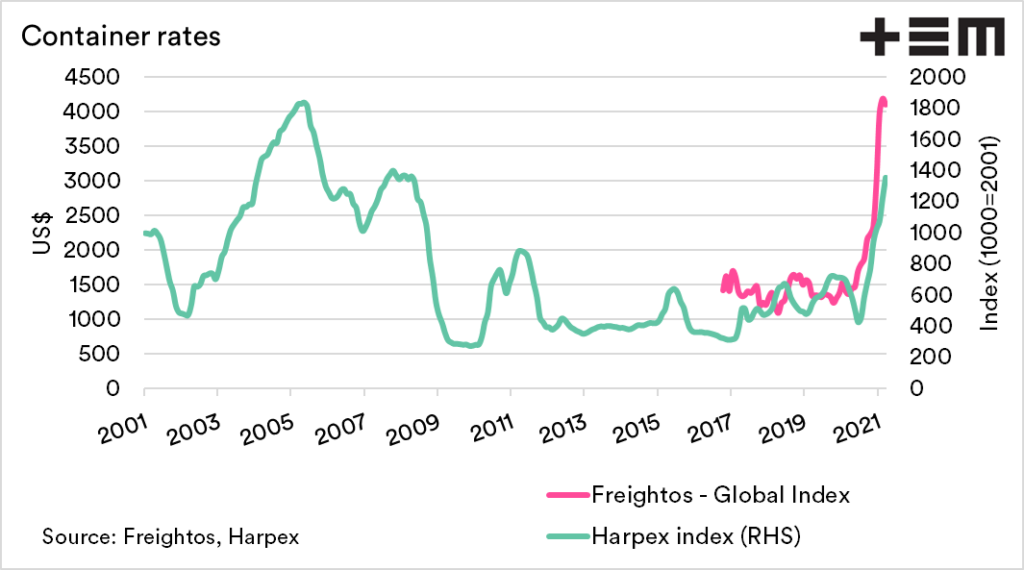

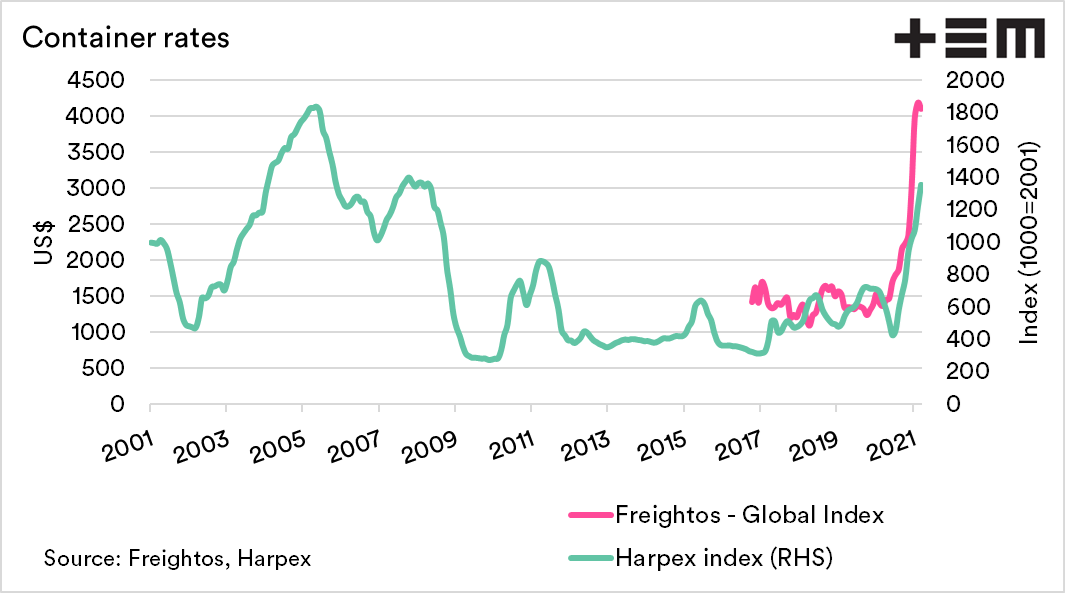

The chart below shows the Freightos global index, and the Harpex index provides a representation of container pricing. The Freightos has only been in existence since 2016, and Harpex since 2001.

They are both showing strong rises during the past year. In the case of the Harpex index, we see that levels have not quite reached the levels of the pre-GFC boom in global trade.

Where is the rise?

Prices are different around the world; we know that well when we examine grain prices (see here).

This is the same in container pricing. If we delve into the data behind the Freightos global index, we can look into specific routes.

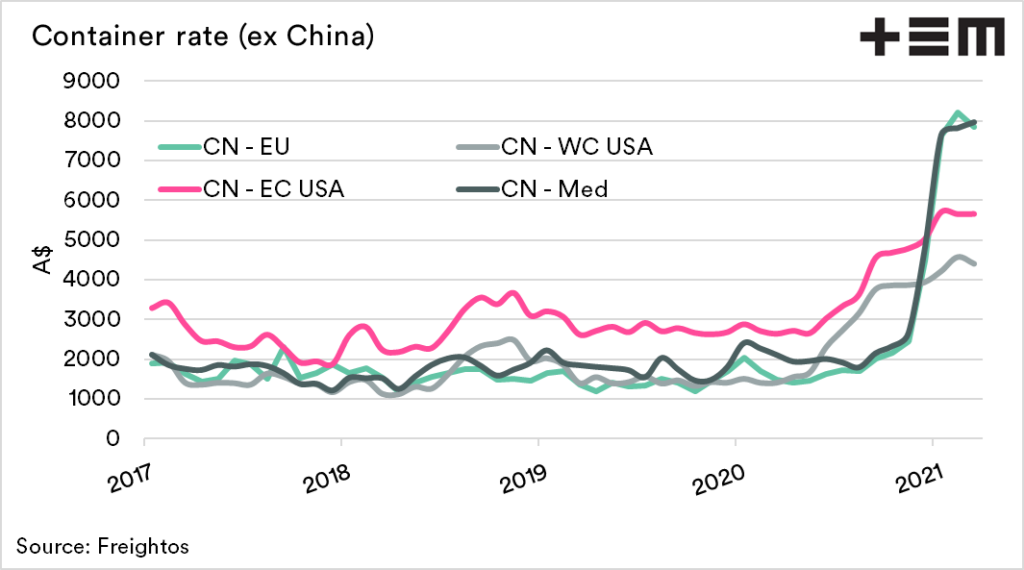

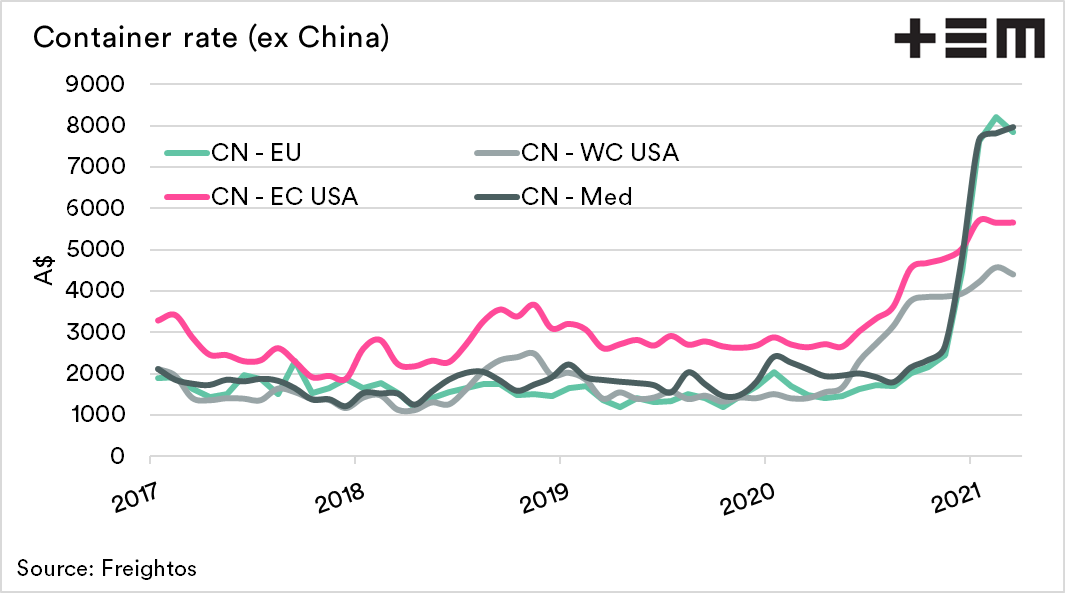

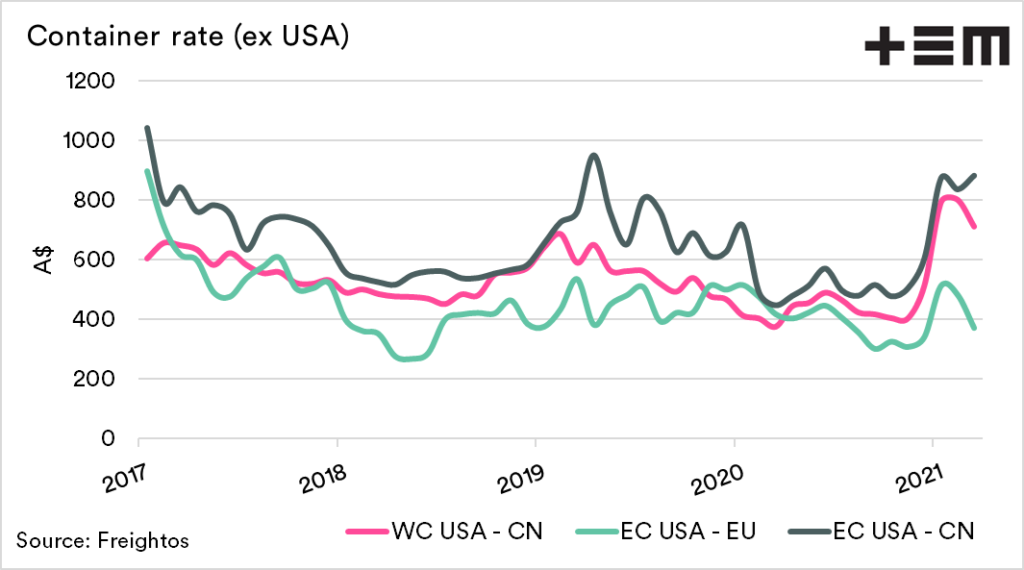

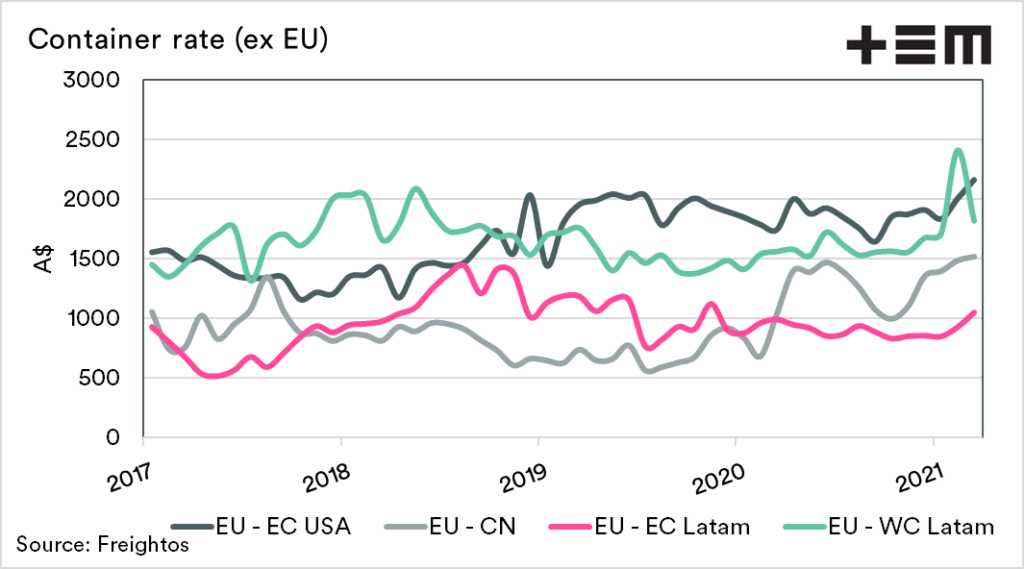

The three charts below display the container rates from three different origins, ex China, ex EU and ex USA.

The largest move in pricing has come from containers ex-China. A large proportion of gadgets and gizmos come out of China, and their economy has rebound quickly. The rest of the world hasn’t followed quite the same pace.

Also, containers heading back to China have been raising a premium. This is due to the demand to get containers back to a region where trade is moving intensely.

Full steam ahead

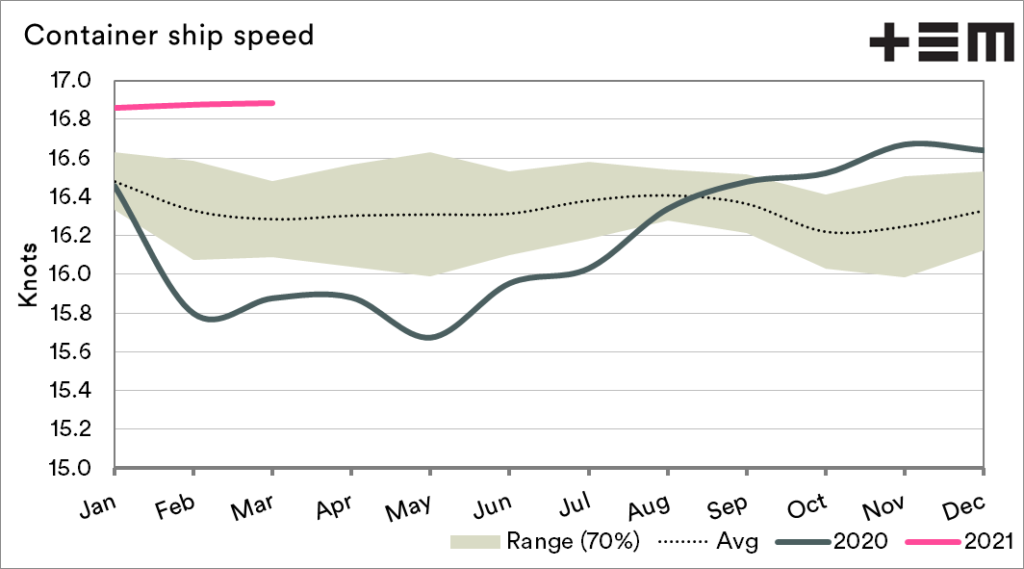

There is another indicator of and that is the speed of vessels. In recent months the average speed of container ships around the world has increased dramatically. During the depths of container prices last year, a container vessel’s average speed dropped to 15.6-15.8 knots.

The reason for ships to slow down during periods of low demand and pricing is to conserve fuel and reduce costs.

At present, container ships’ speed has increased in line with the cost of containers as shipowners attempt to get to the next port and unloaded/loaded as quickly as possible. So whilst containers are expensive, they’ll be moving quick.

What does this all mean?

Firstly it means that the logistics costs of moving items such as wool and smaller movements of grain/pulses. The majority of grains in Australia are exported on bulk vessels, so the impact on grains is likely to be minimal, and more focus on the bulk rates is required.

However, the cost of executing wool and meat is likely to be increased. As most of our wool goes to China, and then after processing to Europe, this will be felt. At the same time, large quantities of meat will go in refrigerated containers to parts of Asia, and the cost of freight will weigh heavy. It is important to note however that freight costs from other origins will also be similarly increased.

Will it continue forever? I was working in the import of animal feed into the UK during the period 2004-2010. I went through the rise in shipping costs during the commodity boom. During that period, the rise was unprecedented, and many thought it would never to end.

This lead many to commission new vessels, which were left unutilised for years in the post GFC period. I’d say that this is more an issue of vessel and logistics positioning, causing spikes in the China route. The relatively average rates evidence this in other routes eg EU to USA